Because Grand County has such a rich history, many names reflect that important heritage. Traveling East to West from town-to-town, here are a few historical tidbits to think about.

Winter Park came into being around 1923. Several names to identify the place were used over the years, including West Portal, Hideaway Park, Vasquez, Woodstock, and even "Little Chicago" because of gambling and other activities. The City of Denver bought land in 1939. Winter Park officially opened in 1940. According to "Colorado Place Names" by George R. Eichler, with the assistance of Denver Mayor, Benjamin F. Stapleton, the town changed its name to "Winter Park" to publicize the establishment of the city's winter sports centers.

Iron Horse Resort and Zephyr Mountain Lodge reflect the importance of the railroad in the development of Grand County. Newer condominiums also reflect the heritage of the area. Sawmill Station, Teller City and more recently, Telemark, are a few examples. "Telemark is named after the traditional method of skiing," said a Telemark Townhomes representative. Red Quill townhomes, according to broker and owner Mike Ray of Century 21 Real Estate in Winter Park, are named after President Eisenhower's favorite fishing fly lure. "He found the Red Quill pattern particularly effective on St. Louis Creek while visiting and fishing with Axel Neilsen at the Byers Peak Ranch." Van Anderson Drive, according to Jan Smith, a Realtor at Century 21 of Winter Park and longtime local, is named after the first mayor of Winter Park. He developed the Hideaway Village, including the condos, Filings 1 and 2 and Hideaway Village South.

Vasquez Road, according to well-known historian, Abbott Fay, is named after Louis Vasquez, an early fur trader. Woodspur and even Woodstock, one of the early names attributed to the town of Winter Park, referred to Billy Wood's lumber mill which furnished Rollins Pass railroad ties.

Fraser was originally spelled "Frazier" for Reuben Frazier, an early Grand County Settler. Postal authorities adopted the simpler spelling when the post office was established. Doc Susie Avenue is named for Susan Anderson, M.D. "Doc Susie," a pioneer physician who came to the area in 1907. She served the citizens of Grand County faithfully until she died in Fraser at the age of 90. Fraser's Eastom Avenue is named after George Eastom, who founded the town. The Eastom family from Ohio built an important lumber mill. Mill Avenue also reflects those early lumber days. Eisenhower Drive is named after President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who enjoyed visiting the area especially for fishing. Ptarmigan is a grouse with feathered feet particularly found in the cold, mountainous regions. And, for Wapiti Drive/Lane, Wapiti is an elk. Zerex Street, according to Susan Stone of the Fraser Visitor Center, is named after the antifreeze product which was tested at "the Icebox of the Nation."

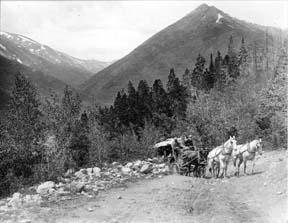

Tabernash is on the homestead of 1882 pioneer Edward J. Vulgamott. By 1905, the enclave came into existence because of its location during the building of the Denver & Salt Lake Railroad. E.A. Meredith, chief engineer, named the town after the Ute Native American called Tabernash who was killed earlier by a white man named "Big Frank." Junction Ranch, built by Quincy Adams Rollins, according to noted historian Abbott Fay, was an important stop on the Idlewild Stage line which could accommodate up to 50 travelers.

Granby was founded in 1905, named after attorney Granby Hillyer, who assisted David Moffat and Frontier Land and Investment Company with the incorporation. Granby landmark, Kaibab Park was donated by the Kaibab Company. According to former local postmistress Carole Clark, during the 1940s, Broderick Wood Products Company had a large sawmill with housing for their workers where the current ball fields are now located. Selak Drive is named after the Selak family, who ran a large Granby Merchantile. Before Granby, the Selak post office and general store provided service from June 1883 to September 1893 on the nearby Selak Ranch.

Ouray Ranch, a residential community located off US. Highway 34, was the original home of the YMCA Camp Chief Ouray until the early 1980s when the YMCA sold the land and relocated to Snow Mountain Ranch outside of Granby on US Highway 40. Chief of the Ute Indians, Ouray was born in Colorado in 1820. He was noted for his friendship with the white settlers.

Grand Lake was established by hardy pioneers in 1879. Joseph L. Wescott, was the first white settler-prospector. Grand Lake was founded as a mining settlement by the Grand Lake Town & Improvement Company. As the mines played out, tourism and focus on Grand Lake, Colorado's largest natural body of water, took center stage. Cairns Avenue, according to Jane Kemp, granddaughter of James Cairns, is named for him. In 1881, he ran a general store. He extended credit for supplies to many of the miners who left town without paying him. With unpaid bills and depleted stock, Cairns then homesteaded a ranch to sell hay to freighters for their horses. He trapped bears for their shaggy skins to sell. All the while he kept his store open. A mountain peak bears his name, also.

Columbine Lake is named after the Colorado State Flower. Kinnikinnick is a Native American term used to describe mixtures of Indian tobacco. West Portal Road leads to the west portal of the Alva B. Adams Tunnel, which since 1947 delivers Grand County-Western Slope water to farmers on the Front Range as part of the Colorado-Big Thompson Project.

Hot Sulphur Springs, established in 1860 is named for the famous hot springs in the area. (Colorado Place Names) Ute and Arapaho tribes used the hot springs for their "healing waters." Byers Avenue is named after William N. Byers, founder of the Denver Rocky Mountain News. He wanted to create a spa resort modeled after Saratoga in New York.

Moffat Avenue-Several streets in Grand County are named after David Moffat, the pioneer railroading legend, who started the Moffat tunnel and brought predictable rail service to Grand County with his "true-grit" determination.

Parshall, according to Colorado Place Names, was established in 1907 when a Mr. Dow set up a small store and circulated a petition for a post office. The name "Parshall" honored a local pioneer. Postal authorities accepted it as no other post office had that name in the entire county.

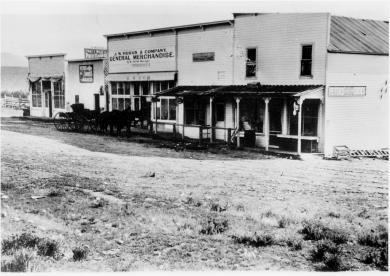

Kremmling established in 1881 according to Colorado Place Names, the town's beginning was a general merchandise store run by Kare Kremmling, (The Chamber of Commerce web site says Mr. Kremmling was named Rudolph and the town was established in 1884) located on a ranch on the north bank of the Muddy River. When Aaron and John Kinsey platted their ranch and called the site Kinsey City, Kremmling moved his store across the river to a new site which soon became known as "Kremmling."

Radium had a post office as early as 1906. Harry S. Porter, a prospector and miner, suggested the name because of the radium content in a mine he owned near the town. The community was settled by Tim Mugrage and his family.