Museums

.

Museums Articles

| Who Started the Museum? |

Who Started the Museum?

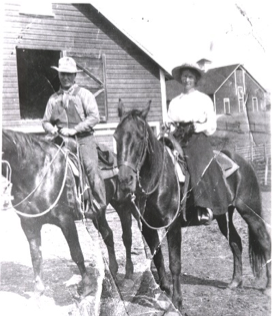

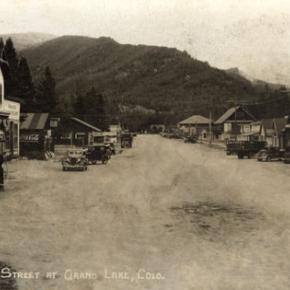

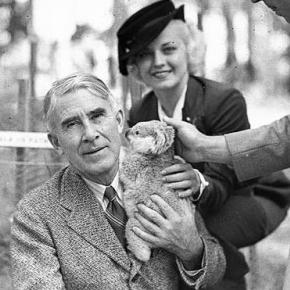

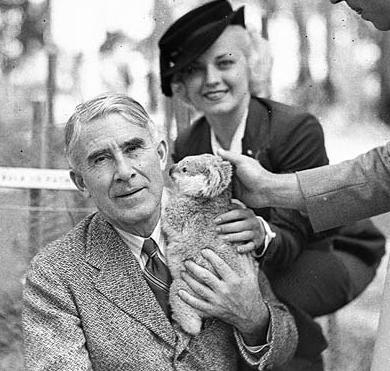

Article contributed by Jean Miller Many years ago, as in the beginning of the 20th century, the early Grand County pioneers worked, socialized, raised families, and developed sturdy towns such as Hot Sulphur Springs. Many of them gathered information about county citizens, but of all these, probably Daisy Button created the most comprehensive resource over the decades. Daisy and her brother Horace lived with their parents, Schuyler and Josephine, on a small ranch at the foot of Cottonwood Pass on the east side. Among other things, the family operated the toll gate, collecting fees from travelers going to Hot Sulphur. Eventually the Buttons moved into town and, Later, Daisy, married Charles Jenne. Daisy was one of those people who had a real feel for what information was the most useful to save for the future. She collected obituaries (one of the most valuable of all tools for historical reference). She cut out articles on politics, new businesses, town events. She kept programs, fliers, political announcements, menus, and dance cards. Then in 1919, the first and second waves of Grand County pioneers created the Pioneer Society. At first it was mostly a social group, but as the old-timers started to die off more quickly, their children realized they should start keeping records of the settlers and their doings. Who had a large and extensive set of scrapbooks, telling all about the early days, but Daisy Jenne! The original Courthouse in Hot Sulphur stood about where the County Jail is now. When the "new" Courthouse was built, the old building's space became available for the Pioneer Society to use as a museum. Daisy moved her collection of artifacts over there. Others donated household or personal articles. So the little museum came to life, with Daisy as its primary caretaker. There was a core of folks from the area who, over the years, helped her and who took over after she died. There was John Sheriff, whose mother had homesteaded on the Grand River just east of "Potato Hill", coming from Leadville after her husband died. John's wife Ida (Marte) was a key person; her family had come from Austria to homestead east of Cottonwood Pass on Eight Mile Creek. Manny Wood, part of a huge homesteading family on the Williams Fork, pitched in, along with his wife Henrietta (Bode), whose family settled on Corral Creek. And there was Paul Gilbert, long time head of the Fish and Game Dept. in the county. Paul was a fine photographer. For many years, he took photos of historical sites and people, and he also reprinted old pictures, all of this for the Pioneer Museum. If it weren't for Paul, the Grand County Museum would not be able to boast of its very excellent and extensive collection of photos today. As Colorado's Centennial Year (1976) approached, Regina Black and her husband Bob thought that there were so many newcomers who were not of pioneer stock, but who were very interested in the history of the area, perhaps a new organization could be formed to accommodate these folks. Bob had already written Island in the Rockies in 1969, published by the Pioneer Society. This book basically became the "bible" for county pioneer history. So Reggie put notices in the paper, announcing a meeting at their home, to discuss possibilities. She expected 10 or 15 people maybe. Some 60-70 showed up! The need was great. By this time, a small addition had been built at the rear of the old courthouse, to hold the Hot Sulphur Library. I was on the library board at that time. I remember well how the museum collection was growing and the library collection was growing; and we library folks kept encroaching on museum space. We never came to blows, but we thought about it! The upshot of Reggie's effort was the creation of the Grand County Historical Association, an umbrella organization intended to support all historical efforts within the county. The group sought and received a Centennial Grant that allowed them to go to the East Grand School Board and negotiate the transfer of the old school from the school district to the GCHA. I was on the school board at that time, when we closed that school for lack of students, amidst a huge amount of community flack. This seemed a good way to accomplish our purpose and also to continue helping out the community. The grant allowed GCHA to moved the old courthouse and the original jail to the new museum grounds. The Hot Sulphur library was given a tiny space in the "new" courthouse. I got involved with GCHA about this time, in 1976. The first day I went over to offer to work, I came in to find Ida and Henrietta coming up from the basement, totally covered in soot. They were scrubbing out where the old coal furnace had been, to make space suitable for storage.&n sp; I was put to making signs with press-on letters, a job I hated but did for years, until we got a computer. I never could get those pesky letters straight and evenly spaced! Reggie, Ida, Henrietta, and I formed the core exhibits committee in those early years, with John and Mannie furnishing building expertise and Paul furnishing photos. Over time, many others came to help in many ways Jean Chenoweth, Jan Catlow, Keith Nunn, and later, the George Mitchells, Larry and Jan Gross, and others. To raise money, one of our best efforts was the Buffalo Barbecue and Flea Market, a hugely successful event until others like the idea and held their own, resulting in major loss to our profits. We tried other ideas, such as house tours and silent auctions and lectures, with basically the same kind of result. What the answer is for fund raising is a mystery, for today there are so many activities going on that it is very difficult to come up with something new. The Endowment Fund is the most effective fund source as nobody else can encroach on that territory.

|

,

,