People

People Articles

| Albina Holly King |

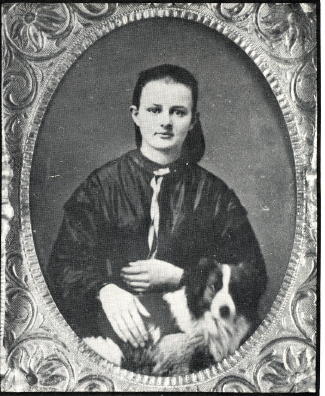

Albina Holly King

Upon the death of her husband, Henry J. King (1825-1879) who held the postmaster position for the Troublesome Post Office, Albina Holly King was appointed to the position in 1879 and held the position for 27th years. While it was said that she was the first woman Postmaster in the U.S., Postal records show that there were female postmasters back to the time of the Revolution. Albina’s daughter, Eva King Becker, also held the postal position and was listed as the Troublesome Postmaster in 1904, shortly before its closing. The original King homestead and post office is located behind the Welton Bumgarner home at the mouth of the Troublesome River. Henry and Albina came to Colorado from Ohio first settling in Empire, Colorado in about 1859-1860. Sometime after 1870, Henry arrived in Middle Park with Albina and their children arriving by the end of 1874. The Kings had five children; two sons Clifton G., Clinton A. (1852-1919) and three daughters, Aoela J. (born May 10, 1853 in Ohio and died September 28, 1858 in Michigan), Eva Marie and Minnie A. Both Henry and Albina were tailors by profession, however, their homestead became a trading post and lodging quarters for travelers. Water rights were important issues in the early Middle Park days, just as they are today. In 1882, Albina King became the first person to have claimed water. Tom Ennis claimed his water rights just 13 months later and claimed twice the amount as Albina. There were battles over their water rights, but Albina held her own. After retiring from the post office, Albina moved to Garfield County Colorado and lived with her son Clifton and his wife Lou (per 1910 census). By the 1920 census, she is living in Oakland, California with a granddaughter until her death in 1923 at the age of 98. Records indicate that Albina was cremated and her ashes supplied to the family, and possibly scattered at her beloved Troublesome wilderness. Thanks to David Green, husband of Susan King, direct decedent of the King family, for details provided for this article - July 2013

|

| Anna Bemrose Fetters Dietrich |

Anna Bemrose Fetters Dietrich

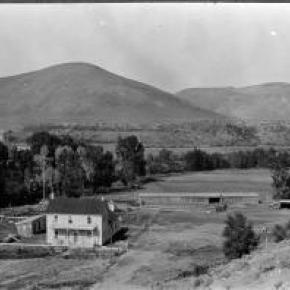

Anna Bemrose Fetters Dietrich married Jacob Dietrich in 1899 after the death of her husband John Fetters who had a neighboring ranch. Anna had six children; Jake, Lula and Winnie Fetters and Albert, Bertha and Horace Dietrich. Upon the death of Jacob Dietrich in 1910, Anna stayed on the ranch determined to build up a great cattle herd and educate her children who attended the Muddy School. In the 1920's, financial problems resulted in the loss of the cattle. However, in 1926 the "indomitable Anna" started over again, this time with sheep which roamed the ranch for 10 years. In 1935, Anna was forced to give up personal management of the ranch due to ill health. The Dietrich ranch was known as the "Lighthouse" for cattle roundups and Anna also hosted many parties and all-night dances for neighbors from near and far. Anna was quoted in the Times in 1939, " As on the big roundups, stopping places were scarce, my home was known by both the Middle Parkers and North Parkers." The last big roundup was in 1915 with a big Thanksgiving celebration a week late due to cattle gatherings. People stayed overnight in the bunkhouse and barn after lots of music and dancing entertainment. So ended a never-to-be forgotten roundup of the cowboys on the range! The range was then fenced by individual landowners bringing to an end the traditional roundups in the area. |

| Barger Gulch - Archaelogical site |

Barger Gulch - Archaelogical site

The prospect of discovering a remnant from a 10,000-year-old stone age society that inhabited Colorado's Middle Park so long ago seemed remote at best - while the suggestion that a prized Folsom point could somehow materialize before our very eyes appeared all but impossible. For one thing, it was the last day of excavating for the summer at the Barger Gulch archaeological site and the ten member scientific team would soon be packing up and heading back to their ivory towers at the University of Wyoming and the University of Arizona. Barger Gulch is a desolate spot that the federal Bureau of Land Management (BLM) oversees. It is hard, parched dirt dabbled with sagebrush as far as your eyes can see across the flat valley - a haven for all manner of bugs and other forms of native wildlife. In winter, the place turns to the opposite extreme as temperatures plunge to minus 40-degrees and howling winds whip up ghostly images of snow that swirl eerily across the land. This is Middle Park, a high mountain basin with roughly the same geo-political boundaries as Grand County. It encompasses some 1,100 square miles of unforgiving territory flanked on three sides by the formidable wall of the Continental Divide and its terrain soars high over the Great Plains into the thin, alpine air up to altitudes of 13,000 feet above sea level. What would induce these primitive Americans to trek all the way up here without so much as horses for transportation? How would they have survived the brutal winters with only primitive tools and clothing? And why in the world would they ever want to settle in such a barren, god-forsaken place as Barger Gulch? This site could well prove to be one of the most significant archaeological discoveries of its kind in North America, according to BLM officials who oversee the project here. In just three years of work in a relatively small excavation area, investigators unearthed more than 18,000 artifacts - a staggering number ten times that discovered at typical Folsom sites. And this is only one of four sites in the same vicinity. In addition to Barger Gulch and Upper Twin Mountain, discoveries include the Jerry Craig and Yarmony Pit House sites. Most of these were occupied by peoples described by archaeologists as Paleo-Indians, a catchall term for ancient humans that inhabited North America; Yarmony Pit House post dated Paleo-Indians by about 3,000 years. But long before Paleo-Indians ever set foot on the Continent, Middle Park was a prehistoric menagerie; 20-million years ago, it was the stomping grounds for prehistoric rhinoceros, three-toed horses, camels, giant beavers, and even small horses. Creatures known as oreodonts also romped across the mountainous terrain. These vegetarians, ranging in size from small dogs to large pigs, fed on grasses and green, leafy plants. In fact, the skull of one of these animals was discovered recently in the vicinity of Barger Gulch. These long extinct, hoofed animals resembled sheep, but were actually closer to camels, and were common in the western U.S. This latest discovery is remarkably well preserved; while the bones have turned to stone, the smooth, hard enamel that encased the animal's teeth is still intact. Humans arrived in North America much later - about 12,000 years ago - as the last Ice Age of the Pleistocene Epoch made its exit. These first Americans crossed a land bridge from Siberia to Alaska and began populating the entire Continent; experts believe it is possible they also arrived on boats following the Continental Shelf into North America. Folsom people are best known as nomadic, big game hunters who chiseled out their spear points and finished them off with a distinctive, artistic flourish - a unique groove, or flute, that runs lengthwise along the face that has become the symbol of this Paleo-Indian culture. They honed the tips of these primitive weapons surprisingly sharp for killing frenzies that were necessarily up close and personal: they herded their prey into traps before launching their spears - and archaeologists suspect there was just such a bison ambush site near Barger Gulch. The quarry just over the rise is a gold mine of raw materials, including fine-grained Kremmling chert and abundant Windy Ridge quartzite, which provided a never-ending supply of top grade stone. "It makes sense," explains Todd Surovell. "You would want to camp where you could get as many raw materials as possible within a short distance. That's where you're going to park yourself for awhile." The bulk of these tools originated with local material, but investigators have found some 200 "exotic" items noticeably out of place at Barger Gulch. One is a distinctive piece of yellow, petrified wood that came from 93 miles away as the crow flies, near the town of Castle Rock on the Colorado plains. Another is a large biface that was brought up from the Arkansas Valley, some 60 miles south. "They worked on it up here in one place and turned it into two, maybe three projectile points," notes Surovell. "One of them broke during manufacture and we have two pieces that fit exactly together." |

| Betty Cranmer |

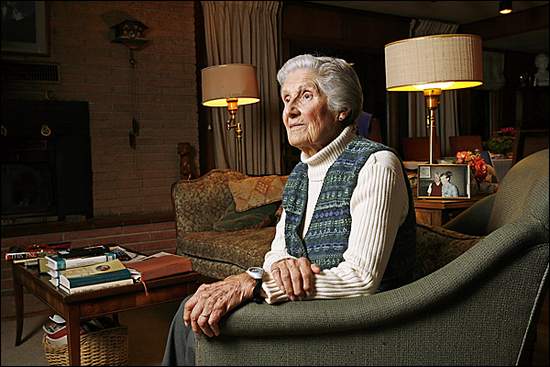

Betty Cranmer

November 2007 Betty Cranmer, a longtime She is a World War II veteran, a cancer-survivor, and the mother of five children (her sixth son, Forrest, died when he was 33.) She is the wife of the late Chappell Cranmer, whose father, George Cranmer, is the Cranmer the ski run at Winter Park Resort is named after. At 86 years old, Betty has lived a fuller life than many - and she shows no signs of slowing down.

Chappell, or "Chap," started a church in 1981 called St. Columba Chapel - later named Cranmer Chapel - that is located behind the Silver Screen Cinema in downtown |

| Bill Chenoweth |

Bill Chenoweth

William B. Chenoweth, age 87, died on January 17, 2005 and had a large impact on on the development of Grand County. The Chenoweth name was very familiar to Colorado residents, for Bill's father, J. Edgar of Trinidad, Colorado, served in Congress for 22 years, starting in 1940. Bill married M. Frances Gilbreath (d. 2011) and adopted two children with her, Glenn E. Chenowith and Judy Carol Chenoweth (d. 2015). Bill and his second wife Jean bought land and built a home at the top of Winter Park Highlands in the late 1960's; here, a whole new phase of his life developed. Bill ran for County Commissioner and Moffat Tunnel Commissioner. Chenoweth staunchly supported Grand County in his role as Tunnel Commissioner, for the Denver board members tended to want everything to align to their benefit. Chenoweth became County Commissioner at a time when the county was rapidly turning away from a ranching economy and becoming focused on recreation. It was a difficult period for many of the old-time citizens, in particular, but Bill's leadership helped to effect the change, which, of course, is now the standard. Bill's talent as a politician shone in his role as County Commissioner. He always said, "if you are going to be a politician, you need to like people and you need to remember names." At one County employee party, he stood up to greet the 100 guests, naming each person by name, each spouse, and except for one child, every child's name! Amazing! |

| Billy Cozens - First Settler in the Fraser Valley |

Billy Cozens - First Settler in the Fraser Valley

William Zane Cozens was born in Canada on July 2, 1830. After spending some time in New York, he moved to Central City Colorado in 1859, lured by the rumor of gold in the mountains. There, he became well known as a steady and trusted lawman. In December 1860 he married Mary York, who had been born in England in 1830. Mary was a devout Roman Catholic and was not happy with the uproarious mining camp of Central City and the constant threat to her husband in his role as Sheriff. So by the mid-1870's, they decided to relocate over the Continental Divide and established a hay ranch and stage stop in Middle Park (north of the present town of Winter Park). They had seven children, although only three ? Mary Elizabeth, Sarah Agnes and Willie ? survived infancy. Mr. Cozens became the Fraser postmaster in 1876, holding the position until his death in 1904. On July 29, 1878, there was a total eclipse of the sun over Colorado. The Ute leader Tabernash took that as a divine omen to take action against the increasing encroachment of white settlers, miners and hunters into Ute hunting grounds. Tabernash gathered 40 armed warriors and set out to attack the Cozens Ranch. Billy Cozens negotiated with the group, offered food and finally persuaded them to move on. The group ended up confronting another rancher and the face off resulted in the death of Tabernash (more details under Tabernash page). Mary worked very hard to make their isolated home a pleasant place. She even ordered dandelion seeds from a seed catalog in order to add color and zest to her garden. One can speculate that the source the abundant dandelions in the Valley are the result of Mary's original plants. The Cozens Families' stage stop became a well-known stopping place for summer tourists, who often enjoyed Mary's fine meals and "Uncle Billy's" (Mr. Cozens' nickname) tales from his days as a Gilpin County lawman. When Billy dies in 1904, none of his children had any offspring so Mary left the ranch to the Catholic Church and Regis University, which built a retreat on the property. In 1987 the ranch house was given to the Grand County Historical Association and now houses a museum. Source: |

| Chauncey Thomas: ‘Sage of the Rockies’ |

Chauncey Thomas: ‘Sage of the Rockies’

In 1900, while visiting in Washington, D.C., Chauncey Thomas, a nephew of William and Elizabeth Byers, wrote ‘Snow Story, or Why the Hot Sulphur Mail was Late’. When the great British author, Rudyard Kipling, read the piece, he pronounced it the ‘best short story by an American’. The opening paragraph of the ‘Snow Story’ reads as follows: ‘Berthoud Pass is a mighty pass. It is the crest of a solid wave of granite two miles high, just at timberline. Berthoud is a vertebra in the backbone of the continent. It is the gigantic aerial gateway to Middle Park, Colorado - - a park one-fifth as large as all England. The mail for this empire is carried by one man, my friend Mason.’ The story goes on to describe Mason’s winter trip over Berthoud Pass into Middle Park where he encountered extreme winter blizzard conditions, an avalanche and Salarado. Chauncey Thomas, a native son of Colorado Pioneers, was born in Denver in 1872 and died there in 1941. At the age of three, Chauncey suffered his first loss. ‘The light went out of my left eye forever. A pair of scissors did it’, he said. At age nine he received his first weapon, a .22 caliber revolver, and promptly shot himself in the foot. No matter. Forever after, firearms fascinated him. He attended Gilpin and East Denver High School where he was a military cadet, but except for military drill and mathematics, school interested him very little. After graduation and college attendance at Golden, Colorado and Lake Forest, Illinois, he found his way to New York City. Here, he worked as an editor for well-known magazines - McClure’s, Muncey Publications, and Outdoor Life (among others) and hobnobbed with the likes of Ida B. Tarbell, S. S. McClure, Jack London and Frederic Remington. He returned to his home town and occupied himself more and more with Denver’s historic past. On the night of September 23, 1941, in his garret room at 1340 Grant Street, he took up a scrap of paper and wrote: ‘stroke--agony’.The next morning a neighbor found him, pistol in hand, dead. Two years later, at Berthoud Pass on a mountain that bore his name, Chauncey Thomas was honored. Dr. LeRoy Hafen the Colorado State Historical Society’s historian and the Colorado Historical Society dedicated a monument to him on which was inscribed, Chauncey Thomas: Sage of the Rockies. Excerpts of this article are courtesy of Colorado Historical Society & Grand County Historical Association. The publication ‘Snow Story, or Why the Hot Sulphur Mail was Late’, written by Chauncey Thomas, is available in the History Stores at Cozen’s Ranch Museum and Pioneer Museum |

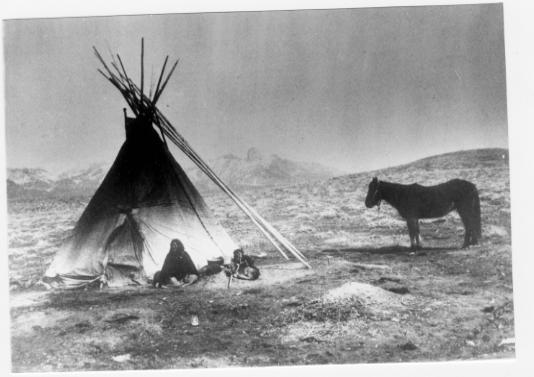

| Colorow - Ute Chieftain |

Colorow - Ute Chieftain

Colorow was a Ute Chieftain who was known for profound stubbornness and bitter resentment of the white man's intrusion into the Ute hunting grounds. Indian Agent Meeker had ruled that that the Utes must depend on the United States government for food supplies, rather than their traditional hunting. These supplies were sometimes held up for delivery and upon their eventual arrival,contaminated. Colorow thought the white settlers of Middle Park (near Granby) were killing too many of the game animals that had been critical in feeding the Ute people. So in the fall of 1878, Colorow started a brush fire high in the Medicine Bow range, planning to drive the deer, elk, and buffalo west to the Ute reservation. But the winds took an unexpected shift, driving the wild game northward and away from Ute territory. The fire drove out the last of the buffalo ever to be seen in the Middle Park region again and it took many years for the forests and ranges to recover from the devastation. |

| Crawford |

Crawford

Maggie and Jimmy Crawford came to Middle Park in the summer of 1874 with their three children. They were given a piece of property and built a one room sod roofed cabin in Hot Sulphur Springs. They were probably the first family to stay the winter in Middle Park. |

| David Moffat and the Railroad Dream |

David Moffat and the Railroad Dream

David Moffat was a wealthy Denver businessman who saw the need for a rail link between Denver and Salt Lake City. His vision, a 6.2 mile long tunnel beneath the Continental Divide, made this link possible. He was born in 1839, the youngest of 8 children. He ran away from home at age of 12, went to New York City and found work as a bank messenger. He was an assistant teller by the age of 16 and became a millionaire through real estate by the age of 21. Moffat was admired for his qualities of courage, adaptation to the “barbaric” West and his goodness of heart. He married his childhood sweetheart, Francis Buckhout, moved to Denver, and in 1860 opened a bookstore/stationary/drug store with C.C. & S.W. Woolworth on the corner of 11th and Larimer. Moffat and others formed the Denver Pacific Railroad to reach Cheyenne. The rail line to the Moffat Tunnel was the highest standard railroad ever built in the U.S. (11,660 ft). It went over the Continental Divide at Rollins Pass and came into the Fraser Valley in 1904. At the time, it was the most difficult railroad engineering and construction project ever undertaken. It involved boring numerous tunnels through solid granite, as well as constructing precarious timbered trestles that bridged deep mountain gorges. David Moffat was a multi-millionaire when he started the Moffat Line and was nearly broke when he died in 1911 trying to raise money for the tunnel that would eventually be built and bear his name. It was finally completed in 1928. The west portal of the Moffat Tunnel can be seen from the Winter Park Resort.

|

- 1 of 7

- next ›

,

,