* Copyright 2006.

No portion of this story or photos may be reproduced without the written permission of Gary or Sue Hodgson (www.hodsonmedia.com)

Early morning, mid January in Colorado's Middle Park is not for the faint of heart. It's forty below zero. Six inches of new snow have fallen over night, adding to the three feet that have been building since early November. Ranchers in the area don't even bother to look at the breath taking beauty of the Gore Range to the West as they trudge to the barn. Their minds are focused on hope the big diesel tractors will start. Snow has to be moved and cattle fed. Life in these parts revolves around "feeding". Soon, ranch yards will be full of diesel engines belching black smoke clouds. Up and down U.S. Highway 40, this scene is repeated on ranch after ranch ... except for one.

Just south of mile marker 169, a landmark rendered meaningless by snow much taller than the signpost, sets the Davison Ranch. Several hundred cattle wait semi-patiently to be fed in the surrounding meadows, yet there are no black smoke clouds or clattering engines. One might think the ranch deserted were it not for muffled sounds creeping through the huge log walls of the old tin roofed barn. Inside, a crew of five are performing a morning ritual that began in late November and will be repeated, regardless of the weather, seven days a week until mid May. Mark, Molly, Dolly, Nip and Tuck are getting ready to feed.

A crew this small is rather unusual for a ranch that encompasses over 6,000 acres. More notable, only one member is a man. The other four are horses, big, stout, work hardened draft horses. Standing on the wooden planked floor, side by side, surrounded by logs a man could hardly put his arms around, are four beautiful black and white Spotted Draft Horses. While not rare, the National Spotted Draft Horse Association celebrated it's tenth anniversary in 2005, the spotted giants are not a common sight. It is fitting such unusual horses would be found on this ranch. The big black and whites fit right into a program in place nearly fifty years. Mark Davison relates the Davison Ranch history as he harnesses the big "Spots."

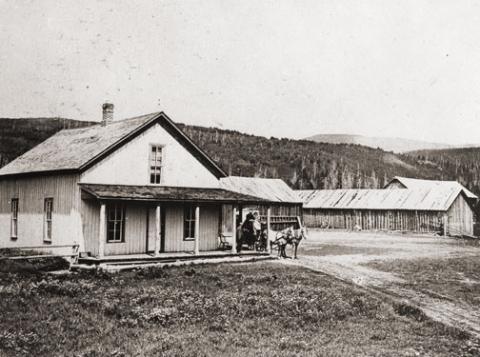

Mark's father, Charles Edward "Tommy" Davison, had been saving to buy a ranch since he was six years old. When the old place north of Kremmling came up for sale, the young bachelor fulfilled his life long dream. Tommy made a few observations. The ranch did not produce gasoline for the old tractors that came with the ranch. It did grow grass to power the two long ignored draft horses, also included. Then, there was the snow to deal with. It seemed easier for horses to pull a sled full of hay on top of the snow than trying to drive a tractor through it. The ranch was strewn with old harness and equipment including an ancient hay sled and various hitch components. He was single with an old house to spend the winter nights in. Why not spend a little more time outside with the animals he so loved.

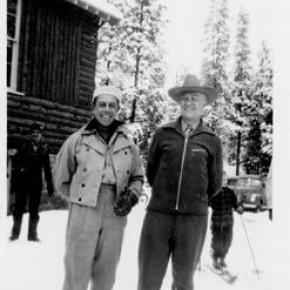

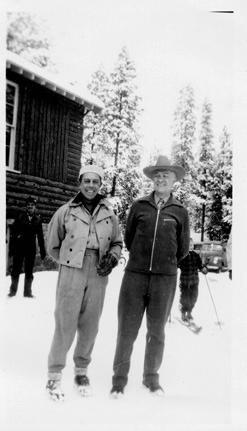

Not all of Tommy's plans went according to schedule. The hay laddened sled required more horsepower than his two horses. Two more "kinda" draft horses joined them. The old log house burned to the ground in December that first year. Hurriedly, he built a small cabin to live in until another house could be constructed. In 1958 he met and married Laurayne Brown. The Kremmling native beauty was used to the harsh winters and loved the big horses. Tommy and Laurayne made as good a team as Nip and Beauty, one of the better teams they would own in those days. As the ranch grew they realized they needed more help. New Year's Day 1960 they interviewed a likely prospect. Jerry Nauta sat at the Davison kitchen table as they talked. Finally, he uttered memorable words. "If you treat me right," he said, "I will never leave this ranch." Addressing Laurayne he went on, "I will probably eat more meals at this dinner table than you will."

Although the ranch owned several tractors as much work as possible was done with the horses. The ranch's hay crop, wonderful sweet smelling Meadow Brome, Timothy and Red Top was put into giant loose hay stacks. No need for big gas guzzling tractors pulling expensive balers on this ranch. A few other ranches also kept draft horses in those days. A big attraction at Kremmling's Middle Park Fair was the draft horse pull. Ranchers from neighboring North Park descended on the event with their horses, toughened by a summer of harvesting the Park's huge hay meadows. Most years they returned to their home valley with the Middle Park trophy. Tommy decided enough was enough. Even though he had never competed before, his team of the skittish Nip and gentle Beauty who scarcely knew a day out of harness, left the "invaders from the north" in their dust. The trio returned several more years, winning every single time. Finally, a bad referee's call moved another team into first place. Tommy, Nip and Beauty never entered again. It wasn't necessary. They had proven their point.

During those years, money would sometimes be so tight the loyal employee Jerry couldn't be paid. Tommy would sign a promissory note to him for wages. He was always repaid, with interest. Tommy told friends, "Jerry is my banker!" Jerry became a third parent to the three boys born to Tommy and Laurayne, Matt, Mark and Cal. They joined the early morning harnessing ritual, standing on a milk stool to reach the big horses under this watchful eye. When their father suffered a broken leg followed by a ruptured appendix, the boys, averaging ten years old, stepped into rolls as hired men. They calved cows, lambed the ewes in residence on the ranch in those years and, of course, harnessed and drove the teams to feed. If harnessing and driving a four horse hitch wasn't enough of a challenge, the feeding process creates men as tough as the animals pulling the heavy sled. Up to three tons of long stemmed loose hay have to be pitched onto the sled. Once the feed grounds were reached, every single blade is forked onto the ground as the patient team slowly moves ahead of the hungry cattle. Most days three or more loads were required to complete the task.

Tommy Davison fell ill in 2000. Mark who had remained involved in ranch operations while establishing another ranch in Wyoming, returned to the Kremmling ranch full time to oversee operations there. When Charles Edward Davison passed away in 2001, Mark leased the ranch from his family. Just as his father had done nearly fifty years ago, Mark took stock of what he had to work with. The harness, some nearly 100 years old purchased here and there over the years was in pretty good shape. The horses, however, had grown too old to be worked every day. He needed two more to complete his four horse hitch. Harley Troyer?s well known Colorado Draft Horse and Equipment Auction was coming up in Brighton, Colorado. Mark traveled to the "flat lands" and returned with two roan Belgium geldings. Sadly, one died within a year. He tried a "unicorn hitch" placing a single lead in front of the wheel team. It was not practical for the loads and trails they encountered. Mark headed back to Troyer's Auction once again. A novelty of the upcoming event was a pair of black and white Spotted Draft horses originating from Canada. When he arrived at the auction Davison found not two, but four of the Spots, two geldings and two mares. All were only two years old. To most, the big youngsters would need years of seasoning before they would be dependable. A lifetime spent around draft horses gave Mark Davison a different view.. He noticed how much time previous owners seemed to have spent with them. It showed in their responsiveness and manners. Auction owner Troyer remembers them as "A nice four up." When his gavel fell, all four were headed to Kremmling.

Today, as nearly every day of the year, the wheel team of Nip on the left and Tuck to the right of the wooden tongue, follow the lead team of Molly and Dolly, left and right respectively. They begin pulling when Mark softly commands "gitup" and stop when told to "whoa-a." Armed with an antique True Temper three tine pitch fork (this model is no longer made according to Mark) he hardly notices their direction as he pitches hay to the trailing cattle. The scene is spell binding to anyone fortunate enough to see it. Soft commands, creaking leather and steel clad wooden sled runners gliding over the snow summon long forgotten instincts.

Though Mark describes himself as a "Dinosaur," all that happens on the Davison Ranch is part of a plan that arose from necessity. He points out that when hitched to the sled, only the wheel team is attached to the tongue. The lead team's evener, an antique itself, is attached to a log chain r nning back to the front of the sled, not attached to the tongue in anyway. Tight corners the team must navigate winding into the mountains to feed the cow herd make a conventional arrangement dangerous. If the wheel team follows the lead teams tracks too closely, the sled would cut the corner and plunge off the precarious road. The loose chain arrangement allows both sets of horses freedom to follow their own path. The horses, sensing their safety as the reason for the odd arrangement, work quietly beside the chain. If one happens to step over it, the next step will be back into place without so much as a twitch of an ear.

Feeding begins around 8:00 a.m. The teams are usually back in their stalls eating "lunch" by 2:00 p.m. Six hours, eight tons of hay and nearly ten miles every single day make the horses tough and strong. They symbolize the word that describes life on the Davison Ranch. Harmony. The horses work in harmony with each other and their care taker. Horses and man work in harmony with nature. There is a strong respect for tradition on the Davison Ranch. The old ways made sense then and now. There is no need for electric engine heaters or big diesel engines on this ranch. The beautiful black and white horses seem to be thankful for the chance to live the life for which they were bred. They express their gratitude with loyalty to Mark Davison.

Loyalty might also be used to describe the Davison Ranch business plan. Remember Jerry Nauta's pledge to never leave the ranch if they treated him right? Jerry lived in the small cabin Tommy Davison built when the ranch house burned down from January 1, 1960 until a few months before his death in July 2005. He was 92 years old.

Life is different on the Davison Ranch. Old fashioned values reign amidst modern Spotted versions of man's first and perhaps best machinery, the draft horse. Men and horses are a lot alike, you know. Treat 'em right and they'll reward you with loyalty.