Monarch

.

Monarch Articles

| Monarch: Grand County's City of Atlantis |

Monarch: Grand County's City of Atlantis

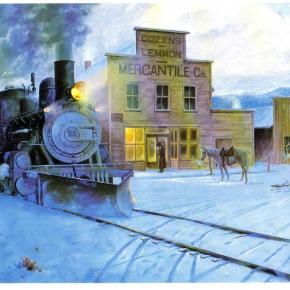

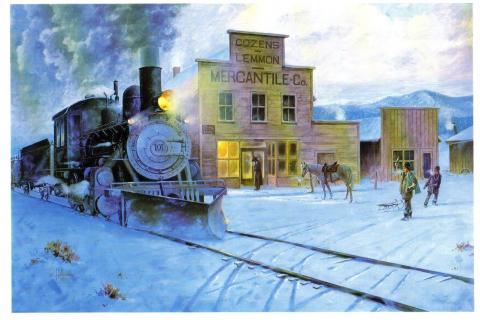

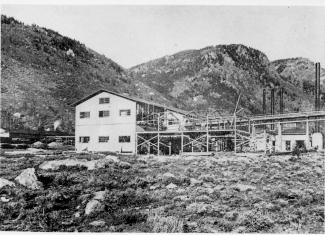

Monarch, now a picturesque lake for meandering around on a pleasant summer day, was once a bustling town, the home of the Monarch Consolidated Gold and Copper Mining and Smelting Company, and the rail head of the Rocky Mountain Railroad. The life of this little company town and railroad was very short lived and now nearly forgotten. Boulder business men T.S. Waltemeyer, and Frank and Charles A. Wolcott heard about traces of gold, silver, and mostly copper at the junction of the Arapahoe Creek and the South Fork of the Colorado River. In 1905 they established the Monarch Consolidated Gold and Copper Mining and Smelting Company and built their company on the assumption that a major belt of minerals extended east through the Continental Divide. The Monarch Company consisted of several subsidiary companies including lumber companies, an "investment" company, an exploration company, and a development company. The main objective of the company was to mine metal ores, but supplement it with timber and build a railway to benefit the whole corporation. Finally Dick McQueary agreed to move the machinery. To accomplish the job, McQueary purchased several hundred feet of hardwood planks in Denver, 3 inch thick, sixteen inches wide and twelve feet long. Accompanying the heavy pieces up the mountain was a "4 horse team hauling hardwood plank, a 4 horse team pulling six inch pine poles, 10 feet long, and a four horse team pulling two ton large nails". The crew built temporary bridges across mud-holes by laying pine poles 3 feet apart with hardwood planks laid across the poles. 2 light loads were driven across to test bridge followed by the heavy load pulled by 12 head horses. Finally the planks and poles were pulled up to be used at the next mud-hole. The heavy machinery was hauled in 2 weeks. Once the railway was completed and in operation it issued passenger tickets. However, the company never published a schedule. Neither did the company hire a full train crew to run their single locomotive. To meet regulations for switching service on Moffat tracks in Granby, the Rocky Mountain Railroad took on board a couple of interested bystanders. At gates crossing ranch properties fireman Leo Algier would simply jump off the train to open the gate and close it after the train had crossed through before hopping back on the train. Ranching families on the line were allowed to catch rides on the train when it passed through or to request package drop-offs. The Monarch Company created Monarch Lake by damming the valley, at the junction of Arapahoe Creek and South fork of the Colorado River, for use with the saw mill and the box factory. A 2800 foot long chute carried tree trunks down the hillside to the lake where they hit the water and could bounce up to 50 ft high. Then a stern-wheel steamer pushed logs into a system of canals and flumes that led down to the saw mill and box factory. The town of Monarch included employee housing, business offices, a post office, and an assembly hall. Dick McQueary helped haul sawlogs to mill and haul materials for building employee housing in Monarch. Grand County's first hydro-electric generator was in Monarch. The waterworks system was created by piping water from the falls at Mad Creek and had pressure up to 300 lbs per inch. Even thought the mining company never produced more than $150 a year, the owners continued to promote the business to stockholders and they were able to keep the business running by through their enthusiasm for the project. During the summer, stockholders were invited to visit Monarch, tour the site, and hear lectures on the operation. The tour often included a visit to a spruce tree named "Monarch" that was seven feet in diameter. So, while business might not have been booming, enthusiasm and interest from stockholders was. The last piece of Monarch to be constructed was the box factory in 1907. Unfortunately the factory only operated for 2 or 3 months before it suffered a fire and was totally destroyed. Robert Black in Island in the Rockies stated that the questionable promotions of Monarch would have been forgiven if the box factory had developed into a solid operation. Soon after the fire, a disagreement between management and labor resulted in the entire work force being fired. For several months the Rocky Mountain Railroad operated the train with one man who acted as engineer, fireman, brakeman and conductor. The company hired Dick McQueary as general manager until fall the fall of 1907 when stockholders discovered the true state of the company and declared bankruptcy. Stockholders and the community were convinced that the whole company had been created as stock-selling scheme. Although the Monarch Company and the Rocky Mountain Railroad were no longer in business, the railway continued to be used for a number of years. For example, Ed McDonald, dude rancher, put a Cadillac touring car on flanged iron wheels to carry mail, supplies, and guests to his ranch. The center of town was preserved and developed by the Dierks as a summer resort called Ka Rose, after Katherine Rose Dierks, after the owner's daughter. In 1912 the rail line was used for transporting fisherman along the river by Ernest F. Behr, a former Colorado and Southern engineman. Finally, in 1918 the rails were sold to a junk dealer in Denver to satisfy the World War I need for scrap metal. Currently, the town, mill site, and box factory lay under the waters of Lake Granby and are inaccessible, except in years of draught. However, there are a couple of remaining pieces at Monarch Lake that are still visible. On the south side of the lake, near the water's edge, is a boiler that was used to yard logs into a chute and shoots the logs into a holding pond. Also, the flume still runs down the hillside into the lake. The trail around Monarch Lake takes hikers directly under the flume. |