Skiing

Skiing Articles

| Arapahoe Ski Lodge |

Arapahoe Ski Lodge

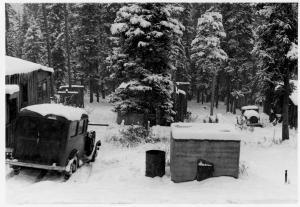

Article contributed by Chris Tracy, Courtesy of Alpenglow Magazine 2009 The Arapahoe Lodge's history has everything to do with a perfect ski vacation experience. 2009 celebrates the lodge's 35th anniversary. Rich and Mil Holzwarth and their children (now adults) Jan and husband, Greg Roman, Brad and Todd have lovingly operated the Arapahoe Ski Lodge since 1974. That was before there were sidewalks and street lights- when the town was still named Hideaway Park. It was before Mary Jane, and snowboards, when a day of skiing at Winter Park Ski Area was $7.50; when old Ski Idlewild boasted a $6 lift ticket; and lessons at both resorts cost a whopping $8. It was before snowmaking equipment allowed the resort to open early, and when phone calls still went through a friendly local switchboard operator, and calling Granby from Winter Park was long distance. "Our number at the lodge then was Winter Park 8222," Jan recalls. Other ski lodges in operation included Idlewild Lodge, Timberhouse, Beaver Lodge, High Country Inn, Woodspur, High Forest Inn, Yodel Inn, Sitzmark, Miller's Idlewild Inn, Brookside, Winter Haven Lodge, Tally Ho, Outpost Inn, and Devil's Thumb. Like the Arapahoe, most had a bar, sauna and hot tub. Now, only a few of the grand old lodges remain. Condos and hotels have taken their place, and guests who frequent them unknowingly sacrifice a romantic, unique experience only a ski lodge can offer.

|

| Barney & Margaret McLean |

Barney & Margaret McLean

It was the spring of 1924 when an 8-year-old girl from Hot Springs, Ark., arrived in Hot Sulphur Springs by train to spend the summer with her aunt and uncle Hattie and Omar Qualls, homesteaders from Parshall who had recently purchased the Riverside Hotel. It wasn't the first time Margaret Wilson had been to Hot Sulphur. Her father had tuberculosis and was frequently prescribed treatment at the sanatorium on the Front Range. She was 6 years old the first time she made the train trip.

Hot Sulphur had four ski hills back then and Margaret recalls that in February 1936 the Rocky Mountain News sponsored an excursion train to the 25th Annual Winter Carnival in Hot Sulphur. More than 2,000 passengers arrived on three trains that weekend. (That same train later became the official ski train. |

| Railroads Build the Ski Industry |

Railroads Build the Ski Industry

In the early to mid-1900s, the popularity of skiing spread across the western United States. Ski areas popped up in many mountain communities, particularly in the Colorado Rockies. Much of this was due to access afforded by the existence of railroads to these areas. Railroads broke the barriers of isolation during the winter months when most other forms of transportation were blocked (skiing being the exception). Grand County has long depended on tourism. From its earliest days of settlement, tourists were drawn to the springs of Hot Sulphur Springs and to the waters of Grand Lake and its surrounding streams. Grand County was reached by stagecoach from Georgetown, via the Berthoud Pass Wagon Road. In the summer months tourists would fill up Hot Sulphur Springs’ five hotels. Nonetheless, those same hotels would sit mostly vacant during the long winter months when the road was shutdown.

In 1911, Hot Sulphur Springs held the first winter sports carnival west of the Mississippi River. The purpose of the carnival was to boost the town’s economy by filling the empty hotels and restaurants with out of town guests for that one weekend at the end of December. This was only possible due to the Moffat Road railroad, which had broken the town’s isolation just six years prior.

Not only did the railroad bring spectators for the winter carnival, it also brought the two most important participants of the event. At least, it brought them part way. Carl Howelsen and Angell Schmidt boarded the train in Denver’s Moffat Station and rode it to the top of the divide at Corona, where they detrained and skied the rest of the 40-plus miles to Hot Sulphur Springs, where the carnival was under way. Once re-united with their fellow train passengers, Howelsen and Schmidt performed the biggest event of the day, the ski jump competition, which made history. The ski jump competition at the 1911 Hot Sulphur Springs Winter Sports Carnival was the first west of the Mississippi and is considered the beginning of Colorado’s ski industry.

The 1911 winter carnival was such a successful and enjoyable event that it grabbed the attention of Denver newspapers on the front pages. Consequently, John Peyer and the other carnival organizers of the carnival decided to make it an annual event and put together the 1st Annual Hot Sulphur Springs Winter Sports Carnival six weeks later in February 1912. The railroad was the sole reason that the success of the winter carnival at Hot Sulphur Springs was even a possibility in those early years. Berthoud Pass, the former wagon road converted to an auto route was closed in the winter months. Even if the highway were open, automobiles of that day could not have made the winter drive anyway. The railroad was the only way to bring people to the remote town in the winter and take advantage of the abundantly snowy hills.

The Moffat Road quickly realized the potential for profit that the Hot Sulphur Springs Winter Carnival presented in the typically slow winter months of the railroad. In 1913, the Denver and Salt Lake Railway (D&SLR) advertised a special round trip fare to Hot Sulphur for the winter carnival. The following year, further up the Moffat Road, Steamboat Springs held its first winter carnival.. Once again, the D&SLR provided the means to reach the new ski destination. People road the rails from Denver and Hot Sulphur Springs.

As the popularity of Hot Sulphur Springs as a winter destination grew, so did ridership of the D&SLR to the winter carnival. In 1936, the Rocky Mountain News sponsored the “Snow Train” to Hot Sulphur Springs for the 25th anniversary of the winter carnival. Despite the fact that Berthoud Pass was open year round starting in 1933, over 2,200 passengers rode the ironhorse from Denver and another 500 came over the Moffat Road from Steamboat Springs for the event. Over 7,000 people attended the carnival that weekend.

In the early years of the ski industry, Nordic was the dominant form of skiing. By the late 1920s, Alpine skiing began to grow by leaps and bounds in the United States. This coincided with the opening of the Moffat Tunnel, which made the railroad far more reliable in the winter time. It would be at the west portal (West Portal) that the railroad would make its biggest impact on skiing in Colorado. Following the opening of the Moffat Tunnel, skiers would ride up to West Portal from Denver to slide the deep and steep slopes immediately adjacent of the tunnel. Not long after the opening of the tunnel, the Arlberg Club was formed and they built their clubhouse not for from the tunnel to take advantage of the rails from Denver to the slopes on the west side of the divide.

Arlberg Club members and other ski enthusiasts flocked to West Portal by rail throughout the 1930s, even though there was no formal ski area. Skiing and riding the train to West Portal was so popular that in 1938 the D&SLR started the “Snow Train,” offering regular weekend service to West Portal. The D&SLR even provided a place for skiers to wax their skis in the West Portal Depot.

The start of the Snow Train coincided with decision of Denver Parks Director, George Cranmer’s decision to locate Denver’s Winter Park at West Portal. Cranmer announced his intention of creating for Denver a winter sports playground that would be “unequalled in the world. When he determined that West Portal would be the location for Denver’s Winter Park he referenced the great ski conditions of the area and additionally remarked that “West Portal may be reached by auto or train.” Cranmer clearly recognized the importance of access by train from Denver.

As ski trails were cut and T-bars were installed on the mountainside the base area facilities for Winter Park were literally constructed on the tailings of the Moffat Tunnel. This provided easy access to the facilities and slopes of the ambitious new ski area for those riding the train from Denver. The D&SLR continued to provide the Snow Train weekend service when Winter Park opened in 1940 for $1.75 per round trip. Unfortunately, due to the demands of World War II and a coal workers strike in 1943, the Snow Train service came to an end. This would prove to be temporary though. In 1946, one year after the end of World War II, the Denver and Rio Grande Western (D&RGW) brought the special weekend service back to Winter Park and christened it as the “Ski Train.” This was the foundation of the Ski Train that ran between Denver and Winter Park until 2009.

Grand County was not the only ski destination that benefitted from the railroads in the early growth years of the ski industry in the west. A couple of major examples are Marshall Pass in Colorado and Sun Valley, Idaho. Beginning in 1938, the D&RGW literally acted as a chairlift for skiers from Salida and Gunnison. A special excursion train on the weekends selling seats as lift tickets to the top of Marshall Pass. The first train sold out with 500 tickets and 200 skiers were turned away that day. The railroad even provided a warming hut at the bottom of the slopes.

In possibly the greatest example of the railroad on the ski industry of the west is Sun Valley, Idaho and the Union Pacific Railroad (UP). Sun Valley was literally the conceived, constructed, and operated by the UP. Under the leadership of Averill Harriman, who was a ski enthusiast himself, conjured up the plan to build a world class ski destination that would rival any in Europe. This resort was to be reached by rail as a means to boost ridership on the UP, which it did. Sun Valley became the glamorous playground for the rich and famous. At Sun Valley, skiing was elevated in class and viewed as elite. Nonetheless, it was at Sun Valley that the railroad made its most significant contribution to the ski industry. The first chairlifts in the world were installed at Sun Valley in 1936, replacing the rope tow. Engineers for the UP developed the chairlift at the railroad’s headquarters in Omaha. The invention of the chairlift transformed the method of how skiers were to be transported to the top of ski trails the world over.

The impact of the railroads on the development of the ski industry in the western United States cannot be understated. Without the assistance of the network of steel that penetrated into remote mountain locations, the ski industry could not have developed with the rapidity that it did in the early part of the 20th century. Furthermore, as we look to the future of the ski industry and try and figure out ways to conveniently transport skiers to the slopes of Colorado trains emerge more and more as the answer. This is apparent in the rejoice that devotees to Winter Park sang when Amtrak’s Winter Park Express returned weekend service in 2017 that had been left in a void ever since the Ski Train made its last run in 2009. Once again skiers are riding the rails of the old Moffat Road.

|

| Skiing |

Skiing

Grand County was one of the first areas in Colorado to enjoy sport skiing. While mail carriers, loggers and other workers used the "Norwegian Snowshoes" as necessary winter transportation, it was a natural progression to begin racing down the slopes for fun. An 1883 newspaper noted that in Grand Lake "Coasting on snowshoes has taken the place of dancing parties. Quite a number of ladies are becoming adept at the art. First class snowshoers, B.W. Tower and Max James are the best; or at least they can fall more gracefully then the rest". According to famous Hot Sulphur Springs champion Barney McLean, that town had three jumping hills in the 1920s and held the first Winter Carnival in the West there in 1911. By 1925, Denver sent special "snow trains" there for the recreating tourists. Skiers such as Bob McQueary and Jim Harsh competed in statewide events along with skiing "veterans" Horace Button and McLean. Grand Lake's Jim Harsh became the first Coloradoan to qualify for the U.S. Olympic Team. In 1932, the Grand Lake Ski Club held its first winter sports week on Denver 25-January 1st. Featured was a motor sled with an airplane engine which pulled skiers over the frozen lake are speeds of 90 miles per hour. Colorado's first ski tow was opened at the summit of Berthoud Pass in 1936. Berthoud Pass operated on and off throughout the next 60+ years but was finally closed and the lifts dismantled in 2002. What became the resort of Winter Park featured skiing at the West Portal of the Moffatt Tunnel and the Winter Park Ski Area opened as a result of efforts by Denver Parks & Recreation Director George Cranmer. Early lodging resorts in the area, then known as Hideaway Park (now Winter Park), included Sportland Valley, Timberhaus Lodge, and Millers Idlewild Inn. Eventually trains made daily runs to Winter Park, loaded with intrepid skiers. Steve Bradley invented the first effective snow packer on the slopes of Winter Park. With a strong record of winning high school ski teams, Grand County accounted for a remarkable number of skiers who later took park in FIS (International Federation of Skiers) meets and U.S. Olympic teams. |

| The Millers Build Idlewild |

The Millers Build Idlewild

Article contributed by Jean Miller In June 1946, the C.D. Miller family broke ground for Idlewild Inn in the small village of Hideaway Park, Colorado. Although WWII was over, materials were still very scarce. What could be obtained locally was bought. Much was brought from Wichita, Kansas, where the family lived. By 1948, the rustic Inn was up and running. It had the charm that comes with the scent of pine wood, cozy fires, hearty food, friendly hosts, and total relaxation. Sons Elwood and Dwight managed the business, with the vital assistance of parents and friends during the Christmas season and summers. Elwood married after graduating from college and bit by bit, he gravitated to the teaching world, leaving Dwight to deal with eager guests. Idlewild Inn became a popular spot, especially families for seeking simple vacations. However, after a few years, the Millers realized that there was developing a desire for more sophisticated lodgings. About 1952, Dwight and his bride Jean had the opportunity to buy 160 acres of land across the valley, to which was later added 40 acres from a mining claim. The price was $10,000 and the couple wondered how they ever would pay for it. Nevertheless, this chance was too good to miss. The property extended far into what is the main portion of town today, across the railroad, and along both the Fraser and Vasquez Creek. A pleasant lane wound through the forest from the highway to the creeks and broad meadow. One step led to another. Dwight chose one-of-a-kind heavy, 4 foot thick cedar planks for the walls of his new lodge. He nestled the building into the "vee" of the valley flowing down behind. By Christmas 1957, Dwight and Jean opened by far the finest lodge in the area. Each bedroom had two double beds and a private bath with ceramic tile, a first in the area. The first full bar in the lodge was much appreciated by guests on cold nights. A few years later, Dwight built a year-round outdoor swimming pool, the first in the county. (It took as much coal to heat the pool as to heat the lodge itself.) Guests loved it, for in winter, they came from a day of skiing, jumped into the pool for a swim, ran to the steam room (also a first), and finally took a snooze before evening festivities began. Dwight was the first in the area to use a school bus for transportation to and from the ski area and in summer, to take people on trips within and out of the county. The realization grew that a beginners' area close at hand would be a great attraction, especially for mothers who found the trails at Winter Park daunting. They could bring their children to Ski Idlewild to learn to ski, brush up on their own skiing, and when tired, go into the lodge to relax or swim. It took all of two weeks to decide on a Pomagowski double chairlift. That summer slopes were cleared and groomed, the lift and warming house built, and the area opened in 1960, two years before Winter Park had its first chair lift. Dwight and Jean even had a fine neon sign at the entry off the highway, one more first. Saturday races, sponsored by Ski Idlewild and George/Hazel Ferris's Mountain Shop drew droves of youngsters. About 1961, Dwight introduced ski bicycles, which were hugely popular. He also started using the first snowmobile for grooming and first aid purposes in the area. In the meanwhile, Jean was identifying snowshoe and cross-country ski trails through the nearby back country. By 1964, their thoughts were turning to snowmaking, to enhance early skiing. To this day, people will walk up to the Millers and say, "Oh, Ski Idlewild! I learned to ski there! Loved it." As for summer activities, trips to areas of interest, swimming, and horseback rides were standbys. In addition, the Millers built a small golf course in the meadow and a trout pond at the bridge, which they stocked. As the Miller children grew, Dwight and Jean found that they wished for more family time together, and when an opportunity to sell the property came along in 1965, they gave up what was a flourishing, solid, and very profitable business, moving to Tabernash to try other challenges. Unfortunately, the new owner was not a good steward and Ski Idlewild gradually d clined. An era of exciting innovation came to an end.

|

| Winter Carnivals |

Winter Carnivals

Carl Howelsen, a ski jumping champion in his native Norway, came to Denver to pursue a career as a stonemason in the early years of the 20th Century. He amused himself and others by demonstrating ski-jumping in the foothills of Denver. In 1911, Howelson went to Hot Sulphur Springs, where he taught locals such as Horace Button the art of jumping. Under Howelson's leadership, the first winter carnival west of the Mississippi Rover was held there on February 10-12. According to the Middle Park Times, "Never before in the history of the Territory and State of Colorado has such an event even been contemplated, much less held!". Norwegian immigrants Howelson, Angell Schmidt of Denver and Gunnar Dahles of Williams Fork (Grand County) all staged jumping competitions during the carnival. There were also skating and tobogganing events and a Grand Ball. Hot Sulphur Springs continued holding Winter Carnivals annually until World War II, when they were discontinued until the 100th anniversary celebration, called the Grand Winter Sports Carnival scheduled for December 30, 2011-February 11, 2012. |