Health Care

Health Care Articles

| Doc Ceriani |

Doc Ceriani

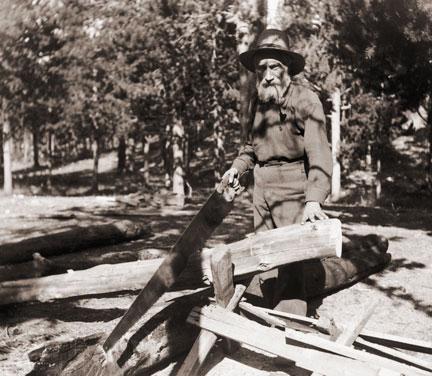

Article contributed by Kathy Zeigler Dr. Ernest Ceriani was a graduate of Loyola Medical School, and served his internship at St. Luke’s Hospital in Denver. In 1942, he married a nurse, Bernetha Anderson, and joined the Navy, serving until 1946. He began a surgery residency in Denver, but was unhappy with city life, city medical practice and its politics. He came to practice in Kremmling in 1947, working for the Middle Park Hospital Association. The Association had purchased the home of the previous doctor to remodel and serve as a hospital; it employed 2 nurses as well as the young doctor. The doctor was general practitioner, seeing patients in office, hospital, and home, often as far away as Grand Lake. He was as self-sufficient as he could be, developing his own X-ray films, for example, as a cost saving measure. Medical practice for an isolated doctor was challenging. Consultation with other physicians was difficult if not impossible and keeping up with medical journals was daunting. Source: |

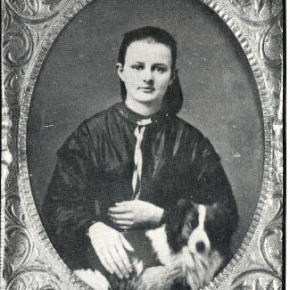

| Doc Susie - Mountain Pioneer Woman Doctor |

Doc Susie - Mountain Pioneer Woman Doctor

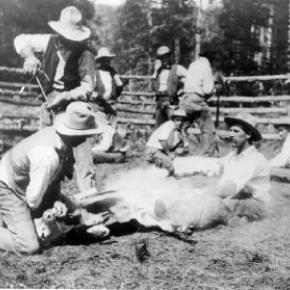

Susan Anderson was born on January 31, 1870, in Nevada Mills, Indiana. Her parents, William and Mary Anderson, were divorced in 1875. Four-year old Susan never forgot her parents arguing and her mother crying before her father literally grabbed Susan and her brother John, who was three years old, from their mother at a railroad depot. He jumped on the train as it was leaving the station and took them to Wichita, Kansas, where he homesteaded with Susan’s grandparents. Susan’s father, Pa Anderson, had always wanted to be a doctor, and he vowed that one of his children would fulfill that role, which he had been unable to accomplish. John, however, was more interested in roping cattle and playing than becoming a doctor. Contrary to John, Susie watched her father, a self-taught veterinarian, as he worked on animals. She absorbed important knowledge for her future as a physician. Susie was less interested in the lessons that her grandmother taught her: manners, housework, crocheting and cooking. Shortly after Susan and John graduated from High School in 1891, Pa Anderson remarried and became very domineering, insisting that everything be exactly as he demanded. At about the same time, the gold strike in Cripple Creek, Colorado, caught William Anderson’s attention, causing him to sell his homestead in Wichita and move the entire family to Anaconda, CO, which was about one mile south of Cripple Creek. Very rare for the time, Susan pursued an education in medicine and graduated from the University of Michigan and started practicing in the mining towns of the area. In her 30's Susan contracted tubuculosis and came to the Fraser Valley in hopes of a cure in the clear mountain air. Not only did she regain her health, but she he practiced medicine from 1909 to 1956 in Grand County, a total of forty-seven years. People in the area were very poor and seldom paid in cash. They usually gave her meals for payment. This suited her fine because she did not like to cook or keep house, which was always messy. Because the railroad ran beside her shack, she often would be called to various parts of the county, even at night. Doc. Susie would flag down a train and ride wher ever she needed to go, free of charge. She also treated the men working on the railroad and their families in Fraser and Tabernash, which was about three miles northwest of Fraser. Around 1926 Susan became the Coroner for Grand County. One time she hiked eight miles on snowshoes to a ranch because she was con cerned about a woman who was due to deliver her baby soon. That night the mother gave birth to a baby girl. While there, the four-year-old son had an appendicitis at- tack. Neither of the parents could take the boy to Denver for surgery. Doc Susie took him by train. A blizzard hit, blocking Corona Pass. The men passengers were called out to help clear the track It wasn't until the next morning the train arrived in Denver Doc Susie had no money for a taxi fare. The passengers gave her the taxi fare to get from the depot to Colorado General Hospital. Doc Susie stayed with the boy during the surgery from which he fully recovered. Another time Doc Susie rented a horse drawn sleigh to go as far as she could, then snow shoed into a ranch in a storm to treat a child with pneumonia. She had the rancher heat his home as warm as he could, heat water and then put the child in a tub of steaming hot water and open the door to make more steam. By morning the child had recovered. SDoc Susie lived to be ninety years old. The last two years of her life she was cared for in a rest home by the doctors for the Colorado General Hospital out of respect and love. Susie wanted to be buried beside her brother in Cripple Creek, but because of bad record keeping, no one could find his grave until later. She was buried in a new section of the cemetery. When the residents of Grand County learned there was no head stone, they took up a collection and erected a headstone. Susan Anderson never married, but she said she had delivered more children than any one and claimed them as her children. Her family was everyone in Grand County. Her home still stands in Fraser and the Cozens Ranch Museum has a display of her life and medical tools.

|

| Dr. Sudan |

Dr. Sudan

Article contributed by Barbara Mitchell The people of Grand County have been lucky to have good doctors from early times to the present. Such a one was Dr. Sudan.

|

| Health Care |

Health Care

In its earliest days of settlement, Middle Park area residents and travelers doctored themselves using whatever remedies they were able to concoct on the scene of accident, illness, or injury. The cure might have been a poultice of herbs, bread, oil, mustard, or something called Raleigh’s Ointment. It might have been a dip in the medicinal springs at Hot Sulphur, a dose of iodine, arnica or vinegar, castor oil, Epsom salts, or any number of other standbys. The first “doctors” known in the area were Dr. Hilery Harris (1874 or 1876) and Dr. David Bock (1876); both were “self-certified”. Dr. Harris had a predilection for the treatment of animals, while Dr. Bock treated the medical and dental needs of the people. By the mid-1880s, there were a number of doctors traveling through the area, working for various entities and setting up private practices. During the mining boom, there were a number of physicians and surgeons in Teller City, which was then a part of Grand County. Dr. Archie Sudan built a medical facility in Kremmling and Dr. Susan Anderson remodeled a barn in Fraser to accommodate her patients. Often it was the wife of the doctor, who might be a nurse, who attended the patients. Many of those in attendance were trained by the doctor in charge; some went on to attain certifications as Registered Nurses or other professionals. |