Community Life

What was it like to live in Grand County in the 1800's or the early 1900's? .

Community Life Articles

| 2006-100 Year is Here |

2006-100 Year is Here

Poem, contributed by Vera Shay, August 2006 Since the railroad tracks Were all laid down Trains coming into Kremmling town Only books, left to tell and say Of the excitement that day Of the thirties and the forties It is so Of the railroad tracks and trains I do know I rode on them everywhere Here and there During those years in my mind I owned them all you see That I would have told you Had you asked me. Todays trains all have a brand new look Inside and out Riding on the trains from them till now There is no doubt The train crew and passengers of today Still just as fun and great Though they seem to always be running late Lots of folks think they're just too slow For me they've always been A wonderful way to go Trains, trains Let there always be trains

|

| 4th of July Parades in Granby |

4th of July Parades in Granby

, ,  , ,

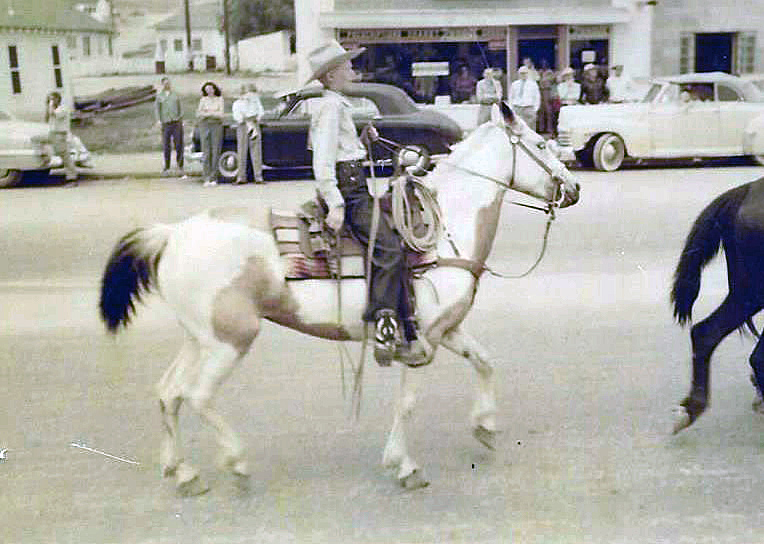

In 1947 my family moved to Granby, Colorado; I was 5 years old. My Mom (Eloise) and Dad (Howard, “RED”) Beakey, ran the Texaco gas station where the Chamber of Commerce parking lot now sits. I have a sister named Sandra Sue, who was 3 at the time. In 1948 Mom and Dad bought me a mare named Midge, and that is the beginning of my joy of growing up in Granby. I rode Midge all over Granby and surrounding area. In the winter I would pull kids on their sleds and skis with a rope tied to the saddle horn. In the spring of 1949 Midge produced a filly foal that we named “Lady Blaze.” The following 4th of July Rodeo Parade, 1949, I rode on Midge and my friend, Howard Ferguson, rode behind me and led Lady Blaze in the parade. A local farrier had made lace up booties with metal bottoms for Lady Blaze so she wouldn’t damage her hooves while being led in the parade. You can imagine the sound of those booties hitting the pavement as we rode down Agate Ave., and the enjoyment of the crowd lining the parade route. At that time the rodeo grounds were in the area of N Ranch Road. The Granby Fire Department awarded me with a $3.00 check for being “The Most Typical Cowboy Under 12.” I was totally amazed and still, at the age of 79, have that check! I did give Howard $1.50 in cash, though, that day for his part. The following year, 1950, Mom and Dad bought a Pinto filly from Tex Hill, the Foreman of the Little HO Ranch east of Granby. Tex rode the Pinto into the gas station office one day and asked my Dad if she was gentle enough for me. Dad said yes, and I became the proud owner of my second horse, which I named Melody. That year (1950) my sister, Sandra, rode Midge and my Dad rode his hunting horse, Spike, and I rode Melody in the Rodeo Parade. Prior to the rodeo Dad (who hadn’t ridden Spike in a long time) got bucked off into a pile of rocks and got pretty banged up. Sis rode up and asked Dad (who was laying on the rocks) “are you dead Daddy”? Sis and I rode all over Grand County, riding along US 40 to 10 Mile Creek to fish the beaver ponds; we would be stopped several times to have our photos taken by the tourists. Tourists always seemed amazed to see little kids riding on horseback way out in the country. We always brought home from our outings some nice Brookie trout. Sometimes we would ride out to The Little HO Ranch and spend a few days there with playing real live cowboys with Tex, while Sis would help his wife around the house. In 1951 Tex Hill brought a full sister to Melody, named Patches, for Sis to ride in the parade, so, we rode side by side. That same year Eddie Linke Jr. asked me to ride his racehorse in the rodeo race. We went to the rodeo grounds several days for me to get used to the horse. Of course, the horse was not as gentle as Melody, so I fell off several times before getting use to him. The best part is that I did win the race, and was happy and proud riding Eddie’s horse. In 1952 I once again rode Melody in the Rodeo Parade, which was sad for me as it was the last one, I attended before we moved away from Granby to Arvada. Mom and Dad sold both the horses. I guarantee several tears flowed because of that. One of the other great things I enjoyed was going to a cow camp in the summer. A friend of my parents, Rocky Garber took me to cow camp that was behind Trails End Ranch on Willow Creek Pass. We packed our supplies in on pack horses to a small log cabin. I was so excited to be a cowboy, moving cattle from one grazing spot to another, even getting covered with mud pulling a heifer out of a mud bog. The second time I went to cow camp was with my Dad’s cousin Louis “Newt” Culver, who in my mind was the greatest cowboy ever. The cow camp was below “Devils Thumb” east of Tabernash. It was a log cabin next to a creek and had corrals to keep horses. Once again, I loved the excitement of being a cowboy. We would go to the high meadows checking on the cattle and occasionally have to chase an ornery bull back to the herd. In the evenings Newt would train horses to be good cow ponies. When they were gentle enough, he would let me ride one while he rode another that he was training. So, some of my greatest memories of my life are the years I spent in Granby and Grand County, not a better place for a kid to grow up! I graduated from Salida High School in 1961 and our family moved back to Granby. Mom and Dad had the Texaco Station in Fraser. I joined the Air Force in 1962 and retired after serving 26 Years. By Joe Beakey - Poncha Springs April 2022 |

| A Broadcast Pioneer of Colorado |

A Broadcast Pioneer of Colorado

Article contributed by Jean Miller How times have changed! Today every TV station has a least two weathermen and every newscast has innumerable weather reports, usually given as fast as the tongues will move and repeating the same information ad infinitum. There was a time when this wasn't so. Back in 1950, TV stations were still unknown in Denver. KOA was probably the most influential of the radio stations. (KLZ was established two and a half years before KOA in 1922.) On New Year's Day, 1950, a slender young man arrived in town from Des Moines, Iowa: his name was Ed Bowman. Ed was born and raised on a farm in Iowa City. He loved weather and he loved to fly. Ed was convinced that in order to talk about weather, one should understand the sky, and flying was the way to do this. Ed had cut his broadcasting teeth with WHO in Des Moines (at the same time that Ronald Reagan was the station's sports announcer). In December 1950, Bowman managed to secure a reporting job in the newsroom for KOA Radio. On Columbus Day, 1952, KBTV (Channel 9) started to broadcast. The following June, KOA Radio was sold by NBC to Metropolitan Television Company, one of the principal stockholders being Bob Hope. That Christmas Eve, KOA radio became KOA-TV, or Channel 4, and for the next thirty years, those were the call letters of this station. Ed Bowman was picked from the radio newsroom to be the weatherman, supposedly because his name rhymed with weatherman. (A bit of a stretch.) For the following twelve years, he was the only full time weatherman in the Rocky Mountain Region. Ed quickly became "Weatherman Bowman" and his distinctive mid-western drawl was well-known to Denver listeners, who turned to his report every day at 5:05 p.m. Ed was also heard in the mornings, flanked by ads for Cream of Wheat. (It's Cream of Wheat weather: let me repeat. Guard you family with hot Cream of Wheat.) Weather reports had no quick-moving computer graphics in those days; no mountain-cams, Denver-cams, highway-cams, or ski-area-cams. Fortunately, Ed was a skilled artist, who, every night, created weather maps right in front of our very eyes. His maps were filled with wonderful clouds and arrows showing wind directions; his "troughs-aloft" guided the listener if figuring out the next day's activity. This was the first time the term "trough aloft" was used to define weather. These hand-drawn maps have become collectors' items. Ed and his wife Madelyn lived with their family in Littleton. He flew his Fairchild trainer airplane every chance he got. One of his treasured possessions was a Norden bomb sight, a highly secret device used during the war, which he was able to purchase from the Air Force afterwards. During this time, before the Air Force Academy was completed, cadets were housed and trained at Lowry Field in Denver. One day, Ed lent two of the cadets his plane, to take for a flight "around the patch" south of the city. Something went wrong during the flight; the Fairchild crashed, and both men were killed. Ed never really got over the loss of these young men. Ed was a congenial fellow, and his no-nonsense approach to weather reporting made him the person to whom everyone turned each day. Emphasizing his background as a pilot and looking more dapper than ever, he sometimes donned goggles and a white scarf, as he gave his report. Bowman occasionally broadcast from his home studio, particularly during severe storms, when driving to the studio in downtown Denver was treacherous. He related how once, when he overslept, there was no time to research the weather. So he hurried to the door, looked outside and found it was raining. He told his listeners that there was a 100% chance of rain and he held his microphone to the door so that they could hear it pouring down! "Just listen to that!" he said. We became acquainted with Weatherman Bowman in the late fifties, because he loved to come to the mountains to stay at Ski Idlewild. Old Dick Mulligan was a colorful fixture at Winter Park Ski Area in the early days, and his wife was a Weatherman Bowman fan. She wanted to meet him in the worst way; so once Dwight took Ed over to the Mulligan's house for a chat. This really made her day! Dwight also lunched wi h Ed frequently when he was in Denver. For six months or so, we sponsored the weather report, which, though expensive, was great fun. Weatherman Bowman left Channel 4 TV in 1965, perhaps not entirely willingly. His fans felt that nobody else ever matched his skill. Ed continued reporting for some time, however, broadcasting for a Kansas radio network from his home studio. Ed Bowman died on July 4, 1994, and he was inducted into the Broadcast Pioneer Hall of Fame in 2001. The Hall of Fame, established by the Broadcast Professionals of Colorado in 1997, is dedicated to preserving Colorado's rich broadcasting heritage, and honoring those who had made significant contributions to this field.

Additional memories of Ed Bowman from reader Glenn Wolfe "Ed Bowman was a favorite of mine. I can't resist a few stories based on the year I worked in the newsroom with him. After the 10-o'clock TV news every night people would come to the lobby of our building because he would give away the hand drawn pastel weather map he had created for the broadcast -- signed, of course. The engineers and camera operators loved the guy. On one occasion we had a surprise, late spring snow storm. During his live TV weather cast the studio crew lobbed snowballs at him. He was so serious about providing accurate, usable weather and forecasting information that he spent some vacation days in eastern Colorado and Nebraska (part of our radio coverage area) talking to farmers and observing the wheat harvest. He wanted to know that they needed to know about the weather. The news room at KOA was a cement block structure with no windows. Ed's desk was right in the middle, connected to various weather instruments on the roof, including a rain gauge. The gauge consisted of a collection funnel on the roof. The water ran down a tube, through the ceiling, to a calibrated beaker right on his desk. Well, it had been an absolutely clear, dry day....not a cloud in the sky. Just as Ed was preparing his broadcast, one of the cheeky engineers peed into that funnel! What a nice man he was, even to this total green horn just out of college."

|

| A Good Man |

A Good Man

A Good Man contributed by Richard Shipman All of us have those wonderful people in our lives who quietly go about their daily activities without complaint. They don't stir up the wind or people's lives with grandiose actions. And at the same time, many of them have a great impact on us. Thankfully, I know one of those people. He is a son of I first met Fred Wood in 1967 when my brother married the eldest daughter of Fred and Mary Wood. It has been fascinating and rewarding to get to know Fred, his immediate family and extended family. The first thing I learned about Fred was his kindness and love of family. Almost immediately I was included in all family activities: the birthdays, anniversaries, and trips back to the family cabin near Williams Fork Reservoir. I was about the same age as his oldest sons and I suppose it was just easy for him to look at me as one of his boys. I was always extended a warm and sincere invitation to come to the annual summer and winter mountain events. We all had great fun, all fifteen to thirty of us. These events frequently pulled in the families of Fred's older brothers who worked the family ranches in the Williams Fork area. Loyalty and dependability are important to Fred. At the end of this year he will complete his 60th year working for the same employer. That is quite an accomplishment these days. He is always there training the new people and sharing his knowledge and work ethic. It says a lot about one's character to stick with something for that many years. Probably the most important accomplishments are the 59 years he has been married to his lovely wife, Mary, and raising their 10 children. Fred works for a moving company. This job requires a great deal of physical strength, much of which he gained working on the family ranch near Parshall, where he was born. I've witnessed his ability to do hard work when we cut trees for firewood, added to the cabin, or dug out the basement. Fred was born in 1924, the youngest of 13 children. Growing up in the 30's gave him a good understanding of the value of hard work and the determination to find a job to support a family. Like most of the people of his generation, the love of family and country put him on a path to service in World War II. It's only been in the last few years that I have learned about Fred's service and how much our country asked of those young people. Fred and his peers have shared some stories and now national authors have recognized the "greatest generation." You see, most of these people are modest and humble folks who were just asked to do a job and they went out and did it with no expectation of special recognition. Fred was a crewmember on a B-24 Liberator bomber flying out of I recently had the opportunity to fly in a renovated Liberator and I am amazed at what little the pilots had for protection. And that they were asked to do so much with so little. Another thing that you learn from these people is humility. The world that they saved us from was so brutal that they have kept it all to themselves for more than forty years. Now as time draws to a close on their times, the remaining crewmembers relish their annual get-togethers. They are always invited to share the cabin. For most of Fred's adult years he worked in You can see where I am going. Here is a man who lived and worked through the country's most trying and challenging times. I can see his strength of character, dependability and devotion to family and friends. Make no mistake; he did not make this journey alone. Mary has been a partner from the first. They have shared the triumphs and tragedies together. And they continue to lead their family. It has been an honor for me to be part of this remarkable family lead by an unassuming, gentle man. I feel privileged to know this good man and to have him as a friend.

|

| A Man Called Blue |

A Man Called Blue

“Blue” should have been a grouch, with a name like that. Nobody who knew him seems to know why he was called this; his real name was Rudolph O. Cogdell. If one went into his little grocery store in Fraser, although his voice was gruff, he gave a peasant greeting. He did possess a temper that could be ignited, and if his blood pressure rose, his face turned a brilliant red. |

| A Story from Big Horn Park |

A Story from Big Horn Park

And Then There Was Light They were perched on the side of the road in Big Horn Park peering out the window at twilight as their eyes moved across the Troublesome Valley below and then up to the high mountains of the Gore Range. From this distance it was obvious why early settlers, having trouble forging the creek, had appropriately chosen that name for the valley. Paul pointed out the window to the right and said, "That is where my great-grandparents lived." His ancestors had first homesteaded in Wray, Colorado before moving to Grand County around the year nineteen hundred and eighteen to ranch up on the Gore Range. They headed down the gravel road to the ten acres of land just purchased not far from his grandparent's property. "Legend has it," Paul continued, "that on a bright, summer morning, Henry rode up to the timberline above his cabin to cut down the last load of trees needed to build a barn. "Clara, his wife, called after him, ?I will bring your lunch when the sun is high in the sky.' "Early in the morning", Paul explained, "she cleaned the tiny cabin and prepared food by the light of a kerosene lamp. When the sun was almost straight above the cabin, she dressed and left by horseback with lunch for her husband. When Clara reached the top of the ridge, she could see Henry preparing to fell the last tree. Excitedly she headed up a final hill and dismounted with the lunch in her right hand. Climbing quickly, Clara called to Henry distracting him from his chore. "Then suddenly from high atop the ridge above him," Paul added, "Henry heard the terrifying cry of a lone, grey wolf. The scream was shrill to his ears, and his heart stopped beating for a moment before he looked around to see that the tree had crashed instantly to the ground. All was silent on the mountain as he descended to find Clara dead beneath the branches of the tree with the lunch still in her right hand. It had happened so quickly that Henry never heard one sound escape from Clara's mouth. And even today as the morning sunlight outlines the evergreen trees on Elk Mountain, you can see the silhouette of a woman's face with her hair flying wild and free in the wind and her mouth open wide, crying out for help. "They called him O'Grey", he added, "but they never saw or heard from that wolf again." Life in Big Horn Park in the nineteen-eighties when they bought the land was still challenging; no electricity or running water was available to provide creature comforts to local inhabitants. Over the years, while a house was being built, they washed in a small stream of water that trickled down across the property from Monument Creek. Neighbors used kerosene lanterns to illuminate the night and gasoline generators to pump water from wells. Bears often tried to enter basements for food, and mountain lions crawled onto decks to devour small dogs or cats. Only one or two hardy families lived in Big Horn Park in those days through the long winters. Skis provided a way of escape in the event of a winter blizzard that often dumped snow deep enough to cover the tops of the three-wire fences. And then there was light. Paul flicked on a switch in the house and radiance encircled them, startling the cats and engulfing the room. That marked the beginning and the end of time; old ways faded and new, exciting possibilities emerged. It was almost Christmas of the year two thousand and two, and the first holiday up in Big Horn Park was beckoning. If not for the electric heat installed during the summer, the trip would have had to be postponed for another year. Only by chance can the mournful howl of a lone, grey wolf be heard today, but the cat cries of the fox emerging from a den can still awaken a soul at midnight in the summer or the yipping coyotes can be heard as they call to one another in the silent, winter night. And the tracks of a lonely, mountain lion lopping across the hillside beside the cabin can occasionally be found in the snow. The experience quickens the heart and revives the spirit as the Jeep is loaded with suitcases and cats, and a turkey with all the trimmings. From Utah across the high, barren desert and up the winding Trough Road the old Jeep transports the family to fulfill the dreams of a lifetime. A slender sled is removed from the Jeep as the attached silver bells jingle. Supporting their bodies against the door, the man and woman grab their snowshoes to slip them on and tie the leather straps securely. Cats and turkey dinner are hauled through the pristine snow like times of old to the garage door. A blast of bitter cold air escapes from the house when the door is opened, chilling the bones, but the electric heat will melt away the cold air while they climb the low hill to inspect tracks left in the snow by tiny creatures. Soon flickering lights from a fresh, Christmas tree on the second floor loft cast playful shadows across the living room below. In a small room above, two single beds snuggled against the outer walls are spread with warm comforters. All manner of toys, games, and bright objects decorate the room, awaiting a grandson's arrival. For the adults, the smell of the turkey and the taste of pumpkin pie revive childhood dreams of holiday celebrations of long ago. Laughter and pleasure emerges from the snug cabin and records are played on the old turntable chanting, "Silver bells, silver bells, soon it will be Christmas day". Thus begins a new life for them; not only can the family survive "up on the Troublesome" again like their ancestors from the shadowy past, but a livelihood can be earned. As summer arrives a light will flash, a screen will brighten, and online learning will occur as distance education courses will be provided to students in Maine and other states from a small cabin located over eight thousand feet above sea level in a remote, northern corner of Colorado. |

| A Walk's Excitement - Anniversary of September 1945 |

A Walk's Excitement - Anniversary of September 1945

Contributed by Vera "Stathos" Shay, Kremmling Granby resident 1930-1945 I walk, walk here there and everywhere; I walk alone down the hill I see our beautiful red, white and blue High on poles waving, waving proudly over town. No, what is this! Daddy's with me. He said to me wait, wait I'm going with you. This must be important. Daddy never joins crowds and there is a big crowd. It seems the whole town is gathering. Everyone is so happy and excited Some people are waving American flags. There is music, cheering, singing and dancing. Daddy has brought along with us one of his track railroad flares. He is lighting it. He before has only lit one of them for our family to celebrate on Fourth of July. What is going on? Now everything is quiet. Then someone is shouting. Japan has surrendered. Japan has surrendered. Now I know. Hurray! Hurry! The war is over.

|

| Arapahoe Ski Lodge |

Arapahoe Ski Lodge

Article contributed by Chris Tracy, Courtesy of Alpenglow Magazine 2009 The Arapahoe Lodge's history has everything to do with a perfect ski vacation experience. 2009 celebrates the lodge's 35th anniversary. Rich and Mil Holzwarth and their children (now adults) Jan and husband, Greg Roman, Brad and Todd have lovingly operated the Arapahoe Ski Lodge since 1974. That was before there were sidewalks and street lights- when the town was still named Hideaway Park. It was before Mary Jane, and snowboards, when a day of skiing at Winter Park Ski Area was $7.50; when old Ski Idlewild boasted a $6 lift ticket; and lessons at both resorts cost a whopping $8. It was before snowmaking equipment allowed the resort to open early, and when phone calls still went through a friendly local switchboard operator, and calling Granby from Winter Park was long distance. "Our number at the lodge then was Winter Park 8222," Jan recalls. Other ski lodges in operation included Idlewild Lodge, Timberhouse, Beaver Lodge, High Country Inn, Woodspur, High Forest Inn, Yodel Inn, Sitzmark, Miller's Idlewild Inn, Brookside, Winter Haven Lodge, Tally Ho, Outpost Inn, and Devil's Thumb. Like the Arapahoe, most had a bar, sauna and hot tub. Now, only a few of the grand old lodges remain. Condos and hotels have taken their place, and guests who frequent them unknowingly sacrifice a romantic, unique experience only a ski lodge can offer.

|

| Barney & Margaret McLean |

Barney & Margaret McLean

It was the spring of 1924 when an 8-year-old girl from Hot Springs, Ark., arrived in Hot Sulphur Springs by train to spend the summer with her aunt and uncle Hattie and Omar Qualls, homesteaders from Parshall who had recently purchased the Riverside Hotel. It wasn't the first time Margaret Wilson had been to Hot Sulphur. Her father had tuberculosis and was frequently prescribed treatment at the sanatorium on the Front Range. She was 6 years old the first time she made the train trip.

Hot Sulphur had four ski hills back then and Margaret recalls that in February 1936 the Rocky Mountain News sponsored an excursion train to the 25th Annual Winter Carnival in Hot Sulphur. More than 2,000 passengers arrived on three trains that weekend. (That same train later became the official ski train. |

| Brrrr! |

Brrrr!

Article contributed by Jean Miller So many people ask if it is true that winters used to be much colder up here. The answer is yes. We could generally figure on one to two weeks of nights between minus 30 degrees to minus 50. This usually occurred between the middle of November and the third week of January. (Please note that we also didn¹t have pine beetle infestations during those years.) We Fraser Valley folk depended on weather reports kept by Ronald and Edna Tucker, who for many years faithfully read thermometers day and night. It was through their efforts that Fraser came to be known as the “Icebox of the Nation”. These were the years when it was guaranteed that the power would go out, usually on the coldest nights when you had a crowd in the house, for the REA had not existed very long and they suffered from many glitches and equipment failures. Occasionally somebody would set his house afire, trying to thaw pipes entering from the outside. The incident I am going to relate was in mid-November 1951, and I had just delivered Dwight to the airport, to leave for his required two weeks Naval Reserve active duty in San Diego. I took advantage of the break to stay with my family in Denver for the night. I was an innocent city girl, and at that time I didn’t realize the connection between being overcast for a week (which we had been) and what happens when the sky clears (which it did). I got home to Hideaway Park in the late afternoon, just after dark. It was so cold! I checked the house and put more coal in the stoker. All was in order. Next I went over to the Inn (Millers Idlewild). As I opened the front door, I heard water running, as in a waterfall. The noise came from the kitchen. When I went to check, I saw a spray of water shooting from the sink all the way across the room, drenching the stove. The floor was an ice skating rink. I couldn’t believe my eyes. As far as I could tell, it was as cold inside as out. I tried to shut off the water at the sink, but the pipe was split. I ran to the laundry room and searched for valves, but everything I tried did nothing at all. At last I drove back to the highway to Ray Hildebrand’s house. He and his wife Mabel had a small grocery store and Hideaway Park’s first post office. Ray, one of the few people I knew in town, kindly came to my rescue. He found the main valve hiding behind other pipes, and the geyser in the kitchen fell silent. Then I built a fire in the furnace. Now I was a poor ignorant city girl. For years my family had had natural gas; when it got cold, we turned up the thermostat. What did I know about stokers, sheared pins, and augers, tuyeres and clinkers? A lot of nothing. That was a rough two weeks. The night temperature was never warmer than 35 below. I mopped up the mess in the kitchen, once the place warmed up a bit and the water thawed, but I just left the split pipe situation for Dwight to deal with. I struggled the whole time to keep the Inn above freezing. I was afraid that if I gave up, every pipe in the place would burst and I was embarrassed to call on Ray Hildebrand again. Dwight’s weeks were finally over and I picked him up once more. I was so glad to see him! Indeed, I hoped he wouldn’t leave again for a very long time. He was a dear boy and I did miss him. Besides, he knew all about pipes and pumps and furnaces.

|

- 1 of 7

- next ›

,

,