People Articles

| Tabernash |

Tabernash

The unrest and hard feelings between the Indians and settlers in Middle Park gave rise to an inevitable conflict the last week of August, 1878. About forty Utes, led by Piah and Washington, started to set up camp in William Cozens’ meadow, near Fraser, taking fence poles to make fires. Cozens drove them off, telling them to replace the poles and leave. The Utes moved down valley about five miles to a spring not far from Junction Ranch (named for the junction of the Rollins Pass and Berthoud Pass wagon roads). There, Johnson Turner, who leased that land, became increasingly uneasy as the Indians were drinking heavily and expressing anger that Ouray given away their land in treaties with the white man. They wanted Turner to pay them for the hay he was cutting. They tore down his fences for firewood, turned their 100 horses into his meadow, and set up camp. They also laid out a race track on drier ground about a mile way. Turner complained to the sheriff, Eugene Marker, who rounded up a posse of men, intending to remove the Indians or at least convince them to move on. Accompanying him, on September 1, were Frank Addison, a transient prospector, John Stokes, T.D. Livingston, and Frank Byers. The posse found only women and children at the camp, since the Ute men were at the race course. Marker, the sheriff, ordered the encampment searched for firearms and when the Ute men returned, an angry confrontation ensued. Tabernash and Frank Addison exchanged threats, and Tabernash jumped from his horse and snatched one of the guns piled on the ground. Frank Addison immediately shot him. Tabernash tried to pull his rifle from its scabbard, but that it became entangled, and Addison then fired twice more. Tabernash slumped over the neck of his pony, which ran away through the willows. Apparently Addison recognized Tabernash as the Indian responsible for the killing several of his companions while trapping furs on Grizzly Fork in North Park six years earlier. |

| The Daily Life of Mountain Men |

The Daily Life of Mountain Men

Washington Irving wrote "There is, perhaps, no class of men on the face of the Earth who lead a life of more continued exertion, peril and excitement, and who are more enamored of their occupations, than the free trappers of the West". The diet of the mountain men at times consisted of nothing more than meat. When possible. wild plants and berries supplemented needed vitamins. Pemmican, a meat pounded with fruits and dried in flakes, was convenient to carry and lasted a long time. Mountain men made boudins, sausage made from the intestines of newly killed animals. These sausages were packed full of undigested grasses which probably protected the mountain men from the illness of scurvy. The mountain men also chewed on leaves and wild grasses to supplement their vitamin needs. Potatoes soaked in vinegar supplied further balance to the diet. Jams and orange marmalade were highly valued whenever they could be obtained. Bread consisted almost entirely of hardtack, a touch cracker usually unsalted, which would not spoil and sturdy enough not to crumble. Beaver tail soup was considered a delicacy by most mountain men. Another treat was called "French dumplings", made by mincing buffalo hump with marrow, rolling it into balls, and covering with flour dough and boiled. Coffee was popular, but limited for transport. Tea from China came in solid blocks which could be shaved off as needed. Normally, mountain men could not carry whiskey on the move but at rendezvous or during visits to forts, they were known as fabulous drinkers. The most common intoxicant in those days was "Taos Lightening", a strong whiskey manufactured by Simeon Truly of Taos New Mexico. Various writers have portrayed these men as brutes who lived from one drunken episode to the next, but the facts, and common sense contradict that image. They could not achieve much in either trapping or trading if they did not stay focused on their outdoor skills and survival. Smoking pipes was a luxury, mostly at nights as only a limited amount of tobacco could be obtained. The mountain men would stretch their tobacco supplies by mixing it with kinnick-kinnick and other plants. While many traders and trappers dressed in buckskin shirts and trousers, wool garments were even more common and needed to be shrunk to fit. Probably every mountain man carried what was called a "possibilities bag" that contained personal items such as a pipe, tobacco, soap, needles, and small keepsakes such as mouth-harps. Before the Sharps "Big 50" rifle was invented, it was necessary to carry a waterproof powder horn and a bag of rifle balls weighing fifty to a pound. A good knife was essential. The most sought after of these was the Bowie Knife, invented by Rezin Bowie, but made famous by his brother Jim, who was adept at its use. Jim was one of the heros killed at the Battle of the Alamo in Texas. Some mountain men simply loved the lifestyle and had no reason to return to their original homes. Some had wives back in St. Louis and made an annual trek there every year. Others had Indian wives or female companions. Some men claimed to have a wife in every tribe they visited. Divorce within many tribes was often simple, a matter of putting one's belongings outside the lodge. As journeys by foot or horse were lonely, mountain men were known to play their mouth harps or sing songs along the trail. The use of profanity was common, except in the presence of white ladies. One writer claimed the Indians called white men "Godams" because that swear word was used so frequently by the mountain men, ranch hands and mule skinners. |

| The Ish Family |

The Ish Family

The prosperous John Lapsley (Laps) Ish family are an example of very successful settlers and entrepreneurs in early Grand County. The Ish family, with eleven children, came by covered wagon to Colorado from Missouri 1863 and settled on a farm outside of Denver. 18-year-old Laps Ish came to Grand County in 1881 to attempt his luck at the short lived mining boom outside of Teller, north of Grand Lake. He tried his luck at mining for 4 years and also carried the mail between Teller and Grand Lake, on skis or snowshoes in the winter and by foot in the summer. Laps Ish married Alice Shearer and homesteaded near Rand (in present day Jackson County). They had two sons, Lesley John Ish and Guy Lapsley Ish. Laps and Alice built the Rand Hotel and operated it until 1910. The family then moved to Granby and built the Middle Park Auto Company garage and ran a stage line to Grand Lake. They built the Rapids Lodge by operating a sawmill on the Tonahutu River in Grand Lake and opened for business in 1915 They also built the Pine Cone Inn in Grand Lake and Leslie managed it for many years. Laps Ish died in 1943. |

| The Knight Ranch and Charles Lindbergh |

The Knight Ranch and Charles Lindbergh

In Grand County during the 1920's, you might have been lucky enough to have taken a plane ride over Grand Lake with Charles Lindbergh. It may sound preposterous, but Gordon Spitzmiller and his father, Gus, were two of the many fortunate people who got private sightseeing tours over the Grand Lake area with Charles A. Lindbergh as tour guide. In the early 1920's, the aviation industry was a brand new field open to the adventurers, the thrill seekers and the adventurous. Charles Lindbergh was one of those men. In the spring of 1926, Lindbergh had the dream of flying solo over the Atlantic Ocean, from New York to Paris nonstop. He was a determined man and was resolved to be the first man to cross the Atlantic and win the Orteig Prize. On May 22, 1919, Raymond Orteig of New York City offered a prize of $25,000 "to be awarded to the first aviator who shall cross the Atlantic in a land or water aircraft (heavier-than-air) from Paris or the shores of France to New York, or from New York to Paris or the shores of France, without stop." Besides Lindbergh, there were four serious contenders for the Orteig prize, one of which was Commander Richard Byrd, the first man to reach the South Pole. Lindbergh's courage and enthusiasm for such a flight were not enough; he needed financial backing. Lindbergh found his financial answer in Harry H. Knight, a young aviator who could usually be found bumming around the Lambert Field in St. Louis. This was the beginning of the Knight-Lindbergh partnership that would soon change the course of aviation history. After being denied any financial assistance by several of St. Louis's businessmen, Lindbergh made an appointment with knight at his brokerage office. Knight, the president of the St. Louis Air Club, was fascinated with Lindbergh's plan and called his friend, Harold M. Bixby, president of the St. Louis Chamber of Commerce. Bixby also displayed a strong interest in the obscure stunt flyer and mail pilot. Together Knight and Bixby formed an organization called "the Spirit of St. Louis", which was dedicated to gathering funds for the flight. More than $10,000 was needed in order to build a single engine plane and acquire the proper equipment. Knight went to his father, Harry F. Knight, who was a major power in the realm of finance and an equal partner in the firm Dysart, Gamble & Knight Brokerage Company. Like his son, the senior Knight was interested in the aviation field and backed every effort to make America conscious of airplane transportation. Without the financial aid and moral support offered by the Knight family, Charles Lindbergh may not have been able to cross the Atlantic in 1927. Lindbergh's gratitude to these two men never ebbed. Lindbergh and, his famous wife Ann Morrow, came often to Grand County as guests of Harry F. Knight whose ranch encompassed 1,500 acres on the South Fork of the Colorado River. The ranch today is covered by the waters of the Granby Reservoir. Knight, a nature lover, spent much of his time at this ranch. It was a haven for sportsmen and adventure seekers, and Lindbergh was a natural for these two categories. One of the largest and best airstrips in the west was added to the Knight Ranch in order to accommodate the owner and his guests. Besides the airstrip, the ranch boasted a miniature golf course, a 28 room estate, a private guest "cabin", a good selection of livestock and an array of entertainment that would suit all. It was a sanctuary for the affluent. Local people were so enthused about the handsome aviator that they named a 12,000 ft. peak in the Indian Peaks Wilderness Area (east of Granby) "Lindbergh Peak". However, during the 1930's the hero was honored by Adolph Hitler and Lindbergh made a speech favoring Nazism. This lead to a fall from grace in the eyes of the public. Even though Lindbergh changed his mind as World War II began, it was too late to regain his former popularity. The peak was renamed "Lone Eagle Peak" which was a nickname for the famous aviator. After Harry F. Knight died of coronary thrombosis in 1933, his son, along with ranch manager Harry Morris, turned the ranch into a major breeding and beef cattle operation. It continued as such until 1948, when the Knights were asked to sell it to the federal government or have it condemned to make way for the reservoir. Moss bought out the cattle operation and most of the buildings were sold, but the colorful memories of the Knight ranch were buried in the depths of Granby Reservoir. |

| The Norton Family |

The Norton Family

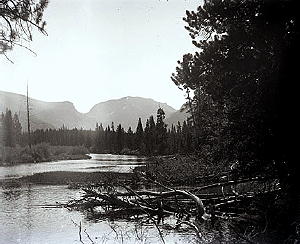

From his earliest memories, Mike Norton recalls playing with model ships and submarines with his older brother. His older brother had a ship, and he had the sub. The small pond on the Circle H ranch where he spent his early life before Lake Granby filled up gave little boys' imaginations an ocean. Marbles gave them depth charges. "But I could never find a way to shoot marbles from the sub," Norton laughingly remembers. As the water literally rose above his home, it shaped his life. The history of Lake Granby and the Norton Marina goes as deep as the water, literally. Grand County's pioneer ranching history lurks at the lake's bottom, sharing its place with rainbow trout amid the vast water supply for eastern Colorado and beyond. Before the lake filled up as part of the Colorado Big Thompson project, ranches like the Lehmans, Knights and Harveys had been stage stops, cattle and dude ranches and even an airstrip used by Charles Lindbergh. Mike's dad Frank came to Grand County to ranch. "All I ever really wanted to do first was to be a rancher here," Frank Norton told the Sky-Hi News back in 1997. At fifteen or sixteen years old, Frank Norton in a Model T Roadster traveled from Okmulgee, Oklahoma to Grand County, where he "fell in love" with the ranch that his mother and step-father started around 1930. The Circle H, started by his step-father Jim Harvey in the valley that is now Lake Granby, became his summer home. By all accounts, Frank Norton loved ranching. The Circle H "was a working ranch and a dude ranch." Harvey's ranch provided a spectacular backdrop highlighted by the Indian Peaks, reaching 13,000 ft high along the Continental Divide. The Circle H offered a caricature map for tourists looking for a real western experience. It led them over Berthoud Pass along hwy 40 to hwy 34 and then right at the Circle H sign to the Ranch. Leaving on horses from the Circle H, Frank Norton and Jim Harvey took them into a vast and remarkable country that, for the most part, can only be reached on foot today. In those days, the area now protected as the Indian Peaks Wilderness Area faced less threats from overuse. Ranchers hunted the region to supplement the sometimes skinny winter rations. "Jim Harvey shot two elk from his saddle," Mike Norton proudly recalls of his grandfather as we look at a romantic image of Harvey on horseback. Nowadays, quotas limit use through the peak season. The National Park and Forest Service restrict horse traffic and campfires as well. Early Harvey and Norton history highlight a different time and place, when the remote reaches of Indian Peaks could still be reached by trusting a cowboy with a Winchester rifle to get you there and back safely. For Mike Norton, the water that drowned out his family's ranching history also floated Norton Marina. Going from ranching to the marina business may seem an odd transition, but Mike's family history shows how flexible they were! Frank Norton spent his early youth traveling with his father's tent show, Norton's comedians. "Dad had such funny stories about that," Mike says. When the traveling troupe era ended (talkies and the Great Depression meant "they didn't eat too well sometimes"), Frank Norton moved to Oklahoma with his father before finally joining his mother and Jim Harvey in Grand County. Regardless of his occupation, Frank Norton was a showman. Remarkable old photos save the rich history of pack trips into the Indian Peaks area, camp sites on the shores Lake Monarch and rich harvests of rainbow trout. But Frank Norton and his horse Oak rearing high like the lone ranger really show Frank Norton's flare and charisma. In many ways, Norton Marina continued the Circle H's heritage. Frank's marina included the Gangplank, a restaurant and dancehall that looked like a boat, with porthole windows and originally a rainbow trout aquarium for the bar. His admiral's hat, which Mike still has today, replaced his cowboy hat and a 25 foot Chris Craft named the Bonnie B replaced old Oak as his ride. More or less, this is the world in which Mike Norton grew up. Growing up Frank's son meant work too. "I was 8 or 10 years old" when we started "Norton's Ark," Mike smiles, referring to the Gangplank restaurant. It was the early fifties in Grand County. "What backhoe?" No bailouts either! "Those first few years, I nearly starved to death," Frank Norton once told a reporter. "But," he added, "every year the business kept growing and before I knew it we had a good marina going." Before it was over, Norton Marina fulfilled Frank's dream of a family business, only in "boating recreation" instead of ranching! "It wasn't all roses," Mike agrees. As a boy, Frank Norton went to military school. "They disciplined him and he used the same technique on his kids." Frank expected his kids to help and to obey his commands, without question. Using Tide and a G.I. scrub brush, Mike Norton recalls scrubbing lower units. They painted wooden boats in the wintertime in the shop. The kids came in from school, changed clothes and started working. "Dad and mom had a lot of kids cause they needed a crew!" Maybe his most memorable job was cleaning out the septic tanks for the cabins that his dad built to help offset the lack of income at a Rocky Mountain marina during winter. After digging up the lids, "dad would put a ladder into the septic tanks." Then, Mike crawled in and shoveled out the waste while his dad hoisted the buckets out. "I was so glad when Ernie Seipps started his septic clean out business," Mike says as we motor along beside Grand Elk Marina's covered docks on a pontoon boat. The hard work and experience at the marina paid off when Mike joined the military. Like so many of his generation, Mike received his notice to join ground forces in Vietnam. Luckily, about that time, Navy recruiters were in Granby. They showed a strong interest in a National Honors Society student who lived a life on water! The pieces of the puzzle fit, and "that got me in the Navy," says Mike with real appreciation. In 1973, the family tradition passed on to Mike and his brother Frank when they bought the marina business from their dad. A lifetime of experience came with them. But it took more than dock maintenance, boat service and customer service to run Norton Marina. And, as the brothers took over, the old Admiral Frank Norton stayed in the house he had built next door to the gangplank, insuring that his strong personality was never far away. Lots of obstacles exist for a marina on public lands. As Mike took over sole ownership from his brother, he also fought to bring the marina under the National Forest Service instead of the National Park Service, which effectively removed the "power of condemnation." "We had to fight for our livelihood," Mike explained when he sold the Marina in January of 1997. Mother Nature challenged the marina too. Ice might remain on the water for half of May. June snowstorms blow in monster clouds, as awe-inspiring as the calm sunsets. Freezing rain rips into all but the best prepared boaters nearly any time of year, and hailstorms can hit in a heartbeat. "We're like farmers in that way," Mike recalled. "Drought, winters, high water, low water, you can't really help, we understand that." On the other hand, the glassy waters of Lake Granby reflect the awe-inspiring Indian Peaks along the Continental Divide on calm, sunny days. Tourists and locals try their luck catching the Mackinaw that makes it attractive to sportsmen and women. Intrepid wake boarders mix with sweet sailboats against a beautiful background of rugged peaks that reach high above tree line. On those days, it's hard to think of a more spectacular place. Through it all, Mike Norton clearly enjoyed his life at Norton Marina. "I liked being out in the elements with the boating public." He also counts the independence of self-employment and the uniqueness of the marina as blessings in his "good life." Grand Elk runs the marina today (2009). Its operation rents out slips and moorings, daily pontoon boats and other related services. It's as beautiful as ever to peer across the lake at sunrise in August, and it's as cold and forbidding as ever when the winter winds whip across the thick ice an snow of the lake in January. Few wooden hulls appear during summer season as in the old days, but beautiful boats, both motor and sail, still surround the Marina. Yes, its original character remains, not far from the surface. The Gangplank changed its name to Mackinaws, where customers in the main room still look out portholes across the lake to the rugged outline of Indian Peaks Wilderness Area, although there is no longer as much space on the dance floor. Those familiar with Indian Peaks recognize old Abe Lincoln lying in his grave along the Continental divide, where Mike's early ranching family led pack trips and today can still be reached, albeit under more controlled circumstances. Today's anchored concrete docks and gas dock continue the process that started with Frank Norton using finger docks that Mike staked in the ground and an old chicken coup from the Circle H to fuel boats. And in all of Grand Elk Marina's features and history, Frank Norton and his family exist. In the house that they built on site where all of his children were photographed as they grew up and as they graduated from Middle Park High School. In the restaurant where Mike remembers finding the nerve to ask pretty young gals to dance. And, in the numerous family photos that show a smiling, handsome Frank Norton and his attractive family surrounded by high mountains, wooden Chris Craft and a sense of high expectations. Mike remembers his dad as the "greatest storyteller I've ever known," which he used to his advantage in all occupations. In 2001, I met Frank Norton, only once before he died the next year. He told us about the time Jim Harvey knocked the federal agent who came to tell take their land away to the floor, placed a foot on his chest and said, "If you get up, I'll knock you down again." We could see it happening as he told the story more than 50 years later. But the story continues beyond Frank Norton. From traveling tents shows to dude ranches to a forty-plus year family run marina, the Nortons made one of Grand County's most enduring "institutions." Entertaining, industrious, and life-loving, Mike simply says, "It's been a really good life." And that's a family tradition. |

| The Ute Legend of Grand Lake |

The Ute Legend of Grand Lake

A group of Utes were camping on the shores of Grand Lake when they were suddenly attacked by an enemy tribe of the Arapaho (and in some versions the Cheyenne as well). As the brave Ute warriors began fighting, the women and children were hurried onto a large raft for safety and pushed to the middle of the lake. As the battle continued, a treacherous wind overturned the raft and all the women and children were drowned. Many Ute warriors were also killed during the fighting. The legend holds that you can still see ghostly forms in the morning mist rising from the lake and hear the wailing of the lost women and children beneath the winter ice. The Utes avoided the lake for many years because of these tragic events and evil spirits. |

| Ute Bill Thompson |

Ute Bill Thompson

, ,

William Jefferson (Wm./W.J./Bill) Thompson was born on March 26, 1849 in Aurora Township, Preston County, Virginia (1863-West Virginia). The 8th child of 9 children of Wm. & Mary Anne (Wotring) Thompson. His father was a shoemaker at the Wotring Tannery and died in 1853. Mrs. Thompson left Preston County in September 1859 with her children on a covered wagon for Oregon. They arrived at St. Charles, Iowa around Christmas, settling at New Virginia, joining other relatives. Once, the Ute Indians saw him baking biscuits and they enjoyed the “beescuts” until the flour ran out. An altercation left Wm. severely beaten. He made his way to Georgetown and the miners denied him entry, thinking he was a crazy man. One kind miner gave Wm. canvas for clothing, and took him to Idaho Springs. He recovered and was employed as a shoemaker. Wm. re-entered Middle Park, built a hunting cabin on Muddy Creek ready for the 1867 winter. Chief Yarmonite led 40 Ute men, women and children to Wm’s cabin explaining to him that the Gore Range was covered with snow, and they were in need of food. This time Wm. refused. A rifle match was agreed upon with the loser put to death. Wm. threw his sombrero to the ground as his hair fell to his shoulders. A cry of the Ute went up as they recognized Wm. from the Troublesome. Sub-chief Piah told Wm. they could not fight a Ute brother, and braided Wm’s hair and applied face paint as they were at war with the Arapahoes. A hunt for bison began. Shooting was heard with the thought the Arapahoes arrived. Len Pollard & Sandy Mellon were chasing buffalo, which Wm. shot and killed. Len & Sandy confronted the supposed Ute with Len asking, “Where did you get Bill Thompson’s Winchester rifle?” Wm. played along until Sandy aimed his rifle on Wm. who wisely said, “Don’t over reach yourself, Sandy.” Sandy demanded, “Who in the hell are you!” Bill laughed and told them he was Bill Thompson. The sobriquet of “Ute Bill” was given. Wm. preferred his nick name over his legal name. This article is dedicated to Lorna Marie Gowen; September 6, 1954-April 14, 2006 |

| Ute Bill Thompson and His Memorial Marker |

Ute Bill Thompson and His Memorial Marker

Dark clouds covered the Continental Divide as we looked east from the ridge leading toward Elk Mountain's remarkable view. Cool winds and spitting snow followed us. We weren't seeking the height of Elk Mountain, but instead, were tracking the historic path of Grand County Pioneer William Jefferson "Ute Bill" Thompson. Specifically, we wanted to locate the memorial marker for Ute Bill that Henry Grafke and Otto Schott placed along this ridge after Ute Bill died in 1926. Tracking Thompson requires divergent paths. On one hand, Ute Bill's early presence in Middle Park places him in an era when mountain men and Ute Indians shared the vast herds of elk and deer. Only a handful of hardy souls called Middle Park home when Bill Thompson arrived in the late 1860s or early 70s. On another hand, Thompson settled just east of Hot Sulphur Springs as a young man, where he carved out a cattle ranch that remains in his family today. Records prove he owned and operated a billiard hall, drove stagecoaches and established a homestead along the Colorado (then, the Grand) River. But tall tales and oral legends abound too, capturing hair-breath escapes, harrowing western adventures and the mischievous nature of a 19th century westerner. Looking through the numerous historic photos of Ute Bill at the Pioneer Village Museum in Hot Sulphur Springs leaves an impression of a capable trapper, businessman and rancher who textured his image with stories of western adventure. With Don Dailey - fellow historic trekker and great grandson of Ute Bill - along, I hoped to pursue the fact and folklore of Ute Bill. As Don pointed out an isolated cabin in the valley below, a Ute Bill tale from the Georgetown Arbitrator of September 1886, "as narrated at the time by one of the participants," captured my imagination. Bill Thompson breathed a sigh of relief. The rugged, hungry band of Ute in front of him smiled approvingly as his long black hair fell from his broad-brimmed black hat. A tense moment before, he'd worried about his future as the small band of Ute Indians led by Yarmony came upon his isolated cabin in Middle Park. Fact is, Bill Thompson's hair had just saved his life. Not bein' cut since the Sioux captured him as a child, it hung nearly to his waist. Bill was all set up for a Middle Park Winter, with supplies to last through the toughest stretch, when Yarmony and his band came along. Thompson cursed softly at himself for not payin' closer heed to their approach. "Figured they'd be out west by now," Bill muttered as he squared up to his guests. Speakin' through a mix of hand signs, broken Ute and English that most fellers in the mountain parks west of the divide understood well enough for basic communication, Bill impressed the band with his manly firmness and calm self-confidence. Then Yarmony spoke, "Beescits," was all he said. Bill hesitated to open his cabin supplies. "Why, them folks are so hungry," he thought to himself, "they're near certain to go mad if they laid eyes on my bacon and flour." At best he'd be without supplies at a risky time of year. "No biscuits, fellers," Bill said with as much certainty as he could muster, "barely enough food fer myself. There's still a shaggy buffalo er two fer the takin' and every feller's got the same chance." When Bill finished talkin' he looked Yarmony square in the eyes. He watched the headman's leathered face swing toward his rough-sawn cabin door thoughtfully. "Beescits," he repeated. Yarmony's band, snuggled in their elk skins and trade blankets, looked stoically at Bill. "Well," Bill said, throwing down his last ace, "seems you're intent on havin' my grub and I'm intent you ain't." Then, regrettin' it before he finished sayin' it, Bill raised the stakes, "Why don't we have us a shootin' contest fer it?" No immediate reaction caused Bill to wonder if he'd communicated clearly. Slowly, though, excitement spread through the crowd of Ute, as the entire band - from the pretty young girls to the big-bellies - looked to one feller. In front of Bill stepped a mountain-sized-Ute feller, creating a shadow as he approached. "Piah," the Ute whispered, breaking into a quiet chaos of conversations. Movin' quick and hopin' for some break, Bill scooped up his improved Winchester rifle as he threw off his broad-brimmed black hat so nothin' could obstruct his shootin' eye. Just as soon as his long black hair fell near his waist, the tense moment ended with a gasp from the Ute, followed by a welcome reception that meant more to Bill than any he recollected! Bill determined then and thar on never cuttin' his hair again! As he eased down the gun smilin', all them pretty Ute girls began paintin' his face and braidin' his locks. Bill was feelin' positively giddy about his good fortune. Decidin' he just might owe these hungry Utes a favor fer endin' a potentially tragic shootin', he led 'em to a nearby ravine where he'd been watchin' a small herd of shaggy buffalo. Now Bill Thompson figured he'd repay 'em with meat, and still keep his own supplies. Leavin' the Ute on a rise above the ravine, he sauntered down to the fresh buffalo trail just as he heard the thunder of hooves around the ravine's bend to the south. Settlin' into a remote stand of lodge pole pines, he sat right along the path of the rumblin' bison. Pickin' out his choices as they rounded the bend, Bill's Winchester boomed repeatedly, each shot bringin' down a fat cow or a young bull. Swaggering toward his kills, Bill was suddenly confronted by Sandy Mellon and Len Pollard, sneakin' along that ravine behind the buffalo. Not recognizin' Bill through all the paint and braids, Sandy thundered to Len that this Ute feller must "a stole Bill Thompon's gun," because there weren't many repeaters like his. Both their guns were trained on Bill. Calmly, Bill broke the silence. "Don't over-reach yourself, Sandy." Yes sir, Sandy knew from the voice that this-here Ute feller in front of him was really Bill Thompson. That day, he became Ute Bill. Breathing hard to make the final incline, Don and I reached the point along the ridge of Elk Mountain where we expected to find the memorial. There it was, as we had hoped. After a hurrah for our success, we slowly read the plaque: "Hunting Grounds of "Ute Bill.'" As we snapped photos and drank water from our packs, I decided that where historic fact and local folklore meet, an authentic western tale begins. |

| Ute Legend of Canyons |

Ute Legend of Canyons

|

| Ute Legend of the Quaking Aspen |

Ute Legend of the Quaking Aspen

It is amazing to behold the continuous quivering of aspen leaves in groves around Grand County, even when there is no apparent breeze. According to Ute legend, the reason for this unique aspect of the aspen tree happened during a visit to Erath from the Great Spirit during a special full moon. All of nature anticipated the Spirit's arrival and trembled to pay homage. All except the proud and beautiful aspen. The aspens stood still, refusing to pay proper respect. The Great Spirit was furious and decreed that, from that time on, the aspen leaves would tremble whenever anyone looked upon them. |

- ‹ previous

- 6 of 7

- next ›