Transportation

How did people travel to Grand County? How did they get around? Click on the drop-down menus and take a little trip through history.

Transportation Articles

| Getting Around in North Park |

Getting Around in North Park

United States Geologist F.V. Hayden visited North Park briefly in August, 1868 in company of a small party of Army officers from Fort Saunders. The campsite he described on the Big Laramie River is where the Boswell Ranch was later established. They crossed the river at that point and entered North Park after following the Cherokee Trail twenty-five miles. The trail from Boswell angled across Beaver Creek and Bear Creek to Chimney Park and then turned southwest to the neck of the Park. It became North Park's main connection to the outside world. In 1879, the year of the great fires, naturalist George Grinnell hired a teamster with a stout team and a Studebaker wagon to take him to North Park from Laramie. By then wagon trails were numerous in the Park, probably created by market hunters who, in turn, likely followed travois-trails made by Indians. Stagecoach service between Laramie and North Park started in May, 1881 with tri-weekly trips by Concord coach to mining community of Teller City. The scheduled time for the trip was fifteen hours without any stoppage except for meals and to change horses. After the mining activity at Teller slowed down the stages ran from Laramie to Walden. Travel time was about twelve hours with three drivers on the route and five changes of horses, coming and going. The Laramie-Walden stage had the best record for continuous service of any in the west in 1907. At that time the mail had been carried six days each week for more than six years without missing a trip, although weather and roads had sometimes delayed the arrival of the stage until 2 or 3 in the morning. That is a remarkable record considering the weather conditions the stage traveled in. The editor of the Walden newspaper once described the Laramie Plains as a place "where the wind blows 400 days out of the year--sometimes with a speed and force that turns over wagons and miles of barbed wire fence." During the winter months the stage would typically start from Laramie with a coach with wheels, transfer to a coach with sled runners at a point above Boswell when the snow got deep, and then transfer back to a coach with wheels when the snow ran out in North Park. North Park had a public transportation system a century ago. From Walden local stages carried the mail to the various post offices scattered around the Park. Passengers could ride on the mail stages, so a traveler could get off the train in Laramie or Granby, take the stage to Walden and the next day catch a ride with the local mail stage to any place in the Park mail was delivered. During the winter months local travel was by team and sled, skis or snowshoes. Willow Creek Pass became an important travel route for North Park after the Moffat Railroad reached Hot Sulphur Springs in the fall of 1905. Dave Gresham established a road ranch for travelers near the top of the Pass. J.W. Welch, the Rand merchant, soon had two freight outfits running between Rand and Granby and tri-weekly stagecoach service between Walden and Granby started in the spring of 1908. Passengers left Walden at 6 a.m., spent the night at the Nixon cabins on Willow Creek Pass, and arrived in Granby at 11 a.m. the next morning. Wagon loads of oats from the Yampa Valley were freighted into the Park over Buffalo Pass. Construction of a road over Rabbit Ears Pass was still several years away. Cameron Pass was a major transportation route in the days when Teller City was booming. By 1879 it was obvious that the Park would soon be settled and Fort Collins businessmen were urging that a road to North Park be built to secure the travel and trade of the region before a trade route developed through Laramie. A toll road was completed over Cameron Pass by 1881. There was a charge of $2 for each vehicle drawn by one horse, ox or mule passing through the toll gate at Rustic. A single span was $3 and any additional horses $1 each. Business was brisk for only a few years and the road was opened to free public travel in 1902, but by then the public was using the road over Ute Pass and the road over Cameron Pass soon fell into a state of disrepair. While a few automobiles ventured into North Park each summer, there is no mention in the early newspapers of anyone in North Park owning one of the contraptions by the spring of 1909. There was one steam tractor in the Park and bicycles were popular. |

| Moffat Road |

Moffat Road

"I shall never forget it as long as I live. Nor do I ever expect to experience anything comparable to it again. Civilization had found its way across the mountains into Middle Park," reflected Mrs. Josephine Button in 1955 on her 91st birthday, as she recalled seeing smoke from the first Denver Northwestern and Pacific work-train on Rollins Pass, high above the Fraser Valley and Middle Park. Once those rails made it over the Continental Divide all the way to Hot Sulphur Springs, "changes came thick and fast." Many men, many dollars, many routes and many dreams tried to bring a railroad over the Continental Divide into Northwest Colorado, and the "Hill Route" over Rollins Pass that finally accomplished it a century ago has retained its allure ever since. The Moffat Railroad built a cafeteria, telegraph station, living quarters for Moffat's "Hill Men" (as the railroad crews up there were known) and a fine hotel - all collectively called Corona Station. Soot-filled snow sheds protected over a mile of this windblown section of track. And where today silence is the most powerful sense, colorful locomotives pulled passenger and freight cars, filling the rare atmosphere with black smoke and mechanical clatter. Decades of men's dreams lay behind the once massive snow shed that cut the bitter winds from the north and west, behind that fine hotel that offered some of the most spectacular scenery in America, behind the hopeful Town of Arrow nestled below tree-line ten or twelve miles west of Rollins Pass, and behind that first work-train that Josephine Button watched from her hay ranch along the Cottonwood Pass Wagon Road to Hot Sulphur Springs. Competent, often powerful, men in the 1860's through the 1890's filed surveys, graded road beds, and even began drilling before being stopped by severe storms that foiled the best laid plans or their inability to fund the ambitious projects. Dreams to penetrate the high mountains along the Divide in central Colorado began when the Front Range was flooded with miners during the Gold Rush of 1859. Even before Colorado became a territory in 1861, Golden City, just west of Denver along Clear Creek, recognized its potential as a gateway to the rich mineral resources of mountain towns like Central City, Black Hawk, and Georgetown. Golden City's ambitions went beyond becoming a mountain transportation hub, believing that with the right incentives, enthusiasms, and leadership, its location supported a future as a national commerce center. Golden City certainly had men of vision, ambition, and wealth among its ranks. William Loveland and George Vest, both young and feverishly ambitious to see Golden City reach its potential, vigorously pursued their dreams for a powerful commercial center in Golden City. From Missouri River towns like Leavenworth in Eastern Kansas, leading town founders also recognized the benefits of linking their water and rail routes to the east with the resources of the west. Finally, as if destiny had demanded it, Edward L. Berthoud, a young civil engineer and surveyor with energy and ability, arrived in Golden City from Leavenworth in April of 1860 to unite the similar passions of leading citizens from both locations. From 1861 until 1866, Berthoud, Loveland and Vest focused on bringing a direct transcontinental railroad route through Golden City. First, Edward Berthoud, along with Jim Bridger and a capable young cartographer named Redwood Fisher, blazed a trail across Berthoud Pass through Middle Park all the way to Salt Lake City. Returning to Golden City on May 28, 1861, Berthoud reported "a good wagon road could be ?quickly' built" from Denver to Salt Lake City over Berthoud Pass for about $100,000.00. According to the local hyperbole, a railroad would surely follow. In spite of considerable enthusiasm, disappointment plagued early efforts to put a rail line over the mountains in Colorado Territory. In 1862, Territorial Governor John Evans sent the Surveyor General for Colorado and Territories along Berthoud's route and others to confirm or deny the potential of a railroad line. About the same time, the Union Pacific Railroad Company sent an independent reconnaissance to examine potential routes over the divide that included Berthoud and Boulder Passes (Boulder Pass became Rollins Pass in the early 1870's, when John Quincy Adams Rollins built a toll road over it, and then Corona Pass when the Railroad crossed it). Surveyor General Case and the UP agreed that neither route offered much hope for a standard gauge railroad. The dream of a transcontinental line over the Continental Divide through central Colorado seemed to die with the UP surveyor's words, "I learned enough to satisfy myself that no railroad would - at least in our day - cross the mountains south of the Cache la Poudre..." Multiple failed attempts to bring a rail line over the Divide through Middle Park during the following decades strengthened the UP's "death sentence." Against the odds, Berthoud and Loveland continued to solicit support for a railroad west over or through the Continental Divide, using improved surveys and maps to support their requests. In the 1880's, survey crews from a variety of railway incorporations were scattered over the high country on or near Rollins Pass. Over Berthoud, Rollins and other passes, they marked potential railroad lines with their wooden stakes. It was during this stretch of strenuous surveying activity that David Moffat, a highly successful Denver capitalist, got involved with an unsuccessful effort to bring through the mountains instead of over the top. In the early 1880's, Mr. Moffat invested in the Denver, Utah and Pacific Railroad, which intended to tunnel through the mountains near Rollins Pass. Like the other efforts, though, the Denver, Utah and Pacific vanished in a few short years. Unlike many other lines that accomplished little more than surveys and maps, the DU&PRR completed significant grading and began tunneling before reaching the "end of its resources." Money, power and success supported Moffat's dream to put Denver on a direct transcontinental railroad line. Doctor Robert C. Black, III, wrote that David Moffat's failed efforts in the early 1880's converted him to the idea that Denver needed to be on a direct transcontinental rail line. Moffat considered the route over Rollins Pass valuable enough to have surveying and grading crews working on it throughout the winter in 1902. The Denver Rocky Mountain News claimed that Moffat's route through Northwestern Colorado included "the largest strip of fertile land as yet undeveloped in the United States..." With his Denver, Northwestern and Pacific Railroad, David Moffat planned to make good his intentions to put Denver on direct transcontinental railroad line. Moffat's original plan called for the "Hill Route" over Corona Pass ? the name changed from Rollins Pass in honor of Corona Station at the top ? to last for only a few short years. While the "temporary" route over the top generated resources by extracting the resources of Northwestern Colorado, a tunnel was to be bored through the Continental Divide. Even the wealth and power of Moffat, though, failed to adequately finance the tunnel before he died in 1911. The temporary line, therefore, lasted for nearly of a quarter century, from 1904 until 1928. Its obstacles proved as enormous as the mountains it crossed. Work crews had to cease operations because of snow for most of April in 1920. The road was closed from late January until May in 1921. In December of 1924, engine number 210 busted "a main reservoir pipe," causing the train to fly down the hill out of control until it jumped the tracks and crashed into the valley below. Clearly, the Denver and Salt Lake Railroad, which took over Moffat's DNW&P after his death, needed a tunnel to replace the expensive effort over the "Devil's Backbone." As Denver and Salt Lake Locomotive Number 120 came through the tunnel in early 1928, it represented the culmination of a massive undertaking through wet, unstable rocks which required considerable engineering ingenuity and caused six deaths in a 1926 cave-in. It also took an enormous amount of coordination and effort to secure the necessary funding. Through local bond issues, private investors and other means, the project was completed. And through a connection at Dotsero, a railroad station less than 30 minutes west of Vail on I-70, freight and passengers could make a direct Pacific connection from Denver. Posthumously, David Moffat's dream became a reality. |

| Railroads |

Railroads

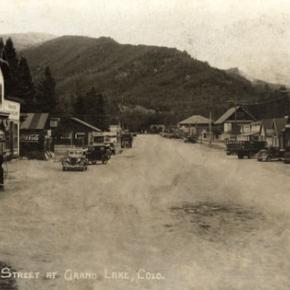

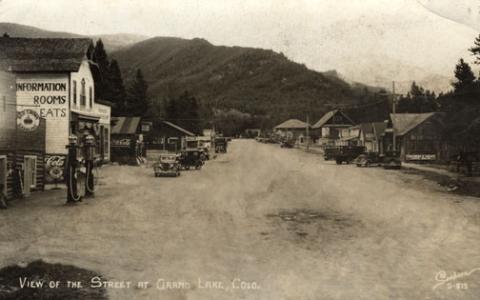

Construction on the railroad line from Denver to Grand County began in July 1902. The project, called the Moffat road (officially the Denver, Northwestern & Pacific), was the seemingly impossible dream of David H. Moffat, who spent much of his personal fortune building the tracks over the Continental Divide. The rails pushed higher and higher up the mountains until they reached a station named Corona, meaning the crown of the continent. Huge snowplows were required on either side of the Divide to keep the tracks clear. Eventually, in the late 1920s, a tunnel was dug through the range, eliminating 22.84 miles of track and the breathtaking journey over Rollins Pass. The railroad reached Granby and Hot Sulphur Springs in 1905 and Kremmling in 1906, and played a significant role in building the population of Grand County. In 1900 the total resident population of Grand County was only 741, but grew to 1,862 in 1910. |

| Stage and Freight Lines |

Stage and Freight Lines

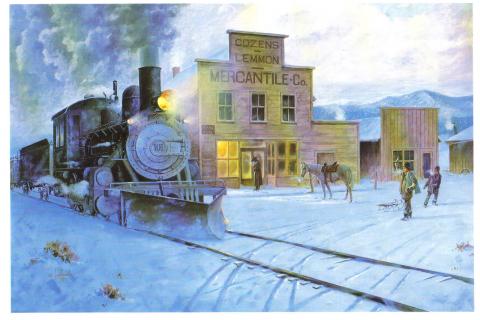

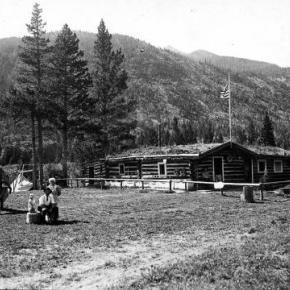

Berthoud Pass Stage Road was built by the extreme efforts of Captain Lewis Gaskill. It came from the top of the Pass through Spruce Lodge, Idlewild (now Winter Park), the Cozens Ranch (near Fraser) Junction Ranch (Tabernash) and Coulter. From there once branch lead over Cottonwood Divide to Hot Sulphur Springs (and points west) while the other went to Selak’s and over Coffey Divide to the Lehman Post Office and on to Grand Lake. At the summit of Berthoud Pass there was a large house of hewn logs, occupied by Lewis Gaskill and his family. They collected the tolls for the road and gave welcome shelter to those weathering the variable passage. The house was located on the West side of current Hwy. 40 but no trace of the building remains. At the steepest portion of the west side of Berthoud Pass was the Spruce House rest stop, which by 1900 was a sold structure of two and a half stories. There the traveler could find a warm meal and corral for livestock. No trace of it remains today. The Idlewild Stage Stop was located in present day Winter Park and was a popular place to change horses before the steep assent up the pass. Mrs. Ed Evans served a hearty noonday meal there for only 35 cents. Cozens Ranch was also one of the more popular stops and Fraser Post Office until 1904. Built around 1874 by William Zane Cozens, it remains today, outfitted in period décor and is the home of the Cozens Ranch History Museum. The Gaskill House, in Fraser was built by Lewis De Witt Clinton Gaskill, one of the original investors in the road and a prominent Grand County citizen. The house now houses the Hungry Bear Restaurant. Junction House at Junction Ranch (Tabernash) could accommodate up to fifty travelers and was built by Quincy Adams Rollins, and subsequently leased to Johnson Turner. The Coulter Stage Stop was built by John Coulter, an attorney from George town and shareholder in the stage road. It also served as a Post Office from 1884 to 1905. Frank and Fred Selak, sons of a pioneer Georgetown brewer ran the Selak stop which was north of Granby and east of current Hwy. 34. Cottonwood Divide (Pass), at 8904 feet above sea level, was laid out by Edward Berthoud and Redwood Fisher in 1861. The route was used by stagecoaches from 1874 until the railroad arrived at Hot Sulphur Springs in 1905. The last driver on the route was Charlie Purcell. Summer travel time between Hot Sulphur Springs and Georgetown was typically twelve hours. Travelers between Hot Sulphur Springs and Kremmling could stop at the Barney Day or King Ranches, both near current Hwy. 40. The Pinney Ranch House, used by the firm of Whipple and Metcalf for the connecting service to Steamboat Springs, is still standing on Hwy. 134 on the east slope of Gore Pass. There a traveler could pay 50 cents for a meal, 50 cents for a bed and expect a change of horses every ten miles. It ceased operation in 1908 when the railroad reached Toponas. |

| The flood that built the Moffat Tunnel |

The flood that built the Moffat Tunnel

Article contributed by Tim Nicklas For many years For In 1904, In the 1870s, much of By the early 20th century, The spring of 1921 started as many do in "All day long refugees, dazed, not knowing what to do, straggled about the streets. Mothers with babes in their arms, mothers whose arms were empty, old men and women and people of every description wandered about until gathered up and taken to Red Cross headquarters, where they were fed and allowed to rest." The scene in As The building of the Moffat Tunnel was an enormous undertaking that cost several lives and injured even more workers. Nonetheless, the tunnel from its inception has remained of vital importance to the |

| The Train Comes to Fraser |

The Train Comes to Fraser

Article contributed by Tim Nicklas A little over a hundred years ago the few residents of Fraser were awakened by a sound new to their town. The railroad had finally arrived in 1904, just over 30 years after it had first debuted in A hundred years ago, residents of the The reality of the chosen route for the D.N.&P. was due to grade and not fear of the rifle. Whether Cozens despised the railroad is anyone's guess. According to Robert Black's book, Island in the Rockies, the railroads designing engineers actually consulted Cozens concerning the lack of snow on the continental divide. Regardless, the rumors have persisted over the years about the "Old Sheriff's" contempt for the railroad. It has even divulged to me that the ghost of Billy Cozens will not allow anything concerning the railroad in his former home, the As far as the townfolk of Fraser were concerned, many of them regarded the railroad as an opportunity that had eluded the region for years. Unfortunately for Fraserites, their town was to be bypassed as the major hub for the area. Further down the valley Tabernash was chosen as the location for the workshops and roundhouse for the forthcoming trains. As a result, the trains would move through Fraser without their engineers paying the town much notice outside of their blowing whistles. Nonetheless, the people of the valley would embrace the iron horse. Economic potential in In years past, just like today, it has been easy to forget the benefits that the railroad has brought to our lives. Certainly, when the train moved into the valley, the people that day realized that their life could slow down a bit. The reality was that the short inconvenience that the passing train brought with its blaring horn, bringing traffic to a momentary standstill enhanced the life and character of the

|

| Train Legends of the Moffat Road |

Train Legends of the Moffat Road

Article contributed by Abbott Fay The railroaders graded and bridged the trails originally made by the Indians and expanded by the trappers, prospector and stage road builders that following in rapid succession. The In another lost train story, the No. 3 westbound was seven hours late out of Sources: Roland L. Ives, Folklore of Middle Park Colorado,Journal of American Folklore, Vol. XXXIV, Nos. 211, 212, 1941; Levette J. Davidson & Forrester Blake, Rocky Mountain Tales, University of Oklahoma Press, 1947

|

| Wagons of the West |

Wagons of the West

Transportation into Grand County in the late 1800's was one of the more difficult tasks. Stage coaches were used to carry the many people to and from the county. The first stagecoach into Grand County was a Concord. The Concord stagecoach was a luxury wagon weighing around 2,200 lbs. It cost around $1,050 and was beautifully painted. No two Concord luxury coach paint jobs were the same. The wheels were made of white oak and would not shrink in the cold or expand in hot weather, and made very reliable, durable wheels. The body was iron barred and was easier for the horses to pull than some of the other standard stagecoaches of its time. The mountain conditions caused different rules and a different coach then the stereotypical Concord. The inside of a Concord was four feet wide, and four and one half feet tall. The coach had leather curtains, but they did little to keep the dust, wind, snow, and rain out. Three benches lined the inside, and held nine passengers. The coach was often known to hold up to six people on the roof as well. Luggage was held in the "boot", a metal box on the back of the coach. Mail was often put in the "boot" for transportation, or kept right behind the driver. The average speed for the Concord was around fifteen miles an hour. The braking system was sand bags placed over the brake pads, so that sand could be released on rugged hills. The Concord was only used for one year because of its weight and bulkiness it did not make for a good coach in the mountains. The weight, price, and bulkiness caused this stagecoach to be produced for one year before another one came into play. At one third of the cost, the Dearborn took over after the Concord. These were known as Mud Wagons because of their easy travel in the mud and tricky terrain. The Mud Wagon weighed around 1,600 lbs. and was much more efficient. It had the standard four wheels, but was only pulled by one to two horses, and could hold around one to three people. However it was not as luxurious as the Concord. They often did not have side curtains, and the seats were not as nice. The cabin sat on wooden springs. The Mud Wagon was used by farmers, peddlers, emigrants, and pleasure travelers as it was affordable and decent in appearance. The weary traveler who took the stagecoaches soon learned the rules of the road. The best seat was next to the driver where there were less bumps. Never ride in cold weather with tight boots or shoes, or tight gloves. If one is asked to walk, do so without grumbling as the driver would not ask unless truly necessary. Don't jump from the moving wagon, as nine out of ten times you will get badly hurt. Do not drink alcohol in cold weather as it can cause hypothermia. In warm weather it is okay to drink as long as you are willing to share. Eat what is available, no one wants to hear you whine. Do not smoke, or spit on the leeward side. Never swear, and don't fall asleep on your neighbor. Do not ask how much longer, you will get there when you get there. Never fire a gun as it will scare the horses. Never grease your hair because of dust and most important - remember mountain traveling is hard.The first stagecoach into Grand County was a Concord. The Concord stagecoach was a luxury wagon weighing around 2,200 lbs. It cost around $1,050 and was beautifully painted. No two Concord luxury coach paint jobs were the same. The wheels were made of white oak and would not shrink in the cold or expand in hot weather, and made very reliable, durable wheels. The body was iron barred and was easier for the horses to pull than some of the other standard stagecoaches of its time. The mountain conditions caused different rules and a different coach then the stereotypical Concord. The inside of a Concord was four feet wide, and four and one half feet tall. The coach had leather curtains, but they did little to keep the dust, wind, snow, and rain out. Three benches lined the inside, and held nine passengers. The coach was often known to hold up to six people on the roof as well. Luggage was held in the "boot", a metal box on the back of the coach. Mail was often put in the "boot" for transportation, or kept right behind the driver. The average speed for the Concord was around fifteen miles an hour. The braking system was sand bags placed over the brake pads, so that sand could be released on rugged hills. The Concord was only used for one year because of its weight and bulkiness it did not make for a good coach in the mountains. The weight, price, and bulkiness caused this stagecoach to be produced for one year before another one came into play. At one third of the cost, the Dearborn took over after the Concord. These were known as Mud Wagons because of their easy travel in the mud and tricky terrain. The Mud Wagon weighed around 1,600 lbs. and was much more efficient. It had the standard four wheels, but was only pulled by one to two horses, and could hold around one to three people. However it was not as luxurious as the Concord. They often did not have side curtains, and the seats were not as nice. The cabin sat on wooden springs. The Mud Wagon was used by farmers, peddlers, emigrants, and pleasure travelers as it was affordable and decent in appearance. The weary traveler who took the stagecoaches soon learned the rules of the road. The best seat was next to the driver where there were less bumps. Never ride in cold weather with tight boots or shoes, or tight gloves. If one is asked to walk, do so without grumbling as the driver would not ask unless truly necessary. Don't jump from the moving wagon, as nine out of ten times you will get badly hurt. Do not drink alcohol in cold weather as it can cause hypothermia. In warm weather it is okay to drink as long as you are willing to share. Eat what is available, no one wants to hear you whine. Do not smoke, or spit on the leeward side. Never swear, and don't fall asleep on your neighbor. Do not ask how much longer, you will get there when you get there. Never fire a gun as it will scare the horses. Never grease your hair because of dust and most important - remember mountain traveling is hard. |