Tales of Yesteryear

The stories, ledgends and tales that are told through the years weave into the rich culture that shapes our American West.

Tales of Yesteryear Articles

| A Broadcast Pioneer of Colorado |

A Broadcast Pioneer of Colorado

Article contributed by Jean Miller How times have changed! Today every TV station has a least two weathermen and every newscast has innumerable weather reports, usually given as fast as the tongues will move and repeating the same information ad infinitum. There was a time when this wasn't so. Back in 1950, TV stations were still unknown in Denver. KOA was probably the most influential of the radio stations. (KLZ was established two and a half years before KOA in 1922.) On New Year's Day, 1950, a slender young man arrived in town from Des Moines, Iowa: his name was Ed Bowman. Ed was born and raised on a farm in Iowa City. He loved weather and he loved to fly. Ed was convinced that in order to talk about weather, one should understand the sky, and flying was the way to do this. Ed had cut his broadcasting teeth with WHO in Des Moines (at the same time that Ronald Reagan was the station's sports announcer). In December 1950, Bowman managed to secure a reporting job in the newsroom for KOA Radio. On Columbus Day, 1952, KBTV (Channel 9) started to broadcast. The following June, KOA Radio was sold by NBC to Metropolitan Television Company, one of the principal stockholders being Bob Hope. That Christmas Eve, KOA radio became KOA-TV, or Channel 4, and for the next thirty years, those were the call letters of this station. Ed Bowman was picked from the radio newsroom to be the weatherman, supposedly because his name rhymed with weatherman. (A bit of a stretch.) For the following twelve years, he was the only full time weatherman in the Rocky Mountain Region. Ed quickly became "Weatherman Bowman" and his distinctive mid-western drawl was well-known to Denver listeners, who turned to his report every day at 5:05 p.m. Ed was also heard in the mornings, flanked by ads for Cream of Wheat. (It's Cream of Wheat weather: let me repeat. Guard you family with hot Cream of Wheat.) Weather reports had no quick-moving computer graphics in those days; no mountain-cams, Denver-cams, highway-cams, or ski-area-cams. Fortunately, Ed was a skilled artist, who, every night, created weather maps right in front of our very eyes. His maps were filled with wonderful clouds and arrows showing wind directions; his "troughs-aloft" guided the listener if figuring out the next day's activity. This was the first time the term "trough aloft" was used to define weather. These hand-drawn maps have become collectors' items. Ed and his wife Madelyn lived with their family in Littleton. He flew his Fairchild trainer airplane every chance he got. One of his treasured possessions was a Norden bomb sight, a highly secret device used during the war, which he was able to purchase from the Air Force afterwards. During this time, before the Air Force Academy was completed, cadets were housed and trained at Lowry Field in Denver. One day, Ed lent two of the cadets his plane, to take for a flight "around the patch" south of the city. Something went wrong during the flight; the Fairchild crashed, and both men were killed. Ed never really got over the loss of these young men. Ed was a congenial fellow, and his no-nonsense approach to weather reporting made him the person to whom everyone turned each day. Emphasizing his background as a pilot and looking more dapper than ever, he sometimes donned goggles and a white scarf, as he gave his report. Bowman occasionally broadcast from his home studio, particularly during severe storms, when driving to the studio in downtown Denver was treacherous. He related how once, when he overslept, there was no time to research the weather. So he hurried to the door, looked outside and found it was raining. He told his listeners that there was a 100% chance of rain and he held his microphone to the door so that they could hear it pouring down! "Just listen to that!" he said. We became acquainted with Weatherman Bowman in the late fifties, because he loved to come to the mountains to stay at Ski Idlewild. Old Dick Mulligan was a colorful fixture at Winter Park Ski Area in the early days, and his wife was a Weatherman Bowman fan. She wanted to meet him in the worst way; so once Dwight took Ed over to the Mulligan's house for a chat. This really made her day! Dwight also lunched wi h Ed frequently when he was in Denver. For six months or so, we sponsored the weather report, which, though expensive, was great fun. Weatherman Bowman left Channel 4 TV in 1965, perhaps not entirely willingly. His fans felt that nobody else ever matched his skill. Ed continued reporting for some time, however, broadcasting for a Kansas radio network from his home studio. Ed Bowman died on July 4, 1994, and he was inducted into the Broadcast Pioneer Hall of Fame in 2001. The Hall of Fame, established by the Broadcast Professionals of Colorado in 1997, is dedicated to preserving Colorado's rich broadcasting heritage, and honoring those who had made significant contributions to this field.

Additional memories of Ed Bowman from reader Glenn Wolfe "Ed Bowman was a favorite of mine. I can't resist a few stories based on the year I worked in the newsroom with him. After the 10-o'clock TV news every night people would come to the lobby of our building because he would give away the hand drawn pastel weather map he had created for the broadcast -- signed, of course. The engineers and camera operators loved the guy. On one occasion we had a surprise, late spring snow storm. During his live TV weather cast the studio crew lobbed snowballs at him. He was so serious about providing accurate, usable weather and forecasting information that he spent some vacation days in eastern Colorado and Nebraska (part of our radio coverage area) talking to farmers and observing the wheat harvest. He wanted to know that they needed to know about the weather. The news room at KOA was a cement block structure with no windows. Ed's desk was right in the middle, connected to various weather instruments on the roof, including a rain gauge. The gauge consisted of a collection funnel on the roof. The water ran down a tube, through the ceiling, to a calibrated beaker right on his desk. Well, it had been an absolutely clear, dry day....not a cloud in the sky. Just as Ed was preparing his broadcast, one of the cheeky engineers peed into that funnel! What a nice man he was, even to this total green horn just out of college."

|

| A Good Man |

A Good Man

A Good Man contributed by Richard Shipman All of us have those wonderful people in our lives who quietly go about their daily activities without complaint. They don't stir up the wind or people's lives with grandiose actions. And at the same time, many of them have a great impact on us. Thankfully, I know one of those people. He is a son of I first met Fred Wood in 1967 when my brother married the eldest daughter of Fred and Mary Wood. It has been fascinating and rewarding to get to know Fred, his immediate family and extended family. The first thing I learned about Fred was his kindness and love of family. Almost immediately I was included in all family activities: the birthdays, anniversaries, and trips back to the family cabin near Williams Fork Reservoir. I was about the same age as his oldest sons and I suppose it was just easy for him to look at me as one of his boys. I was always extended a warm and sincere invitation to come to the annual summer and winter mountain events. We all had great fun, all fifteen to thirty of us. These events frequently pulled in the families of Fred's older brothers who worked the family ranches in the Williams Fork area. Loyalty and dependability are important to Fred. At the end of this year he will complete his 60th year working for the same employer. That is quite an accomplishment these days. He is always there training the new people and sharing his knowledge and work ethic. It says a lot about one's character to stick with something for that many years. Probably the most important accomplishments are the 59 years he has been married to his lovely wife, Mary, and raising their 10 children. Fred works for a moving company. This job requires a great deal of physical strength, much of which he gained working on the family ranch near Parshall, where he was born. I've witnessed his ability to do hard work when we cut trees for firewood, added to the cabin, or dug out the basement. Fred was born in 1924, the youngest of 13 children. Growing up in the 30's gave him a good understanding of the value of hard work and the determination to find a job to support a family. Like most of the people of his generation, the love of family and country put him on a path to service in World War II. It's only been in the last few years that I have learned about Fred's service and how much our country asked of those young people. Fred and his peers have shared some stories and now national authors have recognized the "greatest generation." You see, most of these people are modest and humble folks who were just asked to do a job and they went out and did it with no expectation of special recognition. Fred was a crewmember on a B-24 Liberator bomber flying out of I recently had the opportunity to fly in a renovated Liberator and I am amazed at what little the pilots had for protection. And that they were asked to do so much with so little. Another thing that you learn from these people is humility. The world that they saved us from was so brutal that they have kept it all to themselves for more than forty years. Now as time draws to a close on their times, the remaining crewmembers relish their annual get-togethers. They are always invited to share the cabin. For most of Fred's adult years he worked in You can see where I am going. Here is a man who lived and worked through the country's most trying and challenging times. I can see his strength of character, dependability and devotion to family and friends. Make no mistake; he did not make this journey alone. Mary has been a partner from the first. They have shared the triumphs and tragedies together. And they continue to lead their family. It has been an honor for me to be part of this remarkable family lead by an unassuming, gentle man. I feel privileged to know this good man and to have him as a friend.

|

| A Man Called Blue |

A Man Called Blue

“Blue” should have been a grouch, with a name like that. Nobody who knew him seems to know why he was called this; his real name was Rudolph O. Cogdell. If one went into his little grocery store in Fraser, although his voice was gruff, he gave a peasant greeting. He did possess a temper that could be ignited, and if his blood pressure rose, his face turned a brilliant red. |

| Brrrr! |

Brrrr!

Article contributed by Jean Miller So many people ask if it is true that winters used to be much colder up here. The answer is yes. We could generally figure on one to two weeks of nights between minus 30 degrees to minus 50. This usually occurred between the middle of November and the third week of January. (Please note that we also didn¹t have pine beetle infestations during those years.) We Fraser Valley folk depended on weather reports kept by Ronald and Edna Tucker, who for many years faithfully read thermometers day and night. It was through their efforts that Fraser came to be known as the “Icebox of the Nation”. These were the years when it was guaranteed that the power would go out, usually on the coldest nights when you had a crowd in the house, for the REA had not existed very long and they suffered from many glitches and equipment failures. Occasionally somebody would set his house afire, trying to thaw pipes entering from the outside. The incident I am going to relate was in mid-November 1951, and I had just delivered Dwight to the airport, to leave for his required two weeks Naval Reserve active duty in San Diego. I took advantage of the break to stay with my family in Denver for the night. I was an innocent city girl, and at that time I didn’t realize the connection between being overcast for a week (which we had been) and what happens when the sky clears (which it did). I got home to Hideaway Park in the late afternoon, just after dark. It was so cold! I checked the house and put more coal in the stoker. All was in order. Next I went over to the Inn (Millers Idlewild). As I opened the front door, I heard water running, as in a waterfall. The noise came from the kitchen. When I went to check, I saw a spray of water shooting from the sink all the way across the room, drenching the stove. The floor was an ice skating rink. I couldn’t believe my eyes. As far as I could tell, it was as cold inside as out. I tried to shut off the water at the sink, but the pipe was split. I ran to the laundry room and searched for valves, but everything I tried did nothing at all. At last I drove back to the highway to Ray Hildebrand’s house. He and his wife Mabel had a small grocery store and Hideaway Park’s first post office. Ray, one of the few people I knew in town, kindly came to my rescue. He found the main valve hiding behind other pipes, and the geyser in the kitchen fell silent. Then I built a fire in the furnace. Now I was a poor ignorant city girl. For years my family had had natural gas; when it got cold, we turned up the thermostat. What did I know about stokers, sheared pins, and augers, tuyeres and clinkers? A lot of nothing. That was a rough two weeks. The night temperature was never warmer than 35 below. I mopped up the mess in the kitchen, once the place warmed up a bit and the water thawed, but I just left the split pipe situation for Dwight to deal with. I struggled the whole time to keep the Inn above freezing. I was afraid that if I gave up, every pipe in the place would burst and I was embarrassed to call on Ray Hildebrand again. Dwight’s weeks were finally over and I picked him up once more. I was so glad to see him! Indeed, I hoped he wouldn’t leave again for a very long time. He was a dear boy and I did miss him. Besides, he knew all about pipes and pumps and furnaces.

|

| Christmas at the Crawfords |

Christmas at the Crawfords

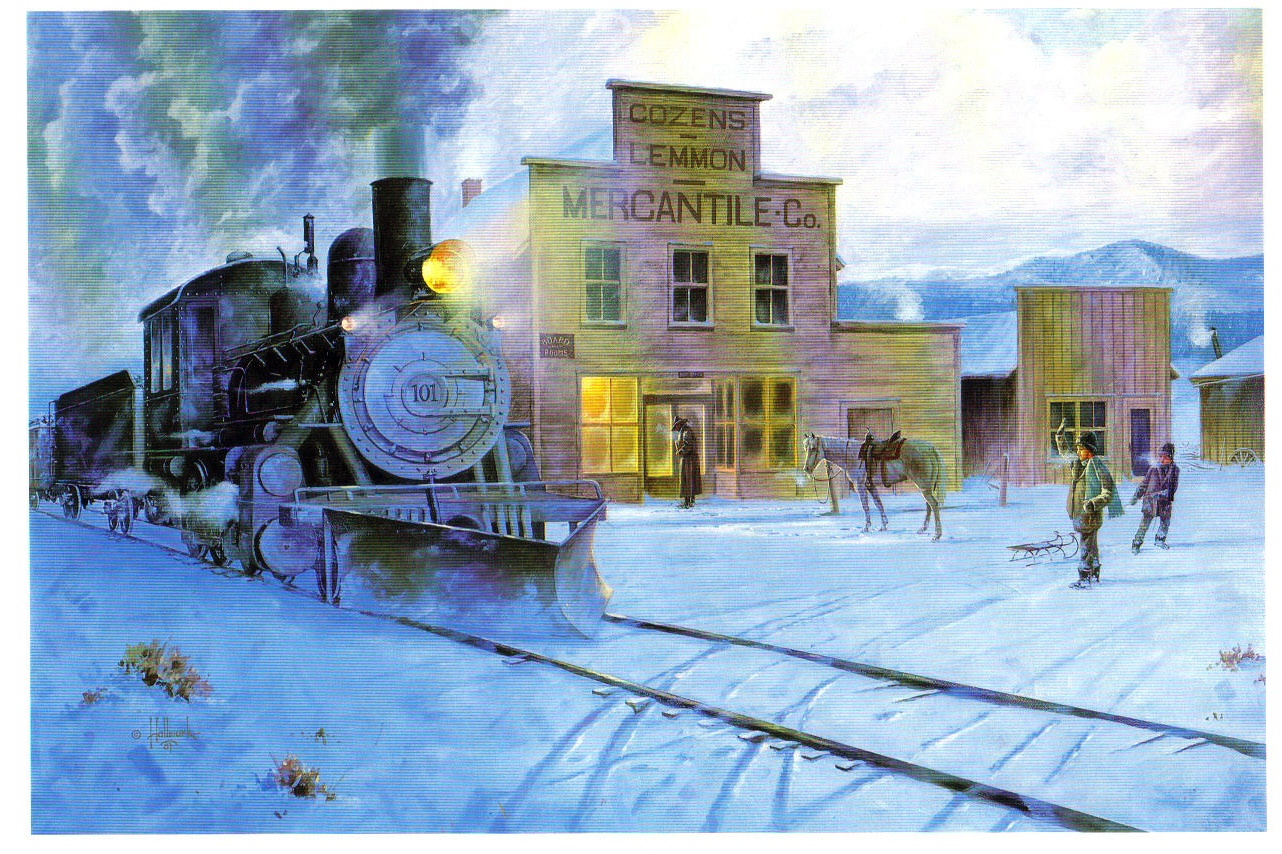

Jimmy and Maggie Crawford settled in Hot Sulphur Springs in June of 1874. They left their farm in Missouri with their three children, John not yet two, Logan 4 and Lulie 7 years old to begin a new life in Colorado. The one room cabin was built of round logs and had a sod roof. In several places outside light could be seen between the logs. The floor was packed earth covered with elk skins which had a tendency to smell while drying out after a rain or melting snow. The sod roof was far from water proof. When the children came down with scarlet fever Jimmy promised to cover the roof with wood shingles and had gone to Billy Cozens' sawmill to make them. Mr. Cozens was very helpful and even gave Jimmy a rusty iron stove to take back home. Rusty or not, to Maggie it was like new. She was most appreciative. The shingles were carefully stacked by the cabin but never made it to the roof. Jimmy carefully explored the area for suitable pasture land for his small cattle herd. His explorations took him further and further to the west of Hot Sulphur Springs and as fall approached he became desperate to locate suitable grazing pasture before the snows. Although Jimmy would return home every few weeks, the time in between his visits became longer and longer as he moved his cows to the west. Maggie was faced with many hardships in his absence. Ute Indians would quietly appear, seemingly from nowhere, and ask for food or as in one instance, ask to trade a pony for the little boy John which she of course adamantly refused. Maggie was able to keep friendly relations with the Utes but never comfortable when they appeared. The conversations were limited to jesters, hand language and a variety of facial expressions. But this is a Christmas Story. To begin with, mountain men, prospectors and just plain loafers from Georgetown would stop by the Crawford's for a meal when they were in the area. Maggie would never refuse them. A few weeks before Christmas four prospectors enjoyed a well prepared venison stew with Maggie and the three children. Lulie, the seven year old told the visitors how she was going to hang a stocking at the foot of the bed for Santa Claus to fill with toys and candy. Her two brothers shook their heads in agreement. Maggie said, "Lulie, I really don't think Santa Claus could find us way out here in Colorado!" She knew there was nothing she had to fill the stockings except maybe some sugar candy which would likely be a disappointment for each of them. Their Christmases in Missouri were memorable with presents, candies and fruit. One of the four prospectors listened intently to Lulie as she described the Crawford's last Christmas in Missouri. He had introduced himself as Charley Royer. Charley was a 22 year old, recently from Kentucky now working in the silver mines near Georgetown. After a very satisfying lunch the men left and a heavy snow began to fall. By Christmas Eve the snow was deep and drifts were high. The temperature dropped below zero. Although Jimmy had promised to be back for Christmas, Maggie thought the snow too deep for him to travel. He had located what he called the perfect pasture far to the west and had made a land claim close to a bubbling sulphur spring. He told Maggie it reminded him of the sounds steamboats made on the Missouri River and named his land claim, "Steamboat Springs." Alone with the children, Maggie read the bible story of Christmas. Before dropping off to sleep, Lulie said, "I know Santa Claus will find us, I just know he will!" Maggie sadly shook her head. Hours later, close to midnight, there was a gentle knock on the door. Maggie cautiously opened the door hoping it would not invite trouble. To her surprise it was the young Charley Royer. He held out a gunny sack and said, "Mam, I've brought some oranges, hope they haven't froze, some candy and a few toys for the children. Please tell them Santa Claus did know where they lived. I remember how important Christmas was for me and I wish you and your family a Happy Christmas." He turned and walked back into the darkness. Charley Royer had come 60 miles from Georgetown in the bitter cold and heavy snow to make three little children happy on Christmas morning with oranges no less, in the middle of winter, toys and candy, a Christmas they would never forget. Jimmy made it home on Christmas day to add to the joy. The following year and many years after the Crawfords had Christmas in a comfortable ranch house in a place called "Steamboat Springs." As for what the future held for Charley Royer, well that's a story for another time. |

| Ed Vucich |

Ed Vucich

Article contributed by Jean Miller Ed stood, ramrod straight, in front of his tiny green house, checking out the day: sky clear blue; clouds soft and fluffy; wind just a light breeze that gently lifted his thin white hair; Brown’s cow feeding in Millers’ yard, as usual; Old Lady “Ada” (aka, Mrs. Zeida) getting ready to water her Oriental poppies. The day was on its way. “Ha! Here comes Dwight to chase off that darned cow. He goes through this every day. I bet one of these days he’ll have fresh cow meat for supper!” Ed returned inside his cabin, to feed the stove and make coffee. The fact was he didn’t need any more heat. He kept the place about 85 degrees, summer and winter. But Ed was so thin, cold went through his worn body easily. Soon he poured himself some coffee and went out to talk to Mrs. “Ada”. “Hello there, old woman. Those poppies are the prettiest you you’ve had for years. You should win a prize.” “Thanks, Ed. I agree that they’re especially nice this summer. Brown’s cow has left them alone for a change.” With a laugh, she went back in her house. Dwight Miller wandered over to chat. “Mornin’, Ed. How’re things?” “Well, just fine, except you’ve got to tell your cabin guests to quite using my outhouse! I saw three of them coming out of there early this morning. Tell them to use their own! I’m going to build me a fence.” Dwight looked apologetic. “Boy, Ed, I’m so sorry. You know, sometimes they just can’t wait, so they invade ours. But I tell you what, I’m going to put in a regular bathroom at the back of my garage, facing the cabins. I hope, at least, that will take care of the problem. In fact, if you want, I’ll give you a hand on your fence. I don’t blame you for being irritated!” Ed was mollified with this offer. He had lived in his cabin for some years now, after finishing up his days as a tunnel worker in 1927. He used to tell Dwight, “Back then, there were prostitutes behind every tree up near the tunnel, and if you paid them a quarter, they’d give you 15 cents change!” He was Austrian and had served many years in the Austrian army, but he got fed up with all that and came to Colorado to live. The mountains reminded him of his home country, and his life style remained just as spare and regimented as it had been in the army. Everything was neat as a pin. The old man kept track of his neighbors’ comings and goings, including Dwight’s wife, Jean, and their toddler, Martha. He used to really fuss at Jean, because she insisted on whistling. “Jean, ladies don’t whistle!” But Jean liked to whistle, so she continued not being a lady. The baby was another subject. Dwight had built a ladder coming down from their apartment on the upper floor, as a second exit in case of fire. Martha learned to climb down that ladder before she was three years old. “Dwight,” Ed would protest, “that baby is going to kill herself! She¹s going to fall; then where will you be?” But Martha seemed to do just fine with her climbing and she never did kill herself! One day Dwight bought a small Army surplus life raft. Opening it, he discovered some dye, to be dumped into the ocean so that planes could spot men in the water. “Hm-m,” he thought, “I wonder if this dye really works?” So he went up to the bridge over Vasquez Creek and poured some dye into the water. Yes, indeed, it worked. The bright red color spread into a great circle in the creek and promptly flowed downstream. Dwight hightailed it down to his house, to see if the color still held. Here it came, and here came Ed Vucich, madder than a hornet. He had spotted the dye and was quite positive that Dwight was trying to poison him and all the others who used the creek water for drinking. In spite for fretting and stewing over illegal outhouse use, “poisoned” water, babies on ladders, and unladylike whistling, Ed cared for the young couple. On day as Dwight and Jean were about to head into Denver, he came rushing out and stopped them. “Here, I have something for you!” And he presented two beautifully baked potatoes, straight out of his oven. They were perfectly lovely. Ed swore up and down that he didn’t drink, but in fact, he was known to visit Wally’s Bar on the highway into town. One bitterly cold night, Dwight and Jean heard a rumpus going on outside. In those days, winter temperatures dropped regularly to minus 40 to minus 50 degrees. Getting out of bed, the pair went to look out their front window. Ed was attempting to get into his house, which he kept locked with three different padlocks (why was a mystery; he had very few belongings). Perhaps he wasn’t drinking, but he certainly wasn’t sober. He tried to open a lock; his feet slid out from under him and he swore, “Damn!” He struggled back onto his feet again. Same result. The young people didn’t dare just leave him, hoping he would finally get into his house he’d have frozen to death. But if they had interfered, oh, he would have been furious. So they watched until at last all three padlocks were open and the old man staggered inside. They never told him about the show he put on! Ed lived in Hideaway Park for a number of years longer, but it’s uncertain as to where he is buried. Dwight is convinced there probably aren’t as many characters in the valley as there were fifty some years ago.

|

| Ninety Four Winters So Far |

Ninety Four Winters So Far

January, 1911. Five years ago they were teenagers in Torsby, Sweden, oblivious to the sweeping changes that history and hope would bring to their lives. Now they’re in a mountain valley halfway around the world from their Scandinavian homeland, marveling at the tiny bundle of flesh and spirit who has just joined their family. It’s the coldest week of the year in one of the coldest spots in America, but there’s a fire crackling in the woodstove, and their hearts are warm with love for each other and their firstborn child. For the next few days, a parade of fellow Swedes stop by to pay their respects to the newest resident of the town of Fraser: Elsie Josephine Goranson. |

| The Great Kaboom |

The Great Kaboom

Article contributed by Jean Miller Bill Cullen moved to Hideaway Park from Berthoud Falls in 1961, at which time he bought several pieces of property. One was the filling station and the Village Inn, priced at $25,500, belonging to Wally and Dottie Tunstead, who had come to town right after the war. The Tunsteads moved back to Oklahoma, their former home. Behind Tunsteads’ stood a very small, old house, on land possessed by Easy Butler; Bill bought this too, in 1963, as well as a house near Vasquez Creek, owned by an old-timer, Charlie Tigges. Next he bought old Mrs. Zeida’s house; she had died in 1964, and when her son Joe came to clear it out, Bill hightailed it over to see him. “I’d like to buy your place. Would you be interested?” Joe was definitely interested, so the two came to an agreement on the price: $100 down and $50/month. Adjacent to this was land belonging to Marie Roth, which Bill had already bought, and the Roth/Zeida properties formed the nucleus of Bill’s “homestead.” One of his first projects was to put in an access drive to the house, for there was none. Few of these people drove, you see. Almost immediately Bill discovered that there was a huge rock in the way, one which wasn’t going to be moved with just a pick and shovel. Wandering over to see his friend, Dwight Miller, he inquired, “Did you by chance have any dynamite left over after blasting those beaver dams the other day?” “Why, as a matter of fact, I did,” answered Dwight. “What do you need?” Thus it was arranged for Dwight to come blast that rock out of there. Now Bill’s driveway was to be built along the very edge of his property, which also happened to be very close to the home of Mrs. Hart, who lived with her son, Ken, and his children, Beverly and Danny. Bill and the Harts always had a running battle going. He had gotten cross-wise with Ken, when he blacktopped the road in front of the Village Inn filling station, thinking to make it easier for customers. Because Bill and Dwight were friends, by extension, Dwight was also Mrs. Hart’s enemy. Mrs. Hart was a crusty old gal and when she saw that something was a-foot, she hustled out to protest. “You two’ll have holes knocked in the roof of my house with all that blasting! You can’t do it.” Bill thought a moment. “I see your point, Mrs. Hart. I tell you what. I know where there’s an old mattress. We can put that over the rock and it will contain the sound as well as odd rocks that might go flying.” So Bill and Dwight headed down to the little house behind the Village Inn. It seemed that some fellow was renting it from Bill and he hadn’t bothered to pay his rent, minimal as it was, for at least four months! Without a qualm, the friends brought back a rather ratty mattress that would do the trick perfectly. Dwight dug down next to the rock and carefully stuck his sticks of dynamite around it. They laid the mattress over the top and placed the fuse leading away from the rock. Mrs. Hart stood, glaring at them from inside her house. The moment had come. Dwight lit the fuse and the two men ran off to a safe distance. A few moments later --- KABOOM! Dwight and Bill saw the mattress rise and rise, higher and higher, up to the very tops of the nearby pines. They heard the rattle and clatter of small rocks tumbling and skittering off Mrs. Hart’s roof. They watched that furious old woman rush from her house with fire in her eyes, almost before the mattress had a chance to make a safe landing. She was ready to tear them limb from limb! But they checked her roof, and amazingly there was no damage at all. What a bit of good fortune. They inspected the rock and found that it had shattered beautifully! Bill would have no problem at all in building his road now. Dwight did earn from this project, however, that there were some things he didn¹t know about blasting rocks! As for the mattress, they searched for it. I can assure you that that mattress was never going to look the same again. Off to the dump it went, at least those parts of it that could be found!

|

| The Mighty Forty |

The Mighty Forty

Article contributed by Jean Miller The Middle Park High School band wasn’t much to brag about, and that’s a fact. Several members were very capable young musicians, however. For instance, Stuart played a hot set of drums that set people’s feet to tapping and hands to clapping. Debbie was an excellent trombonist, good enough so that one year, she was invited to march with Pierre Laval’s All American High School Band in the Rose Parade! And Jack was right behind her in skill. Martha led the flutes beautifully, and there were Alan, Bert, Roxanne, Carolyn, and others. But the group never seemed to coalesce into a single playing unit.

Then a Music Man came to the school. Wes Robbins was a showman; he was enthusiastic; he had flare; he had color. He took those young people in hand and soon had them marching in time down the same street. People flocked to hear the music, whereas before, they just groaned. By the end of the school year, Mr. Robbins decided that the band needed uniforms, sharp uniforms to match the cool music. Now most of the extra-curricular funds went into sports, particularly football. But the band leader convinced the administration that with uniforms, the band would rouse the fans to a high pitch, encourage parents and family to attend games, incite the teams to greater, and winning, efforts. So he got the uniforms. That fall the band players tingled with excitement as they waited to try on their new duds. They looked wonderful. All the effort was worthwhile. But Mr. Robbins didn¹t stop there. Every spring, on the first weekend of May, Canon City held a Blossom Festival. Bands from all over the region came to march and compete. The Middle Park Band proposed to join this event! You must understand, there were only forty students in the band, for this was a small district still. When the youngsters arrived in Canon City, they met bands from Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska, as well as from New Mexico and numerous Colorado schools. Many of these bands had 100 to 120 or so members! All were much larger than our little group. The Middle Park students felt rather overwhelmed. But it wasn’t long before the big bands had adopted this nifty minuscule band as a mascot. Saturday came and the bands lined up at the foot of the Canon City prison wall. Just then, two inmates jumped from the top of the wall, presumably planning to escape into the mob of students and onlookers. Prison guards shot the men dead in the air. This rather rocky start for the event didn’t phase the boys and girls; the parade commenced. Grand County enthusiasts lined the edge of the avenue as the bands marched down, drums beating, horns tooting, and music filling the air. “But where is our own band?” they wondered. Suddenly, applause erupted and you could see why. A Nebraska band of some 120 members filled the street. Shortly after, striding bravely along, a compact band of forty students in spiffy navy blue uniforms, played beautifully and vigorously. Following behind them was another band of over 100 members. The contrast was astounding and people loved it! Clapping onlookers whistled and shouted. That afternoon the many groups competed on the football field, doing intricate formations as they played their music. Middle Park picked up two first place ratings for their performance that day. That was truly a triumph for our musicians, as they realized that even though they were small, they were mighty. This must have been about 1971. |

| Welcome to Middle Park and Grand County! |

Welcome to Middle Park and Grand County!

Story Contributed by Jean Miller Sam Conger worked long and hard in 1861, panning for gold along Coon Track Creek east of Colorado¹s Continental Divide; his findings encouraged him to follow the creek on up to 9800’. Arapahoe Indians of that area told him about their “Treasure Mountain” and when the government moved the Indians out, Sam resolved to explore. By the summer of 1869, he and five partners had found silver, enough to stake out the Caribou and Conger mines. A year later, the little town of Caribou was established to house miners that flocked in. Hopes were high and Caribou City soon had a church, three saloons, a brewery, and a newspaper to provide for the 400 people who lived there. Eventually, this district produced an estimated $8 million before closing in 1884, enough to give rise to Colorado’s being dubbed the “Silver State.” The area also became known as “The Place where Winds were Born,” for it was always windy, with plenty of snow to go with it. In September 1879, nearly the entire town went up in flames. Among those who lost their homes and belongings were Ben and Laura Simpson. The couple and their children found a place in the budding town of Nederland, where they stayed for six months while they decided what to do. Although the town was soon rebuilt for a population of 549, the Simpsons weren’t sure they even wanted to remain. Ben told his wife, “I’m thinking I’m not really cut out to be a miner. I reckon I’d like farming or ranching better.” Word was that Middle Park, west of the Divide, had fine open meadows, ranch land, and plenty of water. “That sounds hopeful,” commented Laura. But how to get there was another question. To the north no roads existed, all the way to Wyoming. Indians sometimes entered the Park by way of the Milner Pass area or over Flattop Mountain, but that was a long way from Caribou. To the south, the Crawford family, in 1874, had used a road of sorts, built by J.Q.A. Rollins; but that too was a long way from Caribou. Berthoud Pass also had been opened in 1874, but that was even farther to travel, and walking was the only choice the Simpsons had. As it was, several trips would be necessary to get their meager possessions all moved. However, Ben had heard of a closer Indian trail that led over Buckhannon Pass (sic). Simpson knew that there was fairly flat country between Caribou and a branch of St. Vrain Creek, which drained from Buchanan Pass and was closer at hand. “We’ll go that way,” said Ben. “I figure we can make it one way in a week or so, at least, if we don’t get lost.” Now, what we call “Buchanan” Pass and Creek today is supposedly named for James Buchanan, the pre-Civil War president, who was also president when Colorado Territory was created. Be that as it may, early maps of Colorado, including Hayden’s 1877 Atlas, don’t name the pass at all and it’s uncertain if, in fact, this is so. July was well along when the family packed the first load of their belongings, along with food that wouldn’t spoil. They headed out, the children driving or leading their stock. Chickens were confined in coops, lashed to horses’ backs and the pigs in crates, to mules. Progress was not difficult to start with, though it was slow, for Ben often had to scout on ahead. He had only a very sketchy map and there were no roads to follow. Still, the family was glad to stop a bit and rest and to let the animals graze. It took most of three days to reach the St. Vrain and locate the rumored Indian trail. Tall aspens and pines crowded the forest here and the ground vegetation was thick, with large boulders scattered everywhere. “Keep those critters moving,” Simpson told the children. “Don’t let them wander. I want to get to the top of the pass today, if we can.” Pines gradually gave way to moss-festooned spruce, but finally, the faint trail left the forest and opened onto bare, glacially-carved terrain with spectacular views of what today we call Indian Peaks, rugged, with sheer cliffs, surrounded by huge boulders. Even though t was mid-summer, they met drifts of deep snow as they climbed higher and they had to pick their path through the wet and slop. The horses and mules plunged and pawed their way through, chickens squawking frantically and pigs grunting uneasily. The final stretch of the narrow path was steep enough that they had to make several switchbacks up the rock face to the tundra on top, almost 12,000’ high. A chill wind quickly dried their sweaty faces, and everyone was happy to stop for a breather. The view was stunning; Sawtooth Mountain towered to the southeast, with its flat summit and sharp drop-offs on three sides. Alpine grasses and flowers of the most brilliant colors grew between flat lichen-covered boulders atop the crest. The animals fell to grazing eagerly while the Simpsons looked west towards what would be their new home. Soon, though, Laura said, “Let’s move on down, Ben. I¹m getting chilled, and I see a thunderstorm building over that way. I don’t want that to catch us on top here. They scare me.” So the little group moved down the easy tundra slope leading northwest, until they spotted the descending trail. This soon dropped steeply to a bench. Here and there the spruce forest opened to meadows, soggy with melting snow and filled with little creeks, tarns, and abundant flowers. Parallel to their route, Buchanan Creek gained momentum as it plunged downward, and whenever the canyon narrowed, the immense amount of water crashed and tumbled over the large boulders, creating a tremendous and frightening roar. “Don’t anybody get near that creek,” cried Ben. “If you fall in, we’d never get you out!” When the Simpsons saw that the trail, such as it was, seemed to split, they chose to go right, which seemed more moderate. “That creek spooks me, with all its noise,” said Laura. The forest was lodgepoles and aspens now and everyone was pleased when they came to a large, deep lake with boulders surrounding the water’s edge; they heard later this was Gourd Lake. “Shall we camp here,” suggested Ben? “No,” said the children. “It’s too wet!” On they trudged then, down another very steep drop, switchbacking through the trees as well as they were able. At last, scrambling over unstable, loose rock, they reached the valley where another large stream cascaded down on the left, to join Buchanan Creek. The way eased and the valley gradually opened until finally, to everyone¹s delight, a huge park appeared, with meadows filled with grass turning golden in the summer sun, sparkling streams, and kindly hills surrounding all. The end of their trek was at hand. Just then Laura spotted a rider on the far side of the meadow. The man turned out to be Henry Lehman, a recent homesteader and rancher, one of only three in the area. “Welcome to Middle Park and to Grand County,” he cried. When he heard who they were and where they had come from, he said, “Stay the night with us. My wife will be delighted to have company; she sees so few people.” The Simpsons were overjoyed at such a welcome. Then Henry added, “You can rest with us a few days and leave your things here until you have fetched your other belongings. We can talk about where you might settle and even help you build a cabin before winter.” Thus it was that Ben and Laura Simpson found a new home in this green oasis of Middle Park. Sources: Louisa Ward Arps: High Country Names,GCHA Journals:1982 The Journey 1987 Indians of Middle Park, 1985 Ranching and Ranchers Henry Lehman, Deborah Carr, Hiking Grand CountyTrails and other hiking experts, Robert C. Black III, Island in the Rockies &l ;/P> <

|

- 1 of 2

- next ›