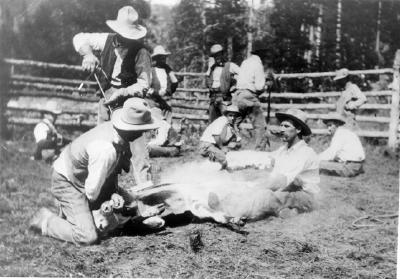

Real Estate and land ownership have always been important to the Granby area. With the passage of the 1862 Homestead Act by Congress, the West, including the area around the current town of Granby, began to be settled with hardy, ranching pioneers. The opportunity to own land was often made possible by homesteading. This lured many settlers to the area.

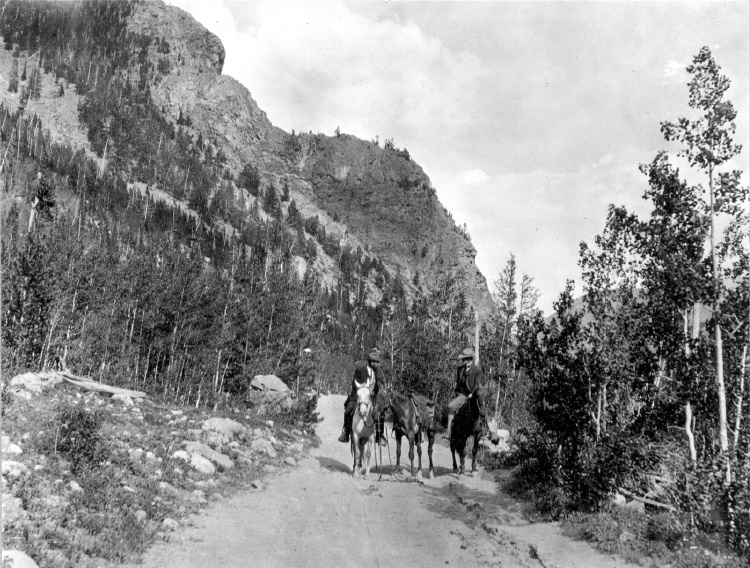

As Congress adjusted the homesteading rules over the years to allow for larger acreages which would support ranching in the Middle Park, towns began to grow. Ranching, mining and especially the railroad fueled the growth. In 1902, railroad visionary, David Moffat, set events into motion in Denver to build a steam railroad from Denver to Salt Lake City which would be built over Rollins Pass. This was a monumental task which led to the founding of the town of Granby.

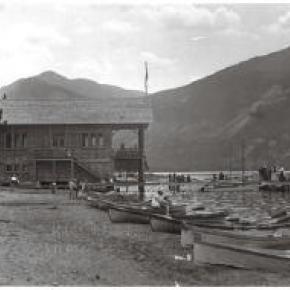

Mary Lyons Cairns observed in her book, “Grand Lake in the Olden Days,” “Granby came into being with the Moffat Railroad, which reached that point in September, 1905. The town site was laid out on a piece of land which was part of a homestead and part of a pre-emption taken up by James Snyder from the government. Mr. Snyder sold this land to David Moffat who had the town site surveyed and platted in 1904, and a man named Hunter auctioned off the lots.”

The lots on the town plat were 12 blocks and a Block “A.” Each block, except Block 12 and “A,” would have 32 lots. Each lot would be 25 feet by 125 feet. Block 12 only had 20 lots. Block “A” only had four smaller lots. David Moffat and the railroad in the form of the Frontier Land and Investment Company designed the town streets so that the southern boundary of the town was Agate Avenue, the western was First Street, and the northern boundary was Garnet Avenue. A variation in terrain in between Block 12 and Block “A” created Opal Avenue that would lead down Fifth Street which would be the eastern boundary of the new town of Granby.

The new town streets were named Agate, Jasper, Topaz, Garnet and Opal, all precious gems which might reflect the mining heritage. But, in the King James version of the Bible in the Book of Revelation, Chapter 21, Verse 19, heaven is described as, “And the foundations of the wall of the city were garnished with all manner of precious stones. The first foundation was jasper…” Other streets and foundations are described as being made of precious gems such as topaz and chalcedony. Agate is described in the dictionary as a variegated variety of quartz or chalcedony. Maybe the founders thought Granby was “heaven on earth.” Or, at least the real estate marketers wanted buyers to think that.

The real estate advertising in the December 16, 1905, Grand County Advocate showed V.S. Wilson as the local real estate agent for Granby. He also was the newspaper editor and became Granby’s first mayor on December 11, 1905. With that background, hyperbole and adjectives must have been in his blood. “Now is the time to buy property at Granby-The newest and best town on the ‘Moffat Road.’…It would be a Happy Christmas investment. Do it now,” was part of the ad copy. Mr. Wilson became one of the first land owners in Granby buying lots 18 and 19, Block 7 on Topaz from Frontier Land & Investment in November, 1905.

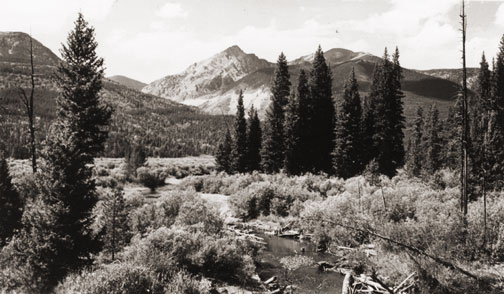

When the railroad’s real estate company founded Granby in 1905, local historian, Betty Jo Woods, said the new town location was chosen because it had great connections with the stage route to Grand Lake, was mostly dry ground, and had pleasant views. As they say in real estate, the three keys to successful land investing are “Location, location, location!” The locations of many of the historic buildings were on the north side of Agate Avenue. According to photographs and written explanations by the late Vera Snider, in 1920, on “main” street, one of the only buildings on the south side of the street was the firehouse which protected the fire pumper and hoses. The post office was also on the south side. Vera Snider later arranged for the preservation of this historic structure built in 1910 by moving the first post office building in the 1960s from 458 East Agate where it had stood for over 50 years to its present location at 170 2nd Street.

According to the current owner of this historic structure, Deb Brynoff, “When Ron, my husband, was remodeling he found old letters in the wall from when it was the post office building.” It was not unusual during the early years of construction for letters and newspapers to be “stuffed” into the walls to help increase what little “R-factor insulation” existed. Other early buildings which still exist in Granby are a home at 127 4th Street which was built in 1909. The current Re/Max Granby office at 247 Agate was a home originally built in 1909. Other early Agate Avenue buildings still thriving are Crafter’s Corner at 295 East Agate built in 1913 for the Granby Mercantile. Local lore says the basement was used as a temporary morgue during the 1918 flu pandemic. However, no historic research has yet been found to document this information.

Research on High Country Motors at 277 East Agate reveal it was originally Middle Park Auto which grew up with the town of Granby. The tax rolls indicate 1913 for the birth of this building. The business was “born” in 1915 when Jack Schliz founded Middle Park Auto. During Granby’s early years this was a hub for locals. It even included a small medical-first aid station inside it before Granby had any local medical services. In 1938, the business was sold to Glenn Pharo and Morris Long. Later, Jack Shield was associated with the business. The authorized Ford dealership was later purchased by Fred Garrett, who later sold it to Mike and Kimberly Garrett. The only constant on Agate Avenue is change. Many of the buildings have a colorful past. For example, the current location of Brown & Company at 315 East Agate was a Texaco Service Station built in the 1930s.

The Long Branch at 185 East Agate is in a building that was Granby’s first strip mall. That accounts for the many doors fronting on to Agate. Built around 1938 for the Craig’s Café, it has housed Olson’s Café, a Laundromat, a barber shop, The Carpet Wagon rug store and Maureen’s Clothing Store to name a few. The Silver Spur Saloon & Steakhouse at 15 East Agate used to be the Grand Bar and Café run by Dick and Beulah Samuelson from 1944 to 1964. The original business at this location was the lettuce shed where the famous Granby Iceberg Lettuce was delivered by local growers for shipping to the Broadmoor Hotel in Colorado Springs. Some of the original lettuce shed has been incorporated into this building.

The Dick Samuelson family also has a history with the Granby Mart at 62 East Agate. This building at one time was the home of Bud and Ken Chalmers’ Auto Repair Shop. In the early 1940s, it had a dirt floor when Sonny Samuelson and his Dad bought it. Clyde Redburn had a bowling alley on one side. The Samuelsons later put in more bowling lanes. Upstairs they had a club called “3.2.” At the time, those 18 and older could sip the 3.2 beer served there and dance. At one time Wayne Snyder’s Saddlery shared half of the store. Sharing a location was the thinking behind the former Minnie Mall located at 480 East Age. Named by local businessman, Jack Applebee, for his mother, Minnie, in the 1980s, many businesses enjoyed the convenient location, The Furniture Store, Hobby Shop, Montgomery Wards, Honey Bear Children’s Clothing, Fabric Nook, Greg Henry’s Get-N-Pack, Radio Shack, Julie Sneddon’s Cards and Gifts, Patti Applebee’s Nimble Needle, Ben’s Aspen Leaf Café and the Shaft Shop which specialized in darts and dart supplies. Today, Granby Medical Center-Centura Health is at this historic downtown location.

Granby’s historic story from 1905 to 2005 is one of building dreams, homes and businesses to create a community. Chinese Proverb says, “One generation plants the trees; another gets the shade.” How true.

2005