Community Life Articles

| Christmas at Fraser |

Christmas at Fraser

The lights dimmed; mothers had already found their seats after coming from the classrooms where they had put makeup on little children’s faces and checked their costumes to make sure angel wings and halos were secure and costumes were on right side round. I was at the piano, music and script lined out. The gym was full to the brim, every seat taken, with folks lining the sides and back walls, for the whole town had turned out. Early birds got the seats! Christmas wasn’t Christmas in the Fraser Valley unless it included the program at Fraser School (now the Town Hall). I began the overture and chatter stopped. I had played for this event for ages, starting in 1958. High school students were gone by then, moved to the new Union High School in Granby, but 7th and 8th graders were still there. And in 1958, the first kindergartens in the district were established. It was a time of excitement and anticipation, of fun, and of panic? Well, no, not panic, for the teachers were beautifully organized. The program was chosen during October. Each teacher had a specific job. For instance, Martha Vernon, the art teacher, did sets. Helen Hurtgen was responsible for dialog. Edith Hill did costumes. Nancy Bowlby was in charge of the music. Others coordinated the whole. And I played the piano, with Nancy sometimes accompanying me on her violin. Mothers were asked to contribute sheets and any fabric they could spare. Patterns and material for costumes went home to be sewn into various sizes and shapes -- angels, gingerbread men, knights or royalty. In the gym, we stitched on finishing touches, bright patches to decorate jester outfits, townspeople, and such, while watching various groups practice. Bits of tinsel became crowns, tinfoil turned into wands, cheesecloth into wings. Lace scraps and sequins added color and “class.” The budget was extremely minimal at first, but over the years, more money was directed to Christmas programs. Instead of old sheets, we could buy cotton fabrics, velveteens, sometimes satin. One year I even stopped by a furrier’s in Denver and begged some fur scraps. Were we uptown then! We had fur trim around the necks, cuffs, and hems of the costumes for the prince, queen, and king. The day before the play, PTA mothers gathered in the gym to fill brown paper sacks with an apple, orange, nuts, and candies, provided by R. L. Cogdell from his grocery store. Every single child in school took part in the play, as a class, except for those with speaking parts, of course. Fraser grew and grew, then as now. Soon the 7th and 8th grades moved to Granby. Then the 6th graders went, but the 4th and 5th graders handled the leads neatly. Our stories were usually simple Christmas tales, but sometimes we tackled ambitious efforts such as the Nutcracker Suite or a version of Gilbert and Sullivan. The only children not included were the Jehovah Witness youngsters. They couldn’t be in the play and they couldn’t come watch it either. We all felt very sorry for them, because everyone had such a wonderful time. Their teachers tried to give them special projects to entertain and interest them while they sat off in a corner or in their classrooms. The plays always went well. Tiny kindergartners came out onto the stage, to stand behind the colored lights. They knew their song perfectly in practices, but I have to admit that a number of them usually stood silent, stunned by that mass of faces looking up at them. No matter. They were darling. “Hi, Mom,” some were sure to call. “Mom” beamed. |

| Christmas at the Crawfords |

Christmas at the Crawfords

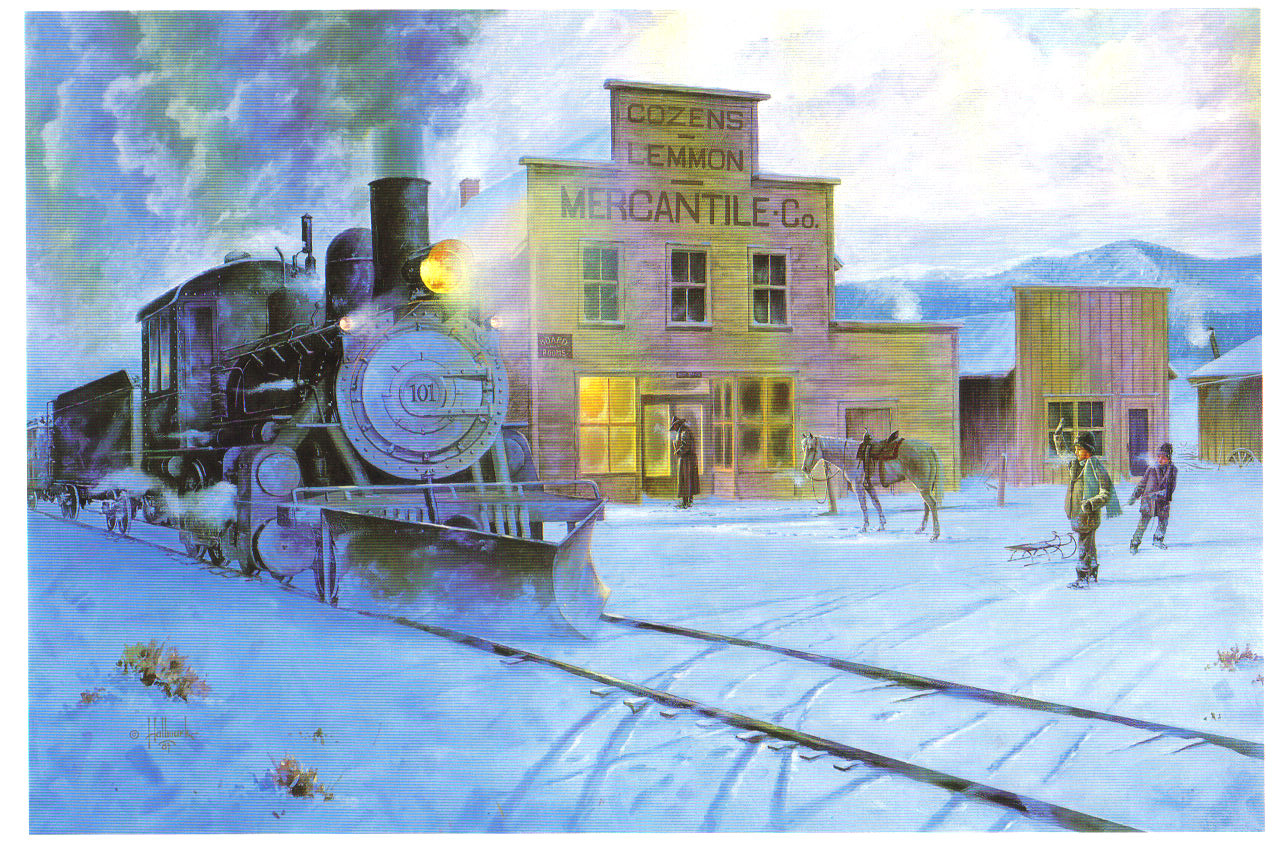

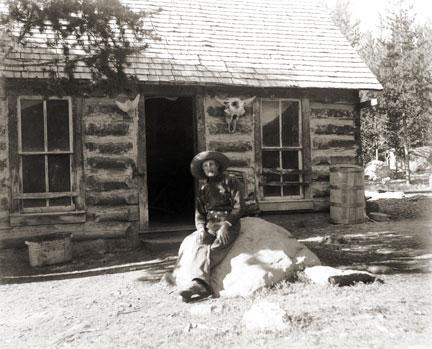

Jimmy and Maggie Crawford settled in Hot Sulphur Springs in June of 1874. They left their farm in Missouri with their three children, John not yet two, Logan 4 and Lulie 7 years old to begin a new life in Colorado. The one room cabin was built of round logs and had a sod roof. In several places outside light could be seen between the logs. The floor was packed earth covered with elk skins which had a tendency to smell while drying out after a rain or melting snow. The sod roof was far from water proof. When the children came down with scarlet fever Jimmy promised to cover the roof with wood shingles and had gone to Billy Cozens' sawmill to make them. Mr. Cozens was very helpful and even gave Jimmy a rusty iron stove to take back home. Rusty or not, to Maggie it was like new. She was most appreciative. The shingles were carefully stacked by the cabin but never made it to the roof. Jimmy carefully explored the area for suitable pasture land for his small cattle herd. His explorations took him further and further to the west of Hot Sulphur Springs and as fall approached he became desperate to locate suitable grazing pasture before the snows. Although Jimmy would return home every few weeks, the time in between his visits became longer and longer as he moved his cows to the west. Maggie was faced with many hardships in his absence. Ute Indians would quietly appear, seemingly from nowhere, and ask for food or as in one instance, ask to trade a pony for the little boy John which she of course adamantly refused. Maggie was able to keep friendly relations with the Utes but never comfortable when they appeared. The conversations were limited to jesters, hand language and a variety of facial expressions. But this is a Christmas Story. To begin with, mountain men, prospectors and just plain loafers from Georgetown would stop by the Crawford's for a meal when they were in the area. Maggie would never refuse them. A few weeks before Christmas four prospectors enjoyed a well prepared venison stew with Maggie and the three children. Lulie, the seven year old told the visitors how she was going to hang a stocking at the foot of the bed for Santa Claus to fill with toys and candy. Her two brothers shook their heads in agreement. Maggie said, "Lulie, I really don't think Santa Claus could find us way out here in Colorado!" She knew there was nothing she had to fill the stockings except maybe some sugar candy which would likely be a disappointment for each of them. Their Christmases in Missouri were memorable with presents, candies and fruit. One of the four prospectors listened intently to Lulie as she described the Crawford's last Christmas in Missouri. He had introduced himself as Charley Royer. Charley was a 22 year old, recently from Kentucky now working in the silver mines near Georgetown. After a very satisfying lunch the men left and a heavy snow began to fall. By Christmas Eve the snow was deep and drifts were high. The temperature dropped below zero. Although Jimmy had promised to be back for Christmas, Maggie thought the snow too deep for him to travel. He had located what he called the perfect pasture far to the west and had made a land claim close to a bubbling sulphur spring. He told Maggie it reminded him of the sounds steamboats made on the Missouri River and named his land claim, "Steamboat Springs." Alone with the children, Maggie read the bible story of Christmas. Before dropping off to sleep, Lulie said, "I know Santa Claus will find us, I just know he will!" Maggie sadly shook her head. Hours later, close to midnight, there was a gentle knock on the door. Maggie cautiously opened the door hoping it would not invite trouble. To her surprise it was the young Charley Royer. He held out a gunny sack and said, "Mam, I've brought some oranges, hope they haven't froze, some candy and a few toys for the children. Please tell them Santa Claus did know where they lived. I remember how important Christmas was for me and I wish you and your family a Happy Christmas." He turned and walked back into the darkness. Charley Royer had come 60 miles from Georgetown in the bitter cold and heavy snow to make three little children happy on Christmas morning with oranges no less, in the middle of winter, toys and candy, a Christmas they would never forget. Jimmy made it home on Christmas day to add to the joy. The following year and many years after the Crawfords had Christmas in a comfortable ranch house in a place called "Steamboat Springs." As for what the future held for Charley Royer, well that's a story for another time. |

| Christmas in the Mountains 1951 |

Christmas in the Mountains 1951

It was my first Christmas in the mountains. Not only that, but it was my first time to be part of a vacation in a cozy ski inn. This was at Millers Idlewild Inn in Hideaway Park (now the town of Winter Park). I had been married only eight months. Dwight and I had worked hard, getting everything in order: clean beds, fresh spreads and curtains, floors shining and bathrooms sparkling. The woodpile was full and food supplies ready. Our plans for evenings were laid out too. Dwight would do movies. His brother Woodie would call square dances, with former Moffat Road engineer George Shryer accompanying on the fiddle and his wife, Grace, chording on the piano. Tom Smith would bring his sled and team of horses, to take happy folks along snow-packed roads for sleigh rides, to the tune of jingling bells. Games were at hand, along with a fine supply of books on the shelves. We expected a wonderfully busy two weeks, which was a good thing, because it had been a long time since our last income, before Labor Day. |

| Colorado Mountain Wild Flowers |

Colorado Mountain Wild Flowers

A sight to behold A sight that will forever last Scattered among the trees Tiny little heads Oct 2006 |

| Commissioner Shootings in Grand Lake |

Commissioner Shootings in Grand Lake

Article contributed by Abbott Fay & Steve Sumrall July 4, 1883 was a tragic day of unprecedented magnitude in the history of Grand County. The booming mine town of Grand Lake had managed to move the county seat from Hot Sulphur Springs a year earlier and there was growing animosity between the “lake” and “springs” residents. On that fateful day, County Commissioners Barney Day and Edward P. Weber, supporters of Hot Sulphur Springs as the County Seat, had breakfasted with County Clerk Thomas J. Dean. As the three left the hotel beside the lake, they were ambushed by four masked men. After the smoke cleared, it was determined that the perpetrators were John Mills (the 3rd County Commissioner), Sheriff Charles Royer, Undersheriff William Redman and his brother, Mann. Day died instantly, Weber died the next morning, and Dean died from infection on July 17th. But Day fired back back, killing one of the masked assailants, who later turned out to be Commissioner Mills. The other three escaped. The sheriff and undersheriff had quickly returned to Hot Sulphur Springs and shortly after, they were sent for to investigate the very crime they, themselves had committed! Sheriff Royer shot himself on the night of the 15th and his body was discovered the next day. Dean later testified that Mills shot Weber, Redman shot Dean, Day shot Mills and Readman and Royer shot Day. Undersheriff Redman disappeared shortly thereafter, apparently shot. A body was found later on the Utah border thought to be Redman but there was no positive ID. The body was suspected to be Redman from the size of his feet. Whether he killed himself or was murdered was never determined, but nonetheless, if it was Redman, he was the sixth victim of the Grand Lake Commissioner shoot-out. It is interesting to note that all three commissioners killed had been appointed to office rather than elected. Ironically, the county seat was moved back to Hot Sulphur Springs several years later. Sources: |

| Doc Ceriani |

Doc Ceriani

Article contributed by Kathy Zeigler Dr. Ernest Ceriani was a graduate of Loyola Medical School, and served his internship at St. Luke’s Hospital in Denver. In 1942, he married a nurse, Bernetha Anderson, and joined the Navy, serving until 1946. He began a surgery residency in Denver, but was unhappy with city life, city medical practice and its politics. He came to practice in Kremmling in 1947, working for the Middle Park Hospital Association. The Association had purchased the home of the previous doctor to remodel and serve as a hospital; it employed 2 nurses as well as the young doctor. The doctor was general practitioner, seeing patients in office, hospital, and home, often as far away as Grand Lake. He was as self-sufficient as he could be, developing his own X-ray films, for example, as a cost saving measure. Medical practice for an isolated doctor was challenging. Consultation with other physicians was difficult if not impossible and keeping up with medical journals was daunting. Source: |

| Doc Susie - Mountain Pioneer Woman Doctor |

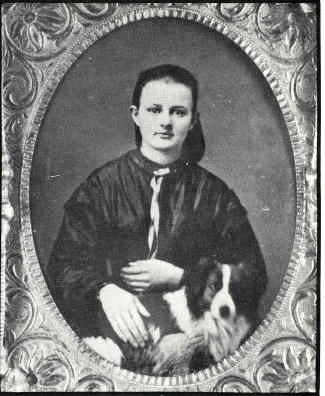

Doc Susie - Mountain Pioneer Woman Doctor

Susan Anderson was born on January 31, 1870, in Nevada Mills, Indiana. Her parents, William and Mary Anderson, were divorced in 1875. Four-year old Susan never forgot her parents arguing and her mother crying before her father literally grabbed Susan and her brother John, who was three years old, from their mother at a railroad depot. He jumped on the train as it was leaving the station and took them to Wichita, Kansas, where he homesteaded with Susan’s grandparents. Susan’s father, Pa Anderson, had always wanted to be a doctor, and he vowed that one of his children would fulfill that role, which he had been unable to accomplish. John, however, was more interested in roping cattle and playing than becoming a doctor. Contrary to John, Susie watched her father, a self-taught veterinarian, as he worked on animals. She absorbed important knowledge for her future as a physician. Susie was less interested in the lessons that her grandmother taught her: manners, housework, crocheting and cooking. Shortly after Susan and John graduated from High School in 1891, Pa Anderson remarried and became very domineering, insisting that everything be exactly as he demanded. At about the same time, the gold strike in Cripple Creek, Colorado, caught William Anderson’s attention, causing him to sell his homestead in Wichita and move the entire family to Anaconda, CO, which was about one mile south of Cripple Creek. Very rare for the time, Susan pursued an education in medicine and graduated from the University of Michigan and started practicing in the mining towns of the area. In her 30's Susan contracted tubuculosis and came to the Fraser Valley in hopes of a cure in the clear mountain air. Not only did she regain her health, but she he practiced medicine from 1909 to 1956 in Grand County, a total of forty-seven years. People in the area were very poor and seldom paid in cash. They usually gave her meals for payment. This suited her fine because she did not like to cook or keep house, which was always messy. Because the railroad ran beside her shack, she often would be called to various parts of the county, even at night. Doc. Susie would flag down a train and ride wher ever she needed to go, free of charge. She also treated the men working on the railroad and their families in Fraser and Tabernash, which was about three miles northwest of Fraser. Around 1926 Susan became the Coroner for Grand County. One time she hiked eight miles on snowshoes to a ranch because she was con cerned about a woman who was due to deliver her baby soon. That night the mother gave birth to a baby girl. While there, the four-year-old son had an appendicitis at- tack. Neither of the parents could take the boy to Denver for surgery. Doc Susie took him by train. A blizzard hit, blocking Corona Pass. The men passengers were called out to help clear the track It wasn't until the next morning the train arrived in Denver Doc Susie had no money for a taxi fare. The passengers gave her the taxi fare to get from the depot to Colorado General Hospital. Doc Susie stayed with the boy during the surgery from which he fully recovered. Another time Doc Susie rented a horse drawn sleigh to go as far as she could, then snow shoed into a ranch in a storm to treat a child with pneumonia. She had the rancher heat his home as warm as he could, heat water and then put the child in a tub of steaming hot water and open the door to make more steam. By morning the child had recovered. SDoc Susie lived to be ninety years old. The last two years of her life she was cared for in a rest home by the doctors for the Colorado General Hospital out of respect and love. Susie wanted to be buried beside her brother in Cripple Creek, but because of bad record keeping, no one could find his grave until later. She was buried in a new section of the cemetery. When the residents of Grand County learned there was no head stone, they took up a collection and erected a headstone. Susan Anderson never married, but she said she had delivered more children than any one and claimed them as her children. Her family was everyone in Grand County. Her home still stands in Fraser and the Cozens Ranch Museum has a display of her life and medical tools.

|

| Dr. Sudan |

Dr. Sudan

Article contributed by Barbara Mitchell The people of Grand County have been lucky to have good doctors from early times to the present. Such a one was Dr. Sudan.

|

| Ed Vucich |

Ed Vucich

Article contributed by Jean Miller Ed stood, ramrod straight, in front of his tiny green house, checking out the day: sky clear blue; clouds soft and fluffy; wind just a light breeze that gently lifted his thin white hair; Brown’s cow feeding in Millers’ yard, as usual; Old Lady “Ada” (aka, Mrs. Zeida) getting ready to water her Oriental poppies. The day was on its way. “Ha! Here comes Dwight to chase off that darned cow. He goes through this every day. I bet one of these days he’ll have fresh cow meat for supper!” Ed returned inside his cabin, to feed the stove and make coffee. The fact was he didn’t need any more heat. He kept the place about 85 degrees, summer and winter. But Ed was so thin, cold went through his worn body easily. Soon he poured himself some coffee and went out to talk to Mrs. “Ada”. “Hello there, old woman. Those poppies are the prettiest you you’ve had for years. You should win a prize.” “Thanks, Ed. I agree that they’re especially nice this summer. Brown’s cow has left them alone for a change.” With a laugh, she went back in her house. Dwight Miller wandered over to chat. “Mornin’, Ed. How’re things?” “Well, just fine, except you’ve got to tell your cabin guests to quite using my outhouse! I saw three of them coming out of there early this morning. Tell them to use their own! I’m going to build me a fence.” Dwight looked apologetic. “Boy, Ed, I’m so sorry. You know, sometimes they just can’t wait, so they invade ours. But I tell you what, I’m going to put in a regular bathroom at the back of my garage, facing the cabins. I hope, at least, that will take care of the problem. In fact, if you want, I’ll give you a hand on your fence. I don’t blame you for being irritated!” Ed was mollified with this offer. He had lived in his cabin for some years now, after finishing up his days as a tunnel worker in 1927. He used to tell Dwight, “Back then, there were prostitutes behind every tree up near the tunnel, and if you paid them a quarter, they’d give you 15 cents change!” He was Austrian and had served many years in the Austrian army, but he got fed up with all that and came to Colorado to live. The mountains reminded him of his home country, and his life style remained just as spare and regimented as it had been in the army. Everything was neat as a pin. The old man kept track of his neighbors’ comings and goings, including Dwight’s wife, Jean, and their toddler, Martha. He used to really fuss at Jean, because she insisted on whistling. “Jean, ladies don’t whistle!” But Jean liked to whistle, so she continued not being a lady. The baby was another subject. Dwight had built a ladder coming down from their apartment on the upper floor, as a second exit in case of fire. Martha learned to climb down that ladder before she was three years old. “Dwight,” Ed would protest, “that baby is going to kill herself! She¹s going to fall; then where will you be?” But Martha seemed to do just fine with her climbing and she never did kill herself! One day Dwight bought a small Army surplus life raft. Opening it, he discovered some dye, to be dumped into the ocean so that planes could spot men in the water. “Hm-m,” he thought, “I wonder if this dye really works?” So he went up to the bridge over Vasquez Creek and poured some dye into the water. Yes, indeed, it worked. The bright red color spread into a great circle in the creek and promptly flowed downstream. Dwight hightailed it down to his house, to see if the color still held. Here it came, and here came Ed Vucich, madder than a hornet. He had spotted the dye and was quite positive that Dwight was trying to poison him and all the others who used the creek water for drinking. In spite for fretting and stewing over illegal outhouse use, “poisoned” water, babies on ladders, and unladylike whistling, Ed cared for the young couple. On day as Dwight and Jean were about to head into Denver, he came rushing out and stopped them. “Here, I have something for you!” And he presented two beautifully baked potatoes, straight out of his oven. They were perfectly lovely. Ed swore up and down that he didn’t drink, but in fact, he was known to visit Wally’s Bar on the highway into town. One bitterly cold night, Dwight and Jean heard a rumpus going on outside. In those days, winter temperatures dropped regularly to minus 40 to minus 50 degrees. Getting out of bed, the pair went to look out their front window. Ed was attempting to get into his house, which he kept locked with three different padlocks (why was a mystery; he had very few belongings). Perhaps he wasn’t drinking, but he certainly wasn’t sober. He tried to open a lock; his feet slid out from under him and he swore, “Damn!” He struggled back onto his feet again. Same result. The young people didn’t dare just leave him, hoping he would finally get into his house he’d have frozen to death. But if they had interfered, oh, he would have been furious. So they watched until at last all three padlocks were open and the old man staggered inside. They never told him about the show he put on! Ed lived in Hideaway Park for a number of years longer, but it’s uncertain as to where he is buried. Dwight is convinced there probably aren’t as many characters in the valley as there were fifty some years ago.

|

| Fire Engine No 1 - Hideaway Park Fire Department |

Fire Engine No 1 - Hideaway Park Fire Department

"What Hideaway Park needs is a fire engine! No way can we fight fires without more water; all we can do is watch some building burn!" The half dozen volunteer firefighters were seated around the table in Hildebrand's little grocery store on Highway 40. "I agree," said Ray. "We've talked long enough! Who's got the want ads?" Claude pulled out the latest Denver Post want ads. "I don't see any fire engines. I looked up fire fighting equipment too. Nothing there. But here's a 1940 Chevy truck for $400.00. That's just eight years old; maybe it would do." "We could mount a tank and a pump on the back," said Dwight. "Do we have enough money to pay for it?" Claude pulled out their account book. " We've $550.00. That would pay for the truck and we volunteers could use the rest to put up a shed. We can always have more Bingo nights. "Dwight, you're the Fire Chief. Why don't you and Ray go down and look at it. We'll give you a blank check so you can bring it home if it looks good." The men agreed. At last they were getting started. The following week Dwight and Ray drove to Denver to the car lot and took a look. The truck wasn't much, but the engine worked and the tires weren't too bad. Ray commented, "I know a fellow who has a galvanized tank. We can buy some 2" hose and a pump from American LaFrance. "Okay," said Dwight. "Let's take it." He brought out the check Claude had sent along and signed it. The used truck salesman looked at it and looked at Dwight. "How old are you, Mr. Miller?" "I'm 20 years old," he answered. "What's the problem? I'm Fire Chief." "Hmph, you look more like sixteen! We're not supposed to take checks from anybody younger than 21. Let me go talk to the bookkeeper." It took a long time and Dwight and Ray were getting nervous. At last the salesman returned. They'd accept the check. And so Hideaway Park got its very first fire truck. The men in town finally got the tank and pump put together and started in on a wooden building, along the main road off Highway 40 where Cooper Creek is now. Winter came early that year, and the fellows didn't have time to get the roof completed. The rafters and sheeting were up, but the 90# roofing material had to wait; so snow drifted in with every storm, and ice built up, to melt and leak later onto the truck. But the men knew they could finish up the following year. Periodically they got together to try out the pump and drive up and down through town, with their new siren wailing. Everything seemed to work. A few years passed. When fires occurred, however, the buildings still usually burned to the ground. One winter in 1952, Dwight was wakened before midnight. "The Spot is burning. Let's go! Let's go!" Ray's voice broke with excitement. Dwight jumped from bed and threw on his clothes. He could see the flames down on the highway leaping above the trees. Men were gathering at the firehouse. Dwight ran through the door and clambered up on the fire truck. He tried to start the engine. R-r-r-r --. Nothing happened. R-r-r-r. "The battery is dead," he cried. Ray and Wally were struggling to get the overhead door open and the miserable thing was frozen shut! They took a hammer to the base, but the frost wasn't about to give way and let door move. Finally Dwight cried, "Let's slip a cable under the door and hook it to the truck. We can pull the truck out and on down to Vasquez, to fill the tank." The cable was soon in place and Claude jumped into his truck and started pulling. With the fire truck in gear, it moved forward, hit the double garage door, and continued on. With a groan and a jerk, the engine and siren finally started. Dwight guided the rig onto the road with the door riding on top of it, blinding him. At last, the door fell to the ground. At the creek, the fellows pulled the hose down to the water and chopped a hole in the ice. Another started to hook the hose onto the pump. "The hose has shrunk! It won't fit!" "What? It did the last time we practiced!" The volunteers looked at each other and threw up their hands in disgust. The Spot to Stop was burning fiercely by this time, but Ray said, "Let me string my garden hose across the highway. I think it's long enough, and maybe it will do some good." This is what he did, but it was too late. That building was a goner. The townspeople stood around until there was nothing left but ashes; then they went home to bed. The firemen met the next morning to decide what to do about the truck. They eventually chose just to leave it there all winter. It sure wasn't going to do anybody any good. The next winter, that fire truck had a new hose! Some years later, Dwight and Jean Miller gave land for a volunteer fire building, which was made of metal and which had a heater. And over the years, better trucks were purchased and the men received some proper training. The early volunteers had a perfect record ? they never saved a building. Some of the volunteers in 1947-48; there may be others. |

- ‹ previous

- 2 of 7

- next ›

,

,  ,

,