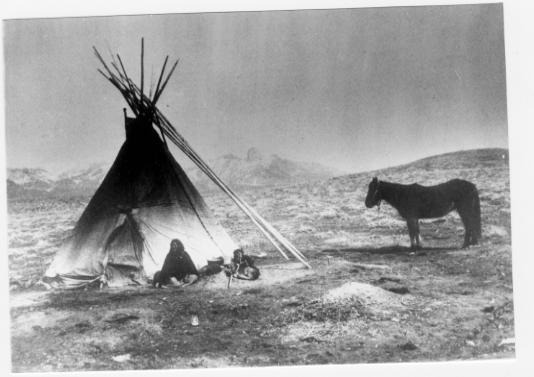

Travel across various passes of the Continental Divide occurred long before white men showed up. Indeed, as anthropologist James Benedict wrote c. 1975, some 10,000 years ago, prehistoric Indians camped, hunted, and built hunting walls on the upper reaches of Rollins Pass, as well as moving in and out of Middle Park for the warm summer months.

Historic Indians followed the same paths. In the earliest days of non-Indian access, a particular pass at the head of Boulder Creek was dubbed Boulder Pass. Capt. Jacob Bonesteel, including wagons, made the first recorded crossing by a white man at this point in April 1862. Three years later, a group of Mormons brought wagons over this route and a year later, promoters of new roads into Middle Park brought in many wagons and livestock.

In fact, tourists were starting to enter the park by a number of routes, and one of them, Samuel Bowles, who wrote a fascinating account of his trip, including his return to Denver via Boulder Pass. Interest was growing rapidly for a road over the Divide, into Hot Sulphur Springs, and on into Utah. One promoter, John Quincy Adams Rollins, from New Hampshire, teamed up with William N. Byers and Porter M. Smart to carry this project through. Rollins was interested in crossing the Divide; Byers was promoting the Springs; Porter wanted to develop the valley of the Middle Yampa. All three were pushing to have Middle Park officially named as Grand County, a challenge finally accomplished in 1874. So Rollins and associates started his road, reaching the top in 1873.

That next winter, they publicized this access and in June, Jimmy Crawford brought his family and wagons to Rollinsville and thence to Yankee Doodle Lake, ready to cross the pass now named Rollins Pass by the developer. But the road ended, and they found Rollins' men still hacking the road out of the granite! Jimmy and his crew found it necessary to leave their wagons and help. Finally, on June 10th, the family was able to head for the top. Jimmy borrowed two yokes of oxen, hitching them to mules, and then to his horse. The road was so rough that the procession could proceed but a few feet before having to rest. The family itself climbed on foot. At the summit, they discovered only a rough swath cut down through the trees on the western side. The "road" dropped down between the lakes and followed Ranch Creek to its junction with the Fraser River.

Rollins quickly realized that Berthoud Pass, which also opened in 1874, was superior to his own pass for wheeled vehicles, so he determined to hedge his bets. He initiated the first mail service into the county in 1873. He also built a commodious hotel where his road joined the Berthoud Pass road at the confluence of Crooked Creek and the Fraser. He called it the Junction House. Next, he proposed to the builders of Berthoud Pass that they form a joint ownership of the two roads between Junction Ranch and the Springs. Tickets would be issued for both routes and revenues would be shared. The two companies would build a bridge over the Grand at Hot Sulphur Springs. He even buttered up his rivals by complementing their work. All this was accomplished, although the mail route soon moved to Berthoud Pass, because of the severe winters on Rollins Pass.

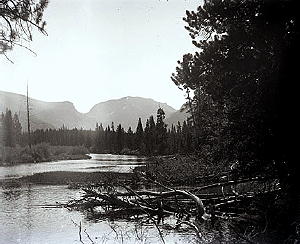

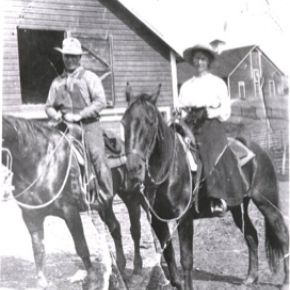

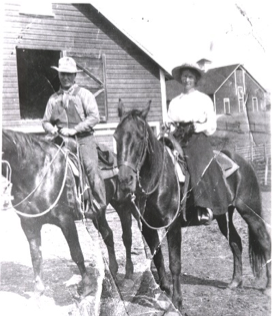

The bridge was started in November 1874. From the beginning, Rollins' road was preferred for trailing livestock, because there were fewer problems with heavy timber and bogs. For years, the Church brothers, George and John, who introduced the Hereford breed into the county, trailed their cattle for summering in what became known as Church Park. However, tourists such as Irving Hale still drove wagons over Rollins Pass in 1878. About 1880, interest burgeoned for bringing a railroad up South Boulder Canyon and through a tunnel near Rollins Pass. Numerous surveys were completed all along the area. David Moffat settled on Rollins Pass for the tunnel site but decided first to put a temporary line over the top.

Thus, in the summer of 1903, a formal contract was let for work up and over the Pass itself. By 1904, the workers reached Arrowhead and they also built a work station on top, called Corona Station, or "crown of the mountain." This railroad construction town of Corona, located at over 11,600 feet at the top of Rollins Pass (first called Boulder Pass) along the Continental Divide was the highest railroad station in the world. It became obvious by 1905 that the Corona area would require snowsheds if trains were to travel, even irregularly, during the winter. Still, word got out of the spectacular splendor of Rollins Pass and tourists flocked in on summer train excursions, sometimes stopping on top, sometimes going as far as Arrow.

In 1913, a fine hotel was built next to the rail facilities. Because Rollins Pass was right in the middle of severe weather patterns, a weather station was built on top, as well as one down at Sunnyside. In 1915, Rollins Pass was actually proposed to be the south boundary of a proposed "Estes National Park." Later, on the National Historic Register, the district was listed in 1997 as the Denver, Northwestern and Pacific Railway Historic District--Rollinsville & Middle Park Wagon Road. It was also identified as the Rollinsville and Middle Park Wagon Road; Boulder Wagon Road, Rollins Pass, and Rollinsville area. In 1956, Governor Steve McNichols had presided at the official re-opening of the four percent grade to vehicle traffic over Corona Pass, expressing the hope that the route would someday be paved. The Colorado Game and Fish Department and the U.S. Forest Service made additional improvements, and the Arapaho and Roosevelt National Forests put out a 24-page booklet titled "The Moffat Road: A Self-Guiding Auto Tour."

The road crossed two of the original railroad trestles near Corona but those trestles, even if reached by 4-wheel vehicles, were crumbling and could no longer even be crossed safely on foot. The current self-guided auto tour refers to Rollins Pass, as well as the Moffat Road and the Boulder Wagon Road. Corona Station and Hotel are discussed. In 1979, a portion of the auto road over Corona Pass was permanently closed because of a cave-in of the "Needle's Eye," a tunnel located before the trestles heading west from the Moffat Tunnel's East Portal. The tunnel reopened on July 3, 1988, thanks to efforts of the Rollins Pass Restoration Association on both sides of the Divide, with the cooperation of the U.S. Forest Service, Colorado History Society, and Boulder, Grand, and Gilpin Counties. It then closed once more when another rockfall hit the tunnel on July 15, 1990. The RPRA is continuing its efforts for re-opening. The noted photographer, Charles McClure, took many outstanding photos of the Rollins Pass road.

One, titled "Group on Rollins Pass, shows well-dressed men and women stand on a snowfield making snowballs on Rollins Pass, Moffat Road, Boulder or Grand County, Colorado; probably on Denver, Northwestern and Pacific excursion train. Date: between 1904 and 1913 near Corona Station." Another photo shows a "30 ft. snowcut on Rollins Pass, Moffat Road photo. Denver and Salt Lake Arrow passenger car is parked east of Corona snowshed by the thirty foot snowbank cut, Rollins Pass, Colorado; it shows men, women and railroad employees posed behind train, on the roof and on the snowbank and a standard gauge track. Date: between 1904 and 1915." A sign at the highway turn onto the Moffat roadbed says: The Moffat Road "Hill Route" Also called "Corona Pass Road", this road over the Continental Divide was the original "Hill Route" of the Denver, Northwestern & Pacific Railway built by David H. Moffat in 1903. It crosses Rollins Pass at 11,666 feet elevation. On top of Rollins Pass, a sign says: Elevation 11, 660 feet, John Quincy Adams Rollins established a toll wagon road through this pass in the mid 1870's. David H. Moffat's Denver, Northwestern & Pacific Railway crossed the Continental Divide at this point in 1903.

First known as Boulder Pass, then Rollins Pass, the railroad workers dubbed it "Corona", the crown of the "Top of the world." A railroad station, hotel, restaurant and workers' quarters existed here until 1928 when the railroad was abandoned due to the building of the Moffat Tunnel. Identifications in various trail and geographical guides say: Rollins Pass (el. 11,680 ft) is a high mountain pass in the Rocky Mountains of north-central Colorado in the United States. The pass is located on the continental divide at the crest of the Front Range southwest of Boulder, at the boundary of Grand County, Colorado and Boulder County, Colorado. Rollins Pass (a.k.a. Corona Pass) sits approximately 5 miles east and above the popular ski areas around Winter Park, between Winter Park and Rollinsville. The pass is traversed by an unpaved road, mostly the former roadbed of the Denver and Salt Lake Railway which abandoned the route in 1928 when the Moffat Tunnel opened to replace it. Railroad advertising called this the "Top O' the World" and it referred to the Moffat Route over the continental divide and the Rocky Mountains. Rollins Pass was the primary travel route west from Denver until an easier road over Berthoud Pass was constructed. The Denver, Northwestern and Pacific railroad laid its tracks across the pass in 1903-1904 and established a Depot at Corona on the crest. It can be noted that in R.C. Black's Island in the Rockies, the term "Corona Pass" was mentioned one time, on p. 351; the terms "Corona Station" or "Corona Snowsheds were used. In Dismantling the Rails That Climbed, Rollins Pass was used, the Corona hotel, and just once, Corona Pass; 1936.

In Maggie By My Side, it was Boulder Pass and Rollins Pass. In Rails that Climbed, Rollins Pass, the Corona shed, weather at Corona, Rollins Pass Snow Shed, other references to Corona as a site. In Guide to the Colorado Mountains (Orme) , they speak of the Corona Trail to Rollins Pass. High Country Names (Ward) used Rollins Pass entirely. Only Hiking Grand County, Colorado, published 2002 by Carr speaks of Corona Pass, with reference to Rollins Pass (near the town of Corona), Moffat Road. The term "town" might be questionable; there was only a small restaurant, workers quarters, railroad offices, and in 1913, the hotel. Current maps, USFS and the Grand County Trail Map, show Rollins Pass, with Corona at the side as being a site. The use of "Corona Pass' seems to be a rather recent innovation that has come into being with tourism efforts in the upper Fraser Valley. Rollins Pass From Island in the Rockies p. 45 Rollins Pass was originally known as Boulder Pass, first recorded being crossed by whites, by Capt. Jacob Bonesteel in April 1862. Their supplies were carried in wagons. A second organized party went over the same pass in 1865. In 1866, promoters of access into Grand County brought many wagons and livestock over Boulder Pass.In 1867, Samuel Bowles and a group returned home to Denver via Boulder Pass. In 1873-74, two roads were proposed into the county, one of Berthouds pass and one over Boulder Pass. This was the same time that the county was named "Grand". J..A Rollins and his associates started the road and reached the top of the pass in 1873, at which time they envisaged a road from HSS into Utah. The first wagons went over in June 1874. The western descent was so bad that it never was much patronized by wheeled vehicles, instead becoming primarily used for trailing of cattle. At this time the name Boulder Pass disappeared from maps and Rollins Pass became the official name. p. 85. p. 80 Lots of schemes to build roads into GC, but of all the schemes for transport, only one, the Rollinsville and Middle Park Wagon Road showed any promise. T

hat was designed by John Quincy Adams Rollins, from NH, a gifted promoter, a son of a clergyman, second of 19 children. He was a farmer, miner, freighter, road bulder, and platter of towns. He was perhaps the most accomplished billiard player west of the Mississippi. He was a Colorado resident at least by 1866. His finances were up and down, but he was tremendously strong. In December 1884, when he was 68, he thought nothing of a 3-day snow-clogged crossing of the Continental Divide. p. 85 Rollins was interested in MP as an investor and he was interested in extending his road into Utah.. At the same time, a Porter M. Smart was likewise excited about speculating in frontier projects and was working at developing the valley of the Middle Yampa. William N. Byers was busy planning for HSS. These three men launched at least two petitions, with more than 80 "residents" for creating GC. Grand County was created that year, 1874. p. 89 With the creation of GC, people began to consider the area more seriously. p. 92 There was no official mail into the county until 1873 when Rollins brought in the first US pouch over his pass. In May 1874, he built a commodious hotel at the confluence of Crooked Creek and the Fraser, known as the Junction House. p. 94 Rollins knew that the road over Berthoud Pass was superior to Rollins Pass; his main advantage was the railhead at Blackhawk.

So Rollins proposed a joint ownership and operation of the two roads for the line between Junction Ranch and HSS. Tickets would be issued for both routes and revenues would be shared. The two companies would build a bridge across the Grand at HSS. Rollins even complimented the Berthoud work. This merger was completed soon. p. 104 This bridge was started in November 1874. p. 108 A mail contract was made in July 1875 for once a week delivery over Rollins Pass, but conditions were so severe that the route was changed to Berthoud Pass. p. 110 From the beginning, Rollins Pass was used in preference to Berthoud Pass for trailing livestock, because there were fewer problems with timber and bogs. However, late spring snowdrifts were a problem, so 20-30 horses were often brought along to break trail. The Church brothers, ?George and John, summered their cattle in what became known as Church Park and dug the Church Ditch. They also introduced the celebrated Hereford breed into GC. p. 170-171 As interest in bringing a railroad into and through GC developed, about 1880, various stockholders proposed to build up South Boulder Canyon to Yankee Doodle Lake and start a tunnel near Rollins Pass. Nothing came of the first attempts but by the end of July 1881, numerous surveys had been made for that tunnel. p. 238 Cattle was still being trailed out via Rollins Pass up to the turn of the century. p. 258 David Moffat and Horace Sumner, his chief engineer, in the fall of 1903, were planning the tunnel for future excavation; but in the meantime a temporary line was planned for crissing Rollins Pass, at 11,640 feet. p. 264 A formal contract was let for the work over Rollins Pass in August 1903. The loftiest sections were started first, and the first cuts at the top were nearly finished by the 26th of October and tunneling started at Riflesight Notch. As snow came, work slowed to a standstill. p. 265 Work in 1904 was extremely slow until the end of August.

An encampment was built at Arrowhead and a station at the crest of the Divide was named Corona Station, where long snow sheds were built almost immediately. p. 267 Arrowhead was soon shortened to Arrow, when a post office was opened there in 1905. Travel on the grades, at 4-5% grades up over Rollins Pass was exceedingly difficult. p. 270 In 1908, word of the scenic splendor of Rollins Pass was becoming known world wide. Also, Rollins Pass and its "Corona station" were attracting the attention fo the US Weather Bureau, for the pass lay squarely in the center of the region of heaviest snowfall on the entire Colorado Continental Divide. p. 344 A terrible winter in 1909 made people think that Rollins Pass was never going to be practical for the long term. Time and again freight and passengers were stuck on top at the Corona facility. In 1913, a $10,000 hotel was built at Corona next to the rail facilities. From Dismantling the Rails That Climbed p. 6 The railroad went from Denver to the top of Rollins Pass. p. 8 Snowsheds were built over the tracks at Corona and other strategic places in 1905. p. 12 The top was referred to as "Corona Pass" 1936. p. 16 Crews who were to removed tails and ties reached Corona at the top of Rollins Pass 1936. p. 20 Reference to the Corona hotel From Maggie By My Side p. 1 Jimmy Crawford heard that a man named John Quincy Adams Rollins was building a road over the range at a place called Boulder Pass. 1873 p. 9-14 June 1874 The Crawford family traveled to Rollinsville and then to Yankee Doodle Lake, where the road ended. Rollins' men were still hacking the road out of the granite. Jimmy and his crew helped. On the morning of June 10, the family started out to go over the rocks and up the mountain. Then he borrowed two yokes of oxen to his wagon, then mules, then his horse. The animals had to rest every few feet; the family climbed on foot. There was no shelter at the top. Rollins' men had done no work yet on the west side of the pass except to cut a rough swath down through the trees. The road dropped down along Ranch Creek. From Rails That Climb published 1950 p. 43 Leyden Junction to Tolland to Rollins Pass. P. 63-64 Many references to Tunnels as identifiers of location. p. 76-77, 78 reference to the old Rollins Pass toll road; first mention of the place called Corona- crown of the mountain. Most references are to Rollins Pass. The Corona shed is mentioned, p. 82. p. 83 Sunnyside water stop, Loop Trestle and Tunnel, Ranch Creek Trestle and water stop, Arrow. p. 95, 100- 101 It is eleven miles from Arrowhead to Rollins Pass. Rollins Pass-Boulder wagon road; other references p. 107 - 112 reference to Corona shed. Reference to pipe line to Corona; a number of comments to Rollins Pass p. 119 weather at Corona p. 120-121 Rollins Pass p. 151 Rollins Pass p. 182 photo of "Rollins Pass Snow Shed" "This Corona station burned one night." p. 188 photo of June at Rollins Pass p. 192-194 photos of Corona shed and other buildings; Rollins Pass p. 252 walking on top of snow shed at Corona p. 271- 272. 1910 Snowshed at Corona p. 312-314 Rollins Pass; Rollins Pass snowshed; Corona; Corona siding p. 324 Corona; Sunnyside weather report station p. 326 Corona sheds p. 333-335 Corona shed; references to "Corona" as a place From Guide to the Colorado Mountains published 1974 p. 54-55 Corona Trail, going from East Portal to Rollins Pass From High Country Names published 1972 p. 105 Irving Hale in 1878 drove his wagon over Rollins Pass, now nearly abandoned as a wagon road. p. 131 David Moffat decides to build a temporary line over Rollins Pass. p. 165 In 1915, Rollins Pass was proposed to be the south boundary of a proposed "Estes National Park". From Hiking Grand County, Colorado published 2002 p. 52 Trailhead on the "Moffat Road to Corona Pass". In same paragraph, it becomes Rollins Pass (near the town of Corona). On p. 54, reference to the Corona Road. On p. 57, map shows Rollins Pass with Corona marked as a "site." p. 56, reference to the old railroad bed used crossing the Divide at Rollins Pass, near the town of Corona.

Sometimes called Corona Pass. p. 60-61 Rollins Pass Wagon Road historical notes on JQA Rollins and how to find his wagon road over Rollins Pass, following Ranch Creek to Tabernash. p. 66 Rollins Pass (Corona) to Devil's Thumb From GCHA Journal The Journey p. 6 Rollins Pass used by Indians; comment in 1981 From GCHA Journal Middle Park Indians to 1881 p. 8 Archaic hunters camped in the Rollins Pass area; written mid-1970's The current maps, USFS and Grand County Trail Map, show Rollins Pass with Corona at the side as being a site. The Rollins Pass Restoration Association for many years, and currently, has been trying to open the road and Needles Eye Tunnel. The self-guided auto tour refers to Rollins Pass, as well as the Moffat Road and the Boulder Wagon Road. Corona Station and Hotel are discussed. On the National Historic Register Denver, Northwestern and Pacific Railway Historic District--Rollinsville & Middle Park Wagon Road (Boundary Increase) ** (added 1997 - District - #97001114) Also known as Rollinsville and Middle Park Wagon Road;Boulder Wagon Road;R Rollins Pass, Rollinsville Corona Station and Hotel The railroad construction town of Corona, Colorado, located at over 11,600 feet at the top Corona Pass (first called Boulder Pass) along the Continental Divide was the highest railroad station in the world. It was situated on an old Native American trail, the same trail it is believed the Mormons traveled on their way to Utah. The road was improved by the U.S. Army, then further improved in 1866 by General John Q. Rollins, for whom the pass and the town of Rollinsville were officially named. Because of the high drifts of snow, the pass was only open from around July to the first big snowstorm two or three months later. In 1956, Governor Steve McNichols presided at the official re-opening of the four percent grade to vehicle traffic over Corona Pass, expressing the hope that the route would someday be paved. The Colorado Game and Fish Department and the U.S. Forest Service made additional improvements, and the Arapaho and Roosevelt National Forests put out a 24-page booklet titled "The Moffat Road: A Self-Guiding Auto Tour."

The road crossed two of the original railroad trestles near Corona but those trestles, even if reached by 4-wheel vehicles, are crumbling and can no longer even be crossed safely on foot. In 1979, a portion of the auto road over Corona Pass was permanently closed because of a cave-in of the "Needle's Eye," a tunnel that came before the trestles on a westward drive from the Moffat Tunnel's East Portal area. The tunnel reopened on July 3, 1988, thanks to the efforts of the Rollins Pass Restoration Association with the cooperation of the U.S. Forest Service, Colorado History Society, and Boulder, Grand, and Gilpin Counties. It was then closed once more when another rockfall hit the tunnel on July 15, 1990. John K. Aldrich is a geologist, lecturer, and author whose "Ghosts of . . . " books and accompanying topo maps are a boon to hobbyists, explorers, and those interested in Colorado mining history. Date: 02/04/08 05:13 Rollins Pass Milepost 16 Corona Station. Picture 6 below, is DPL photo X-7388. "Title: Corona, Colorado, interior of snowshed. Summary: Passengers stand next to the covered train depot at Rollins Pass, in Corona (Grand County), Colorado. The tracks of the Denver, Northwestern & Pacific Railway are in the foreground. The depot is constructed of logs, and the roof of the snowshed is upheld by timbers. Sunlight streams through the opening at the end of the snowshed. Date: (between 1904 and 1913). Source: E. T. Bollinger from W. I. Hoklas." Picture 7 below, is DPL photo MCC-454A. "Title: Group on Rollins Pass. Summary: Well dressed men and women stand on a snowfield making snowballs, Rollins Pass, Moffat Road, Boulder or Grand County, Colorado; probably on Denver, Northwestern and Pacific excursion train. Date: (between 1904 and 1913). Creator: Louis Charles McClure 1867-1957. Picture 8 below, is DPL photo MCC-624. "Title: 30 ft. snowcut, Rollins Pass, Moffat Road photo. Summary: Denver and Salt Lake Arrow Turn (passenger car) parked east of Corona snowshed by thirty foot snowbank cut, Rollins Pass, Colorado; shows men, women and railroad employees posed behind train, on roof and on snowbank and standard gauge track. Date: (between 1904 and 1915 The highway sign says The Moffat Road "Hill Route" Also called "Corona Pass Road", this road over the Continental Divide was the original "Hill Route" of the Denver, Northwestern & Pacific Railway built by David H. Moffat in 1903. It crosses Rollins Pass at 11,666 feet elevation. On top of Rollins Pass, a sign says: Rollins Pass Elevation 11, 660 feet John Quincy Adams Rollins established a toll wagon road through this pass in the mid 1860-s. David H. Moffat's Denver, Northwestern & Pacific Railway crossed the Continental Divide at this point in 1903. First known as Boulder Pass, then Rollins Pass, the railroad workers dubbed it "Corona", the crown of the "Top of the world." A railroad station, hotel, restaurant and workers' quarters existed here until 1928 when the railroad was abandoned due to the building of the Moffat Tunnel. Rollins Pass Elevation 11,680 ft (3,560.1 m) Traversed by Unpaved road Location Boulder_County,_Colorado / Grand,Colorado Rollins Pass (el. 11,680 ft) is a high mountain pass in the Rocky Mountains of north-central Colorado in the United States. The pass is located on the continental divide at the crest of the Front Range southwest of Boulder at the boundary of Grand_County,_Colorado and Boulder County. Sign that sits on top of Rollins Pass Rollins Pass (a.k.a. Corona Pass) sits approximately 5 miles east and above the popular ski areas around Winter Park, between Winter Park and Rollinsville. The pass is traversed by an unpaved road, mostly the former roadbed of the Denver and Salt Lake RailwayDenver_and_Salt_Lake_Railway which abandoned the route in 1928 when the Moffat Tunnel opened to replace it. Rollins Pass Railroad advertising called this the "Top 'O the World" and it referred to the Moffat Route over the continental divide and the Rocky Mountains. Rollins Pass was the primary travel route west from Denver until an easier road over Berthoud Pass was constructed. The Denver, Northwestern and Pacific railroad laid its tracks across the pass in 1903-1904 and established a Depot at Corona on the crest. David Moffat planned to replace the "Hill Line" with a tunnel through James Peak within a few years of the railroad construction. However, he never could obtain financing for the tunnel due to the inability of the railroad to make a profit and opposition from competing railroads such as the Denver and Rio Grande. The D&RG saw the line as a threat. But, in the far future the construction of Moffat Tunnel would turn out to be the D&RG's saving grace.

The trip up Rollins Pass was a favorite of summer tourists looking to enjoy the mountain scenery. It was heavily promoted by the railroad with picnic and wildflower picking excursions. Sights along the line were made famous by postcards containing the photos of L. C. McClure. At last the route surmounts the crest of the Continental Divide and takes quick refuge on the top at Corona. At elevation 11, 660 this is truly the famous Top O' the World and one of the highest railroad passes in the world. Due to the great height and nature of the Rocky Mountains, the entire railroad complex was completely enclosed in giant covered snow sheds.

,

,

,

,  ,

,