The Wolverine Mine was discovered in 1875 by James Bourn and Alexander Campbell. Bourn was the brother-in-law of James Crawford, the founder of Steamboat Springs. James Bourn was the twin brother of Crawford's wife, Maggie. A Grand County recording error forever changed the name of Bourn in the area to "Bowen". The mine was located in the Rabbit Ears Range on Bowen Mountain, up Bowen Gulch, approximately 10 miles northwest of Grand Lake. This discovery sparked additional exploration in the area that lead to a number of new mines. Within a week of the original discovery, interested parties formed the Campbell Mining District which included Bowen Mountain, Bowen and Baker gulches. Some of the Middle Park residents who participated in the mining exploration were John Baker, Charles Royer, Charles Hook, John Stokes and the Redman brothers, William and Mann. The Redman's eventually discovered the Sedalia mine. Bourn and Campbell in less than a year lost the Wolverine mine by not fulfilling a grubstake agreement with the Georgetown grocers, Spruance and Hutchinson.

John Stokes leased the Wolverine Mine from the grocers until Edward Phillip Weber, an agent representing a group of Illinois investors, purchased the Wolverine Mine in the Summer of 1879. Weber continued purchasing other Campbell Mining District claims which created a great deal of local excitement. Weber hired Stokes to assist him and also hired Lewis Dewitt Clinton Gaskill to act as the first foreman for the Wolverine mine. Gaskill had mine operation experience, having successfully operated the Saco Mine, on Leavenworth Mountain, above Georgetown for several years. A mining camp was built below the Wolverine Mine that contained a large bunk house building and a more substantial mine office building.

Gaskill, a Civil War veteran of the 28th Regiment of the New York Volunteer Infantry, had come to Colorado in 1868 as a representative of a group of Auburn, New York bankers to invest in mining properties. He eventually successfully operated the Saco mine in 1873 and 1874. He invested in the Georgetown, Empire and Middle Park Wagon Road in 1874, which was a toll road that finally made the Berthoud Pass road passable for wagon traffic. Gaskill also acted as the foreman during the construction of the road. The principal investor in the road was William Cushman of the First National Bank of Georgetown. The bank had a financial collapse in 1877. At that time, Gaskill was the secretary of the road company and lived with his family in the company house just below the summit of Berthoud Pass on the west side. William Hamill, a wealthy Georgetown businessman, bought the wagon road in a foreclosure auction in 1881 for $7,000. Gaskill continued to live with his family in the Berthoud Pass summit house until 1885, when he moved his family into the Fraser Valley and homesteaded 160 acres along Elk Creek.

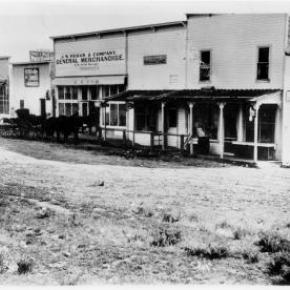

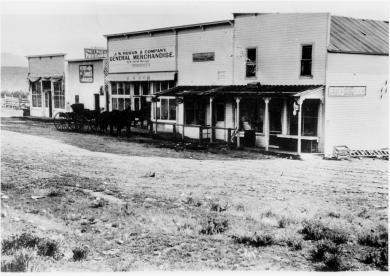

The settlement of Gaskill began when in August of 1880, Al J. Warner built a log cabin store in a meadow below Bowen Gulch on the trail/road that lead to both Bowen Gulch and Baker Gulch. The settlement was also strategically well placed midway on the trail/road between Grand Lake and Lulu City and the Lead Mountain Mining District. Another store was built in September by John K. Mowery. By that October, Mowery was appointed as the first postmaster of Gaskill. The following spring E. Snell, opened a large general merchandise store that prompted the original store keeper, Al Warner, to relocate to Grand Lake as Al's Place. The town was named to honor L.D.C. Gaskill, the greatly respected foreman of the Wolverine Mine, the road builder/operator and the Civil War veteran. By 1882, the town covered 60 acres. E.P. Weber of the Grand Lake Mining and Smelting Company got involved in the town real estate development by laying out a city grid and offering lots for sale. Weber's plat renamed the town Auburn after L. D. C. Gaskill's home town of Auburn, New York, but the Gaskill name stuck. By the close of 1882, there were over 100 residents living in Gaskill. The most substantial building was the Rogerson House, a well appointed two story, squared log hostelry, Horatio Bailey Rogerson, proprietor. Rogerson, would be elected County Commissioner in November of 1882, but would not serve because of a sudden discovery of ineligibility. Instead, lame duck Colorado Governor Pitkin, appointed E. P. Weber to the post. Weber was killed in the infamous July 4, 1883 shoot-out at Grand Lake.

The Bowen Gulch trail lead to many of the most productive and worked mines in the Campbell Mining District which included the Wolverine, now owned by the Grand Lake Mining and Smelting Company, E. P. Weber superintendent and the Ruby and Cross mines owned by Kentucky and Colorado Mining and Smelting Company, John Barbee superintendent. Barbee, who lived in Grand Lake, would go on to serve as superintendent of schools, Justice of the Peace and briefly the editor of the Grand Lake Prospector. Barbee's partner in many endeavors was Antelope Jack Warren. Warren was as rough as Barbee was refined. He acted as a foreman and, by one account, a bodyguard for Barbee. The Bowen Gulch trail continued up the mountain to Bowen Pass and then descended into North Park and the Jack and Park mining districts which were organized by the end of 1880, to the settlement of Teller City. Passable roads that could handle wagon traffic were needed and often planned but rarely built. The high cost of building and maintaining wagon capable roads in Middle Park was a difficult proposition for local governments and private entrepreneurs.

The Grand County Commissioners in July of 1877 had declared the trail from Grand Lake to the mining gulches of the Rabbit Ears Range to be a county road. However there was little county money to pay for improvements to make the trail a road. Private investors were reluctant to invest in wagon roads when there was the persistent rumor that railroads were coming spawned by the numerous railroad surveys that were performed in the area. Albert Selak, a Georgetown brewer, in August of 1878, organized a toll road that would branch off of the Georgetown, Empire, and Middle Park Wagon Road at the Ostrander Ranch on Red Dirt Hill, and proceed to Grand Lake and continue on to the Rabbit Ears Range mines and continue on into North Park and on to the Wyoming territory line. John Barbee invested in the Middle Park Toll Bridge Company, a toll bridge company that intended to build a bridge across the Grand River above the confluence of Willow Creek and the Grand River. However, this project languished, and was taken over by the county with an expenditure of $150.

If ore wagons would need to haul ore to the nearest reduction mill which was over 60 miles in Georgetown, the toll road might have been a financial success. However, the lower grade ore from these Rabbit Ears Range mines would not yield a sufficient profit to cover the transportation and processing costs in a market where the market value of silver annually declined. So the ore piles grew. What was needed was a nearby reduction mill or cheaper transportation, like a railroad or a higher price for silver. Weber had repeatedly promised that a reduction mill was coming, but nothing was ever built. By April of 1883 with tons of ore piled up and waiting for transport to be processed, Weber temporarily closed the Wolverine Mine and laid off his miners. He admitted in June of 1883 that the ore from the Wolverine was “rather refractory” and that it would not justify shipment without local reduction. Some hoped the closing was a strategic move by Weber to trigger a sell off of area mining properties so that he could acquire additional mines before he built the reduction mill, but it was not to be. Weber would soon be shot dead by his political rival, John Gillis Mills.

The favorable newspaper stories of Rabbit Ears Range mining would continue, but for the informed, it had become clear that without a major investment in improved transportation including a railroad or a major investment in a reduction mill in the area, the mining concerns were doomed to fail. Mining claims had to be worked in order to be kept. A minimum of $100 of labor or $500 in improvements had to be expended each year to maintain the claim or else the claim would be deemed abandoned. Many claim holders leased their claims to miners to work for a percentage of the return. Without the ability to sell and process the ore for a profit, there was no return. The speculative mining investment money began to dry up and the miners and their supporting merchants began to leave. By the end of 1886, the Middle Park mining boom had ended. To further add to the decline, a border dispute that arose between Larimer County and Grand County over the taxation and mineral wealth of North Park was finally decided in 1886 by the Colorado Supreme Court in favor of Larimer County. North Park was part of Larimer County, not part of Grand County. A lawsuit would follow so that Larimer County could recover the wrongly collected taxes of $20,000 from Grand County. Grand County's total tax income at the time was less than $3,500 a year.