True Crime

Every community has it's stories of the dark and shocking things that people sometimes do.

True Crime Articles

| Commissioner Shootings in Grand Lake |

Commissioner Shootings in Grand Lake

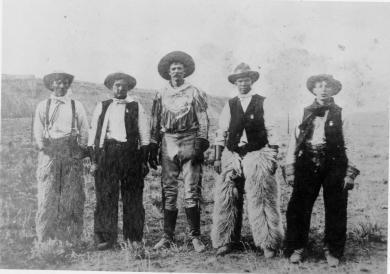

Article contributed by Abbott Fay & Steve Sumrall July 4, 1883 was a tragic day of unprecedented magnitude in the history of Grand County. The booming mine town of Grand Lake had managed to move the county seat from Hot Sulphur Springs a year earlier and there was growing animosity between the “lake” and “springs” residents. On that fateful day, County Commissioners Barney Day and Edward P. Weber, supporters of Hot Sulphur Springs as the County Seat, had breakfasted with County Clerk Thomas J. Dean. As the three left the hotel beside the lake, they were ambushed by four masked men. After the smoke cleared, it was determined that the perpetrators were John Mills (the 3rd County Commissioner), Sheriff Charles Royer, Undersheriff William Redman and his brother, Mann. Day died instantly, Weber died the next morning, and Dean died from infection on July 17th. But Day fired back back, killing one of the masked assailants, who later turned out to be Commissioner Mills. The other three escaped. The sheriff and undersheriff had quickly returned to Hot Sulphur Springs and shortly after, they were sent for to investigate the very crime they, themselves had committed! Sheriff Royer shot himself on the night of the 15th and his body was discovered the next day. Dean later testified that Mills shot Weber, Redman shot Dean, Day shot Mills and Readman and Royer shot Day. Undersheriff Redman disappeared shortly thereafter, apparently shot. A body was found later on the Utah border thought to be Redman but there was no positive ID. The body was suspected to be Redman from the size of his feet. Whether he killed himself or was murdered was never determined, but nonetheless, if it was Redman, he was the sixth victim of the Grand Lake Commissioner shoot-out. It is interesting to note that all three commissioners killed had been appointed to office rather than elected. Ironically, the county seat was moved back to Hot Sulphur Springs several years later. Sources: |

| Good Eye Bill and the Deadly Feud |

Good Eye Bill and the Deadly Feud

Article Contributed by Fran Cassidy The Depression of the 1930's had its effect all over the In the afternoon of The three visitors left and headed for the nearby forest and Good Eye asked The loggers returned to the cabin and noticed that Good Eye had a bloody arm. He described what had happened and pointed to the body. Penna suggested they take Good Eye to town and advise the Sheriff. An area sheep rancher, William Foley, was passing by with his flock and saw Sources: The Inquest reports

|

| Granby Rampage |

Granby Rampage

On June 4th, 2004 an armored D-9 Caterpillar was used by disgruntled Granby businessman Marv Heemeyer in a rampage that caused an estimated $5 million in damage and left part of the town of Granby in rubble. Heemeyer's slow-moving, 90 minute demolition, fueled by his anger at local officials and business owners who supported construction of a cement batch plant, left 13 buildings demolished or damaged and ended when he committed suicide inside the cab that he had welded shut. The buildings targeted included the town hall, the library, the electric company, a bank, the newspaper and the home of the former mayor. The town of Granby was spared any human injuries or loss because of the complete evacuation of the town through the reverse 911 system and many local law enforcement officers who went door to door to warn the townspeople. The town of Granby immediately launched fundraising efforts to offset the losses suffered by targeted businesses and citizens and the destroyed buildings were mostly rebuilt by the following year. |

| Kremmling Bank Robbery |

Kremmling Bank Robbery

Article contributed by Robert Peterson and Elsie Fletcher Ruske The summer of 1933 offered more excitement than usual. First there was a lost child who kept most of the Fraser Valley busy searching for several days. Just two days later, the town of Kremmling was visited by two criminals who came to rob the local bank.

|

| Spider House Tragedy |

Spider House Tragedy

Nestled on a quiet lane in Old Grand Lake City sits the intricately crafted home of Warren C. and Mary O’Brien Gregg, known today as the Spider House – a testament to a remarkable woodcraftsman and his tormented wife. Warren (Watt to his friends) was a dreamer and in the 1870s he left his first wife and a young son in Wisconsin and headed for the Colorado Territory seeking his fortune in the mines of Gilpin County. Upon returning to Wisconsin his first wife died of fever, leaving Warren a widower with a small son. Holding tight to his dreams of the west, Warren eventually ended up in his native Indiana where he met and married 20 year-old Mary O’Brien, in 1884. By 1888 Warren packed his new family into a prairie schooner and headed west. Like so many other pioneer women before her, Mary bore a child along the trail, a second son whose short life would send Mary down a dark and tortured path. The family arrived in Middle Park late in the summer of 1888, built a small homestead on the eastern slope of the Stillwater drainage and the newborn died shortly thereafter. Though the years would bring more children, Mary would never quite recover from the loss of her second son. They continued to scratch out a living in this harsh and isolated land, where winters were long and supplies were meager. Warren spent much of his time searching for game and exploring this new country. The Gregg’s moved numerous times, finally purchasing a plot of land from Old Judge Wescott on the west side of the lake. Warren built his family an admirable house, with intricate detail and spider-like webs of wooden elements. Despite the warmth and comfort of this new home, and the close proximity of neighbors, Mary’s depression deepened. Then on a sunny Sunday in 1904, while Warren was working in his woodshop and oldest son Lloyd was having Sunday dinner at Judge Westcott’s, Mary took a gun to her four remaining children and then turned the weapon on herself. The children died instantly while Mary lingered on for four days. The five victims of this tragedy, one girl, three boys and Mary herself are buried together in one grave in the Grand Lake Cemetery. Warren lived in the Spider House for another 29 years. With his son Lloyd, he continued building homes and stone fireplaces. He succumbed to heart failure in 1933. Mary O’Brien Gregg finally found peace in the quiet grace of the little town cemetery surrounded by her children. Almost a century later, as the tall pines whisper their mournful winter song, the Spider House still sits nestled on that quiet little lane. |

| Sudden Death in Old Arrow |

Sudden Death in Old Arrow

A shooting in the Old West I know was not much like the shootings on television today. There was no glorification of the bad man. Killings were usually like the fatal shooting of Indian Tom on that 6th of September, 1906, in old Arrowhead (or Arrow). Nobody called anybody out. Nobody told anybody to draw or asked him if he was wearing a gun. It wasn’t a fight. It was a killing. 1906 Arrow had six saloons, a grocery store, one small hotel and a livery stable. But two thousand people picked up their mail there. The woods were full of tie-hacks: the three sawmills hired may lumberjacks and teamsters, most of them Swedes, who seemed to make the best lumbermen. I had arrived in Arrow the 18th of April that year to work as a teamster for my brother Virgil, who had been operating a sawmill there for about a year. I was just sixteen. My brother Dick, the tallest Lininger, had been Virgil’s foreman. Virgil had also bought the only hotel in Arrow. My mother, two sisters and my little brother Gilbert and I came from our farm in Osawatomie, Kansas, so that my mother could run the hotel. My brother Wesley came at that time too: he planned to buy a lot and build a café. Whole families often followed the first member who had come to these early Colorado towns. I soon discovered that driving logging horses needed a lot more technique than driving a small farm team, but Virgil was patient, and I soon received a raise to $2.75 a day as top teamster. The town was a wide open as it could get. My first introduction to the violence was the day my brother Dick fired three drunken lumberjacks. They drew their pay and went to Graham’s saloon to get drunker. As dick passed the saloon later, one of the men grabbed a quart whiskey bottle, and ran out and struck Dick behind the ear, knocking him cold. The three then proceeded to kick him around. Dick’s roommate Charley came to my brother’s rescue. When Dick came to, he started for the hotel. Charley guessed what he was after and beat him to the six-shooter. “I’ll make sure you can taken them one at a time” Charley promised him. I came along just as my brother knocked the pick from the pick handle. Something was up! In less time than it takes to tell it, Dick had three drunks out cold. Mother patched Dick up. I think this was her introduction, too. A man couldn’t stay boss long if stayed whipped. Every other Sunday was a holiday for me although I always saw to it that I put in enough overtime to bring my monthly paycheck to $75. That September Sunday I was dressed in my holiday garb – tan peg-top dress corduroys, light blue wool shirt, Western hat, and high-laces boots as befitting a teamster who drove four or six horses hauling logs from timber country to the saw mill. When I drove six horses, I rode one of the wheel-team horses and held the lines over four. If I drove four horses, I rode the wagon and sat on a sack of hay. About noon, I stopped in front of the MacDonald saloon to talk to Ed MacDonald, one of the few saloon men my mother didn’t disapprove of. After all, Ed had come to Colorado as a TB and couldn’t do heavy work; filling glasses over a bar was about the only light work in those old mountain towns. Later Ed owned the famous MacDonald Ranch on the South Fork of the Grand Rover – now Colorado River- and managed boats on Monarch Lake just above his ranch. He always served great dinners and good food. While Ed and I were talking, Indian Tom rode up. He was a flashy cowboy of the old school, a very good looking man with predominantly Indian features although he was only half Cherokee. When riding, Tom always wore leather chaps, spurs, and a big Stetson. As wagon foreman for Orman and Crook, contractors for building the Moffat Road, he was a very important figure, for he had charge of all their wagons and teamsters. The greeting between Ed and Tom was cordial. Everyone liked Indian Tom. When Tom learned I was a teamster for my brother Virgil, Tom showed a much keener interest and invited me in to MacDonald’s for a drink. Ed rescued me. “Oh the kids doesn’t drink; but he might like a cigar”. As they ordered drinks, I puffed away in my best imitation of a Kentucky colonel; however I soon excused myself, saying that I had to target my 30-30 rifle for the upcoming deer season. I puffed until I was out of sight. The corn silk I had scorched behind the barn paid off. I didn’t disgrace myself, nor had I broken my pledge to my mother not to gamble, use profanity, drink, or perform any act inconsistent with the conduct of a gentleman. I took my rifle northwest of Arrow to Fawn Creek. It was a beautiful fall day. The aspen were just beginning to turn. Fawn Creek Gulch had been burned over many years before by the Indians who hoped in this way to discourage settlers, and the aspen were all young, straight and shimmering in the way that has never ceased to delight me. The fire thirty years before had made the gulch an excellent place for deer hunting because the new growth gave the deer some inviting protection, but the terrain was open enough for a hunter to locate his game. I figured I’d have to shoot from at least 200 yards, so I planned to target for that distance. I tacked a piece of cardboard I’d cut from my brother’s Stetson hat box (he never took off his Stetson off anyway) to a tree and stepped off the 200 yards. That 6-inch target looked pretty small but after each three shots, I’d examine the target. Finally satisfied, I took a long walk looking for deer sign, tracks, or droppings. I found good sign but no droppings. About feeding time for the horses, I went back to the barn in town to feed the four, Cap, the big bay, Bird, the glossy black (those were my two wheel horses- t e ones next to the wheel); Kate, the little lead horse; and Bud, her mate. Virgil had bought Kate, a grey mare weighing about 1400 pounds, at a very reasonable price from the Adams Express Company because she had run away at every opportunity and had destroyed several wagons. He couldn’t run away now pulling Cap, Bird and a load of lumber with her, but her high spirits made her an excellent leader. The heavier team, always used as the wheel team, weighed about 1700 pounds each. I was very proud of this unusually fine team. Virgil had trained Cap and Bird so that after they were harnessed in the barn, they could be turned loose to go to the watering trough, drink long and thirstily, then walk out to the wagon, back into position by the tongue, and stand ready to have the breast straps snapped in place and the tongue attached. When tourists trains stopped and hundreds of passengers stood around the eating places looking the town over, I’d drive slowly by, and then stop to rest the team a minute, to give the dudes a chance to see a good, four-horse team. Then with a single “Yup!” I’d pull all the lines tight, and they’d start as one horse while the tourists explained and pointed. That Sunday after I put a gallon of oats in their food box and shook some hay into their manger, I left the barn and started up the steps alongside the depot. It was still light; the sky hadn’t even begun to color. Time to head home for supper. I’d have to be up, hitched and pulled by seven the next morning. We’d probably have roast beef or roast chicken with noodles, since it was Sunday. Mother would be cooking on the big wood-burning stove at the hotel, and my sisters would be taking the heaping platters to the tables where everyone would pass them around. Probably there would be hot biscuits. Suddenly a shot cracked just above me and across the street. I knew instantly it had come from the Wolf Saloon ahead. It wasn’t common to hear shots in those days. You hear more in a 20-minute Western on TV than you heard in a couple of years unless a few boys rode into town on a Saturday night to shoot up the air. I broke into a run and could see a man lying on the board walk in front of the saloon. As I got to him, one of the ladies I wasn’t permitted to mention came out and fell to her knees beside him. Raising the man’s head, she tried to pour whiskey down his throat. With a queer, paralyzed feeling, I realized it was Indian Tom. I reached for his wrist. His hand was warm as life, but there was no pulse. Several men ran our. “Ragland got him!” one of them shouted. We carried Tom’s body into MacDonald’s and laid him on a roulette table that was in the back room for repair. Somebody went to wire for the sheriff at Hot Sulphur Springs. Word soon reached Orman and Crook’s, and the Indian’s many friends began to jam into Arrow. Indian Tom and Ragland had evidently had words during the afternoon and had quarrels once more before at a rodeo. The women from the saloon said that when Indian Tom left after the quarrel, Ragland had stationed himself, gun in hand, inside the saloon door. Everyone agreed that Ragland knew he wouldn’t have had a chance in a fair fight with Tom. The moment they heard Tom’s spurs outside , Ragland pushed the door slightly open and shot point blank through the aperture along the hinge. The he ran out the back door. We searched the town inside and out for Ragland. The sheriff joined is in the search late that night, but we found no trace of him. Just after midnight a wire came for the sheriff. Ragland had turned himself in at Hot Sulphur. We learned later he had run to a ranch down below, borrowed a horse and ridden for his life. A coroner’s jury was called. My brother Virgil, named foreman, took a firm stand. The only verdict he intended to take out of that room was murder, and, after only a few hours, that was their verdict. After three days, Ragland was released on $3,000 bond posted by his father, but you may be sure he didn’t show himself around Arrow. His attorney, John A. DeWeese, got a change of venue from Grand County to Jefferson County at Golden, claiming an article in the Middle Park Times of September 7, 1906, reporting the verdict of the coroner’s jury, made it impossible for Ragland to get a fair trial in Hot Sulphur. The article said in part: Four witnesses for the prosecution, and seven for the Defendant were examined, making eleven in all. The testimony of the witnesses on both sides failed to show that the shooting was justifiable. According to the testimony, the fatal shot was fired when Reynolds (Tom) had his revolver in his scabbard and when he did not even see Ragland who was standing opposite the cut-off. (As told to Donna Geyer by A.W. Lininger) |

| The End of Texas Charlie |

The End of Texas Charlie

Article contributed by Abbott Fay Charles Wilson, a punk nineteen year old, came to One day in early December, 1883 the gang invaded a saloon in Hot Sulphur Springs and threatened the life of the barkeeper, then went to a general store and pistol-whipped a randomly chosen customer. Threatened with arrest, Charlie challenged the local constable by tearing up the warrant. The hoodlums left town but chose to return on December 9th. They dismounted at the Justice of the Peace office and drew their pistols. Suddenly, Charlie's revolver was shot out of his right hand and his buddies pulled back. When the kid from A post-mortem investigation was held and everyone admitted hearing gunfire and seeing the body, but no one knew which of the "leading citizens" of the town had fired. The jury returned the verdict: "We find that said C.W. Wilson came to his own death by gunshot wounds at the hands of some person or persons to us unknown". His partners had left town and were never seen again in Hot Sulphur Springs. The kid from Source: Robert C. Black,

|

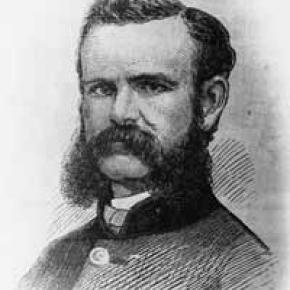

| The face of the 1883 Grand Lake Commissioner Shooting |

The face of the 1883 Grand Lake Commissioner Shooting

By Amy Ackman Project Archaeologist - 2018 I work in Cultural Resource Management (CRM), which means I document any man-made occurrence that is 50 years or older. I’ve recorded anything from prehistoric stone tools to 1940’s cans and glass. As a CRM archaeologist, I’m a data collector. Our job is to protect the archaeological record by gathering data and determining the significance of it. In 2011, I worked on a project near Jensen, Utah, just across the border from Colorado. During this project, I came across an unmarked grave. There was a headstone, but no name. I eventually found from historical documentation that the grave was that of a man named William Redman. Redman was the undersheriff who took part in the Grand County Shooting of 1883 that involved three county commissioners, a county clerk, and the sheriff. Three men died during the shootout, two men died of their injuries after the fact, and the sheriff committed suicide out of guilt. Two weeks after the incident, Redman was the only living participant. He was on the run from the law and actively hunted by the Rocky Mountain Detective Association. A full month after the shootout, Redman was found dead in Utah at the side of a road with a bullet in his head. I knew Redman was part of the Grand County Shooting and poured over any sources I could get my hands on; books, websites, newspaper articles; any tidbits of information that might answer questions. Like a detective, I wanted to understand how Bill Redman was involved in the gunfight and how he ended up in Utah. I found the story and a picture of William Redman and I was ecstatic that a site I had recorded was associated with such a tale. William Redman was ruggedly handsome with high cheek bones and pronounced jaw; the clothes and countenance of a miner. The more I learned about him, the more questions I had. How old was he when the photo was taken? At a time when it was such a privilege to have a photo taken, why is there a photo of him and not other prominent men in the county? I wondered about his motivations. Was he the ruffian newspaper articles touted him to be? Archaeology is about understanding the past. Most of the time we are forced to interpret the past with only a few pieces of material that are left behind. The more material and data we have, the more we can understand. In the case of William Redman, there are questions surrounding his death that give rise to the possibility that the man in the grave is not Redman at all. If the opportunity arises to excavate the grave, his photograph will assist in his identification. Archaeology not only studies the past but works to preserve the past for the future. Now, I hope that a family member of yours is never being researched by an archaeologist for being a ruffian and a murderer. But, like an archaeologist, I would encourage you to preserve as much as possible for those in the future who would care to learn about the past. |

| The Selak Hanging |

The Selak Hanging

Fred Selak was a descendant of early settlers in Grand County. He built a cabin three miles south of Grand Lake where he lived alone. He helped his brothers in various enterprises including mining, a general store and a sawmill. Selak was known to be a prosperous citizen who lent money to others and there were rumors of hidden cash and gold in his cabin. He was also known to be an avid coin collector. When Selak failed to pick up his mail for several weeks, the postmaster visited his cabin July 26, 1926. After not getting a response to his knocks, the postmaster summoned an employee of Selak's with a key. When they opened the door, they discovered the cabin in shambles and Selak missing. Sheriff Mark Fletcher was notified and a nephew of Selak's called in the Denver Police Department. As the investigation progressed, a .22 caliber slug was extracted from the wall and blood was found on an easy chair, but further investigation ruled these clues inconsequential as they were dated to many years prior. Sheriff Fletcher conducted a massive manhunt on August 16th and the body of Fred Selak was found on the second day by a deputy's dog. The body was hanging from a tree and evidence showed that, because of a sloppy knot, Selak did not die quickly of a broken neck but rather suffered a slow strangulation. The murder had taken place a month earlier and the body had stretched until the feet were touching the ground. Arthur Osborn, 22, and his cousin Roy Noakes, 21, became prime suspects after showing off old coins and trying to spend them for minor purchases around Grand Lake. After interrogation by the Denver Police, both confessed to robbing and killing Selak. Later, Noakes claimed that the confessions were coerced by the police. The suspects were kept in the Denver jail until their trial on March 7, 1927 and Sheriff Fletcher had to take great precautions against a possible lynching. The only motive for the murder seems to be based on a land dispute years earlier in which Osborn was arrested for a violating fence line. Both suspects were found guilty and sentenced to death. After many appeals, the convicted murderers were hung in Canon City on March 30, 1928. |