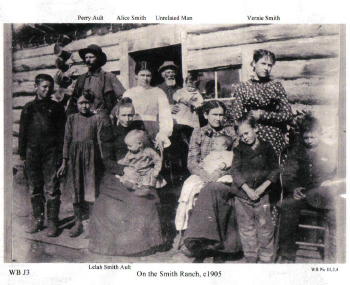

Lillian Russell Smith Wood was born in Dunlap, Kansas, in 1884, she was not a particularly healthy child. Born just before her and just after her were sets of twins, 2 of the 4 sets born to her parents and the only 2 sets that survived into adulthood. Lillian spent her adult years on the Williams Fork and then in Parshall. Known as “Gram” Wood to most everyone who knew her, she was grandmother to 39 who bear the names Wood, Noell, Stack, and Black. And her history in Grand County beginning in 1905 made her one of our pioneers.

In the fall of 1905, the local newspapers report that Herb Wood had lost a large portion of his right hand in an ore crusher accident. Herb had come into Summit County originally with a mule team for “Uncle Joe” Coberly, another Williams Fork resident and apparently worked in or around mines and mining equipment while also hauling the timbers for mine use. Herb needed some round the clock nursing, and in those days, for Gram to take proper care of him and still be in an acceptable position, they needed to be married. One source says the situation was so different that a Denver newspaper picked up the story with a headline of “Loses Three Fingers, Wins a Bride”, indicating that they married 3 days after they met. Research has never turned up a trace of that story, and it’s unlikely in the mining camps in the area that they hadn’t met until he was injured. Still, they were married by Judge Swisher, well known area businessman, in short order in the hotel room where Herb was recovering . A short time later they made a brief wedding trip to Denver and then returned to Argentine.

Before fall set in that year, the newly married couple moved to the Little Muddy. Herb had been sending money to a partner who was helping him to secure a homestead there not far from where Joe Coberly lived. It was probably with anticipation of a great future on their own land that sent them into Middle Park to face their first winter as a couple without having had a chance to raise a garden or preserve any winter supplies. They moved into one end of a two room cabin with a man named Ranger Charlie in the other. And about that same time, they discovered that Herb’s partner had been drinking the money he’d sent over the years. What devastation that must have caused!

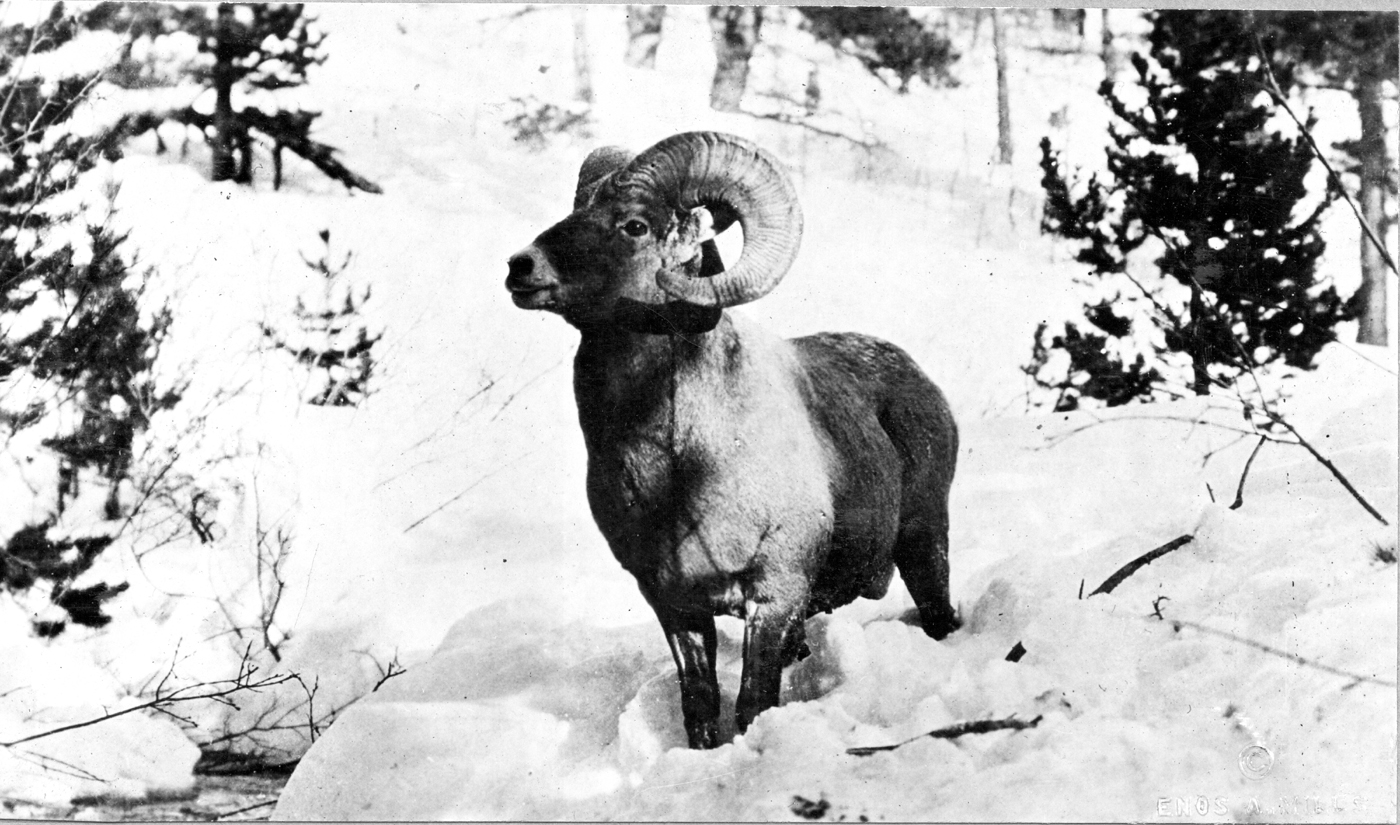

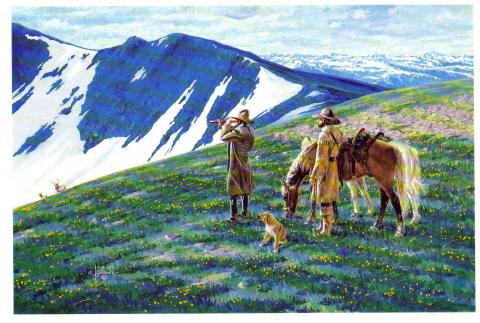

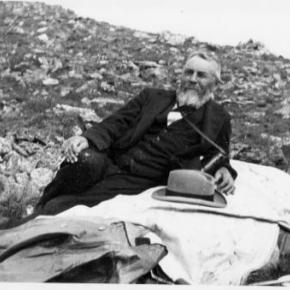

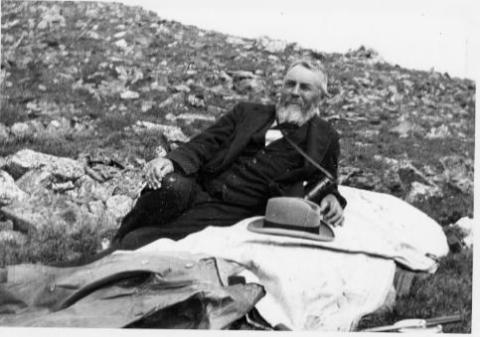

On the other side of the valley just across the creek was the large ranching operation known as the Hermosa Ranch, owned by Dr. T. F. DeWitt, a well-to-do doctor from back East. With the dream of his homestead gone, Herb went to work for DeWitt, eventually becoming one of his foremen. Gram probably helped out with cooking and cleaning, but within a few months, she went back to Kansas to await the birth of their first child. Over the next 21 years, she raised kids and gardens and developed her love of fishing, which helped feed a family that eventually totaled 13 kids, including a set of twins born 2 weeks before Christmas and delivered by Herb when a doctor couldn’t reach them in time. Pictures of the time show a large family of 9 boys and 4 girls with Gram, all 5’2” and maybe 100 pounds of her on one end, and Herb with a child or two on his lap at the other. The kids recall Christmases being supplied mostly by Mrs. DeWitt and sometimes being late if the trains got snowed out of the area. All attended one room schools, Hermosa and Columbine, and stories of their lives together can make one wonder why any of them survived.

Life continued pretty much routinely until 1928. That summer, the youngest daughter, Marilyn, a premature baby and ailing child caught whooping cough. She lingered and languished until early October, and then she passed away. The close-knit family had suffered it’s first loss. Two weeks later, Herb came in from the hayfield complaining of not feeling well. Gram followed him into the living room and sat down with him on the couch. Minutes later, he collapsed in her arms and died of a cerebral hemorrhage. They buried him alongside Marilyn in the Hot Sulphur Springs Cemetery.

The boys continued the work for Dr. DeWitt for several years, and in 1932, they built a 2 bedroom house for Gram several miles from where DeWitt had relocated his ranch. Her sons made sure she had what she needed as she finished raising the youngest ones who had been little more than toddlers when Herb died.

By the time I was old enough to remember much about Gram, she was already a “little old lady” who lived in a small, pink mobile home next to Uncle Kenneth in Parshall. Everyone knew that she was one of the best fishermen in the country, having caught as many as 1200 in a season when she was feeding her family by herself. She enjoyed creek fishing the most, and even as she got older her ability to maneuver around the biggest holes and catch fish in any small body of water never faltered. I never saw her get wet.

In the winter, she was totally unafraid getting a couple of her grandkids on a sled and making a run down the hill in Parshall that ended at the store and U.S. 40, which then went through the center of town. Had her feet not worked so well as brakes, we could have ended up on the pavement. But we never did.

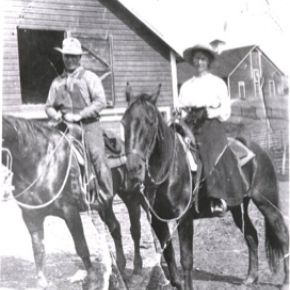

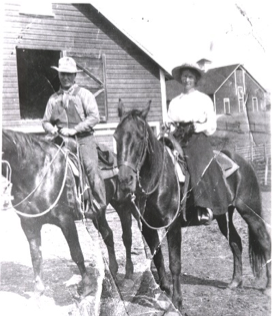

She must have driven many teams of horses in her day, and I believe she was a good rider. She never drove a car, but unless she needed to go to the doctor in Kremmling, she didn’t need to leave town. Her friends included Doc Ceriani’s mother and fellow fishermen from Hot Sulphur, a couple from Poland with heavy accents. Somehow, somewhere she had met Ralph Moody, author of the “Little Britches” series. And she, too, had a “fish” experience with warden Henry “Rooster” Wilson.

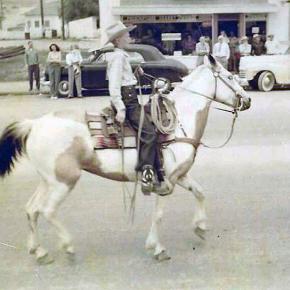

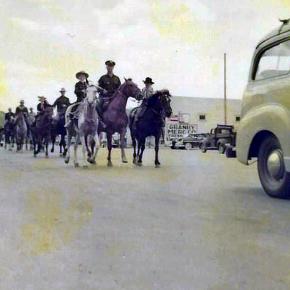

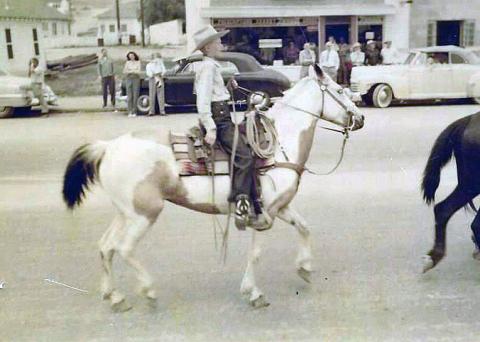

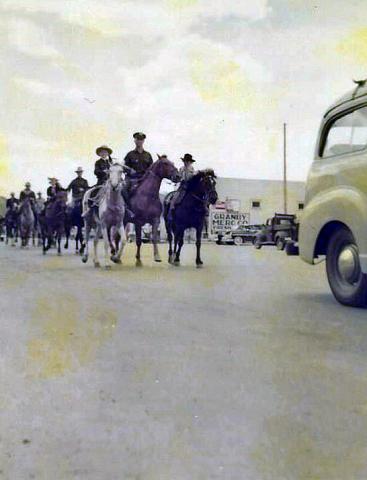

Only once did I get into trouble because of Gram. She was fishing one day near where I was getting ready to ride, when she laid down her pole and walked over to me. After watching me for a minute she said, “Can I ride?” What do you say to your 80 year old grandmother but, “Of course!” I saddled up the gentlest mare we had and helped her aboard. She only made a couple of trips around the small pasture, but as she rode, walking only, I’m sure I saw a young woman next to her husband on horseback in front of one of the Hermosa’s big barns. It’s one of the pictures you’ll find at the County Museum in Hot Sulphur. When dad found out what I’d done, he turned deathly white. “Don’t you know if she’d fallen or been thrown she could have been seriously injured or killed?” No, I had to admit. This was one rider’s request to another, with age no consideration . And to her at that particular moment, had either occurred I believe she would have considered those few moments worth the risk. When she was finished, she walked back to her fishing pole, satisfied that nowshe was done riding.

Gram introduced me to horehound candy, something I will also think about each time I taste it. And because she didn’t like my first name, I didn’t even know what it was until I started school. She taught me that barn cats do fish and that survival in a small living space was possible The one thing she didn’t teach me was anything about her growing up years or about my grandfather. It seemed like we knew as very young kids that we didn’t ask about him. I believe that hers was a love so strong that even to the point where her mind grew dim, the pain of losing him was too much to bear. One regret we all have, however, is that we never asked to her to go with us up to Summit County to show us where she lived and to tell us stories of that life and time. And unfortunately that’s been lost forever. Gram passed away in 1980, at the age of 97. She is buried with Marilyn and Herb and their son, Melvin who died during World War II in a family plot in Hot Sulphur with other family and pioneers characters nearby.

She left a true legacy through her kids and grandkids who continue the nostalgic traditions of their beloved Gram.

,

,

,

,  ,

,