October 2009

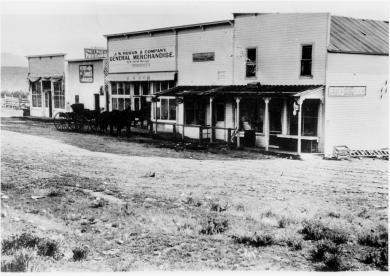

Here we have a story of two families, who became intertwined in a far away place where there weren't too many people. In fact, there was only a handful. Three young fellows, the Rundell boys, came from Wisconsin about 1880, to settle on the Sheephorn, an area in the very southwest corner of Grand County.

Al, the oldest brother, chose land on the Upper Sheephorn. While he was at it, he established a much-needed ferry across the Grand River at today's Rancho Del Rio. His brother Clarence homesteaded land on the same stream some two miles above the Midland Trail, known to us as the Trough Road. The only home he could afford for a couple of years was a dugout under the creek bank. That tended to be damp and dingy, but Clarence hung in. Finally he was able to build a cabin uphill from the stream. Newspapers used as insulation on his cabin walls show the year to be 1882. Clarence was pleased with his house. "Now I feel I've really put down roots and am here to stay!" he exclaimed.

Their young brother, Ernest, was frail, for he had suffered all his life from lung trouble. Still, he loved working with Clarence. One summer, they were digging a water ditch near Azure, on the Grand, above Radium; Ernest caught pneumonia and died. The poor boy was only about sixteen. Clarence never got over his brother's death and he gave land for a cemetery, where he buried Ernest, the first person there.

The second family were the Rundell boys' neighbors, Charlie French and his older brother, Harry, Jr. who had "hit town" from Iowa just about the same time. Harry homesteaded upstream from Clarence and anticipated ranching. By and by, though, Harry remarked to Charlie, "I've discovered I'm not much of a hand at ranching and besides, my land isn't very fertile. I think I'll sell it and become a U.S. Forest Ranger instead. If they'll have me." He easily passed the test and soon transferred to the little community of Azure.

Now, Charlie French was a wonderful musician, a whiz at playing the fiddle. He missed making music with their sister Phoebe. "You know, Harry," he said one day. "I'd really like Phoebe to come out and see this country. I'm sure she'd like it. And besides, we could play together again."

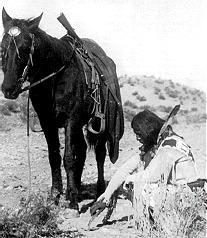

He urged her several times to come visit. At last she agreed, traveling by train to Leadville, then to Wolcott. About then, Charlie started to worry. "Phoebe's only 18," he thought, "and she's such a lady. Is it proper to expect her to ride sidesaddle all the way in from Wolcott?" He stopped by to see Clarence Rundell. "Clarence, do you suppose you could take your buggy to Wolcott and pick up our Phoebe?" He explained the circumstances. "Why, I'd be delighted," answered his friend.

It was a happy development. At the station Clarence saw a lovely young woman, tall and slender, obviously well-educated. He soon found she had a beautiful soprano voice and was an accomplished musician who could play both piano and organ. He took to Phoebe right away, and she, to him. It wasn't long before the two decided to marry.

Now the French boys' parents, Harry, Sr. and Mary, sold their Iowa farm about now and homesteaded at Azure, to be near their boys, even though Charlie left the country soon after. Here the old folks remained for many years. They also had some land up the Little Sheephorn, which they gave Phoebe as a dowry, when Clarence and Phoebe decided to wed. Shortly after, the happy young couple married and made the little cabin their home.

Their three children were born here, Ernest, named after the brother who died, Marie, and Helen. Clarence worked very hard, ranching in the summer and cutting logs in the winter. The young folks were thrifty. In 1908, Clarence sold his homestead to a Swiss newcomer and bought land above his original site. By 1912, Clarence and Phoebe built a fine three-story house, complete with beautiful hardwood floors. It was wonderful place to raise the children. "This will surely be our home forever!"

Harry French, Sr., died in 1924. "Mother," invited Phoebe, "move in with us, since you're alone now." Mary did this, but then she returned to Iowa to stay with her sister, until her death. The French name continues on, however, for there are two French Creeks in the Sheephorn area.

Finally, the Rundells decided to buy a home in north Denver and to invest in an apartment house. All went well until 1928, when everything fell apart at the beginning of the Depression. Clarence lost nearly everything. "Let's go back to the ranch, Phoebe," he said. "I still have my 300-400 head of cattle; I know ranching and love it. Let's go." Thus they left city life and returned to their ranching roots.