Community Life Articles

| Skiing |

Skiing

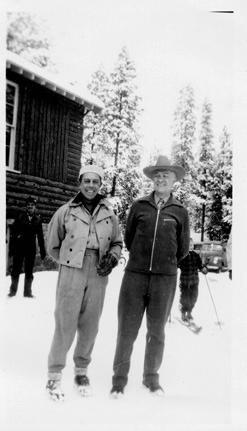

Grand County was one of the first areas in Colorado to enjoy sport skiing. While mail carriers, loggers and other workers used the "Norwegian Snowshoes" as necessary winter transportation, it was a natural progression to begin racing down the slopes for fun. An 1883 newspaper noted that in Grand Lake "Coasting on snowshoes has taken the place of dancing parties. Quite a number of ladies are becoming adept at the art. First class snowshoers, B.W. Tower and Max James are the best; or at least they can fall more gracefully then the rest". According to famous Hot Sulphur Springs champion Barney McLean, that town had three jumping hills in the 1920s and held the first Winter Carnival in the West there in 1911. By 1925, Denver sent special "snow trains" there for the recreating tourists. Skiers such as Bob McQueary and Jim Harsh competed in statewide events along with skiing "veterans" Horace Button and McLean. Grand Lake's Jim Harsh became the first Coloradoan to qualify for the U.S. Olympic Team. In 1932, the Grand Lake Ski Club held its first winter sports week on Denver 25-January 1st. Featured was a motor sled with an airplane engine which pulled skiers over the frozen lake are speeds of 90 miles per hour. Colorado's first ski tow was opened at the summit of Berthoud Pass in 1936. Berthoud Pass operated on and off throughout the next 60+ years but was finally closed and the lifts dismantled in 2002. What became the resort of Winter Park featured skiing at the West Portal of the Moffatt Tunnel and the Winter Park Ski Area opened as a result of efforts by Denver Parks & Recreation Director George Cranmer. Early lodging resorts in the area, then known as Hideaway Park (now Winter Park), included Sportland Valley, Timberhaus Lodge, and Millers Idlewild Inn. Eventually trains made daily runs to Winter Park, loaded with intrepid skiers. Steve Bradley invented the first effective snow packer on the slopes of Winter Park. With a strong record of winning high school ski teams, Grand County accounted for a remarkable number of skiers who later took park in FIS (International Federation of Skiers) meets and U.S. Olympic teams. |

| Sounds of Christmas |

Sounds of Christmas

Contributed by Vera "Stathos" Shay, Kremmling A blast from the past A frosty night in December A wonderful time to remember Fun on a hay ride My husband at my side Friends young and old Dressed for the cold A pickup truck Praying it wouldn't get stuck Snuggled together in the sled of hay We were on our way Our hearts and voices filled with song From our Christmas caroling Kremmling did ring Everyone could hear Us ringing Merry Christmas cheer.

|

| Spider House Tragedy |

Spider House Tragedy

Nestled on a quiet lane in Old Grand Lake City sits the intricately crafted home of Warren C. and Mary O’Brien Gregg, known today as the Spider House – a testament to a remarkable woodcraftsman and his tormented wife. Warren (Watt to his friends) was a dreamer and in the 1870s he left his first wife and a young son in Wisconsin and headed for the Colorado Territory seeking his fortune in the mines of Gilpin County. Upon returning to Wisconsin his first wife died of fever, leaving Warren a widower with a small son. Holding tight to his dreams of the west, Warren eventually ended up in his native Indiana where he met and married 20 year-old Mary O’Brien, in 1884. By 1888 Warren packed his new family into a prairie schooner and headed west. Like so many other pioneer women before her, Mary bore a child along the trail, a second son whose short life would send Mary down a dark and tortured path. The family arrived in Middle Park late in the summer of 1888, built a small homestead on the eastern slope of the Stillwater drainage and the newborn died shortly thereafter. Though the years would bring more children, Mary would never quite recover from the loss of her second son. They continued to scratch out a living in this harsh and isolated land, where winters were long and supplies were meager. Warren spent much of his time searching for game and exploring this new country. The Gregg’s moved numerous times, finally purchasing a plot of land from Old Judge Wescott on the west side of the lake. Warren built his family an admirable house, with intricate detail and spider-like webs of wooden elements. Despite the warmth and comfort of this new home, and the close proximity of neighbors, Mary’s depression deepened. Then on a sunny Sunday in 1904, while Warren was working in his woodshop and oldest son Lloyd was having Sunday dinner at Judge Westcott’s, Mary took a gun to her four remaining children and then turned the weapon on herself. The children died instantly while Mary lingered on for four days. The five victims of this tragedy, one girl, three boys and Mary herself are buried together in one grave in the Grand Lake Cemetery. Warren lived in the Spider House for another 29 years. With his son Lloyd, he continued building homes and stone fireplaces. He succumbed to heart failure in 1933. Mary O’Brien Gregg finally found peace in the quiet grace of the little town cemetery surrounded by her children. Almost a century later, as the tall pines whisper their mournful winter song, the Spider House still sits nestled on that quiet little lane. |

| Sudden Death in Old Arrow |

Sudden Death in Old Arrow

A shooting in the Old West I know was not much like the shootings on television today. There was no glorification of the bad man. Killings were usually like the fatal shooting of Indian Tom on that 6th of September, 1906, in old Arrowhead (or Arrow). Nobody called anybody out. Nobody told anybody to draw or asked him if he was wearing a gun. It wasn’t a fight. It was a killing. 1906 Arrow had six saloons, a grocery store, one small hotel and a livery stable. But two thousand people picked up their mail there. The woods were full of tie-hacks: the three sawmills hired may lumberjacks and teamsters, most of them Swedes, who seemed to make the best lumbermen. I had arrived in Arrow the 18th of April that year to work as a teamster for my brother Virgil, who had been operating a sawmill there for about a year. I was just sixteen. My brother Dick, the tallest Lininger, had been Virgil’s foreman. Virgil had also bought the only hotel in Arrow. My mother, two sisters and my little brother Gilbert and I came from our farm in Osawatomie, Kansas, so that my mother could run the hotel. My brother Wesley came at that time too: he planned to buy a lot and build a café. Whole families often followed the first member who had come to these early Colorado towns. I soon discovered that driving logging horses needed a lot more technique than driving a small farm team, but Virgil was patient, and I soon received a raise to $2.75 a day as top teamster. The town was a wide open as it could get. My first introduction to the violence was the day my brother Dick fired three drunken lumberjacks. They drew their pay and went to Graham’s saloon to get drunker. As dick passed the saloon later, one of the men grabbed a quart whiskey bottle, and ran out and struck Dick behind the ear, knocking him cold. The three then proceeded to kick him around. Dick’s roommate Charley came to my brother’s rescue. When Dick came to, he started for the hotel. Charley guessed what he was after and beat him to the six-shooter. “I’ll make sure you can taken them one at a time” Charley promised him. I came along just as my brother knocked the pick from the pick handle. Something was up! In less time than it takes to tell it, Dick had three drunks out cold. Mother patched Dick up. I think this was her introduction, too. A man couldn’t stay boss long if stayed whipped. Every other Sunday was a holiday for me although I always saw to it that I put in enough overtime to bring my monthly paycheck to $75. That September Sunday I was dressed in my holiday garb – tan peg-top dress corduroys, light blue wool shirt, Western hat, and high-laces boots as befitting a teamster who drove four or six horses hauling logs from timber country to the saw mill. When I drove six horses, I rode one of the wheel-team horses and held the lines over four. If I drove four horses, I rode the wagon and sat on a sack of hay. About noon, I stopped in front of the MacDonald saloon to talk to Ed MacDonald, one of the few saloon men my mother didn’t disapprove of. After all, Ed had come to Colorado as a TB and couldn’t do heavy work; filling glasses over a bar was about the only light work in those old mountain towns. Later Ed owned the famous MacDonald Ranch on the South Fork of the Grand Rover – now Colorado River- and managed boats on Monarch Lake just above his ranch. He always served great dinners and good food. While Ed and I were talking, Indian Tom rode up. He was a flashy cowboy of the old school, a very good looking man with predominantly Indian features although he was only half Cherokee. When riding, Tom always wore leather chaps, spurs, and a big Stetson. As wagon foreman for Orman and Crook, contractors for building the Moffat Road, he was a very important figure, for he had charge of all their wagons and teamsters. The greeting between Ed and Tom was cordial. Everyone liked Indian Tom. When Tom learned I was a teamster for my brother Virgil, Tom showed a much keener interest and invited me in to MacDonald’s for a drink. Ed rescued me. “Oh the kids doesn’t drink; but he might like a cigar”. As they ordered drinks, I puffed away in my best imitation of a Kentucky colonel; however I soon excused myself, saying that I had to target my 30-30 rifle for the upcoming deer season. I puffed until I was out of sight. The corn silk I had scorched behind the barn paid off. I didn’t disgrace myself, nor had I broken my pledge to my mother not to gamble, use profanity, drink, or perform any act inconsistent with the conduct of a gentleman. I took my rifle northwest of Arrow to Fawn Creek. It was a beautiful fall day. The aspen were just beginning to turn. Fawn Creek Gulch had been burned over many years before by the Indians who hoped in this way to discourage settlers, and the aspen were all young, straight and shimmering in the way that has never ceased to delight me. The fire thirty years before had made the gulch an excellent place for deer hunting because the new growth gave the deer some inviting protection, but the terrain was open enough for a hunter to locate his game. I figured I’d have to shoot from at least 200 yards, so I planned to target for that distance. I tacked a piece of cardboard I’d cut from my brother’s Stetson hat box (he never took off his Stetson off anyway) to a tree and stepped off the 200 yards. That 6-inch target looked pretty small but after each three shots, I’d examine the target. Finally satisfied, I took a long walk looking for deer sign, tracks, or droppings. I found good sign but no droppings. About feeding time for the horses, I went back to the barn in town to feed the four, Cap, the big bay, Bird, the glossy black (those were my two wheel horses- t e ones next to the wheel); Kate, the little lead horse; and Bud, her mate. Virgil had bought Kate, a grey mare weighing about 1400 pounds, at a very reasonable price from the Adams Express Company because she had run away at every opportunity and had destroyed several wagons. He couldn’t run away now pulling Cap, Bird and a load of lumber with her, but her high spirits made her an excellent leader. The heavier team, always used as the wheel team, weighed about 1700 pounds each. I was very proud of this unusually fine team. Virgil had trained Cap and Bird so that after they were harnessed in the barn, they could be turned loose to go to the watering trough, drink long and thirstily, then walk out to the wagon, back into position by the tongue, and stand ready to have the breast straps snapped in place and the tongue attached. When tourists trains stopped and hundreds of passengers stood around the eating places looking the town over, I’d drive slowly by, and then stop to rest the team a minute, to give the dudes a chance to see a good, four-horse team. Then with a single “Yup!” I’d pull all the lines tight, and they’d start as one horse while the tourists explained and pointed. That Sunday after I put a gallon of oats in their food box and shook some hay into their manger, I left the barn and started up the steps alongside the depot. It was still light; the sky hadn’t even begun to color. Time to head home for supper. I’d have to be up, hitched and pulled by seven the next morning. We’d probably have roast beef or roast chicken with noodles, since it was Sunday. Mother would be cooking on the big wood-burning stove at the hotel, and my sisters would be taking the heaping platters to the tables where everyone would pass them around. Probably there would be hot biscuits. Suddenly a shot cracked just above me and across the street. I knew instantly it had come from the Wolf Saloon ahead. It wasn’t common to hear shots in those days. You hear more in a 20-minute Western on TV than you heard in a couple of years unless a few boys rode into town on a Saturday night to shoot up the air. I broke into a run and could see a man lying on the board walk in front of the saloon. As I got to him, one of the ladies I wasn’t permitted to mention came out and fell to her knees beside him. Raising the man’s head, she tried to pour whiskey down his throat. With a queer, paralyzed feeling, I realized it was Indian Tom. I reached for his wrist. His hand was warm as life, but there was no pulse. Several men ran our. “Ragland got him!” one of them shouted. We carried Tom’s body into MacDonald’s and laid him on a roulette table that was in the back room for repair. Somebody went to wire for the sheriff at Hot Sulphur Springs. Word soon reached Orman and Crook’s, and the Indian’s many friends began to jam into Arrow. Indian Tom and Ragland had evidently had words during the afternoon and had quarrels once more before at a rodeo. The women from the saloon said that when Indian Tom left after the quarrel, Ragland had stationed himself, gun in hand, inside the saloon door. Everyone agreed that Ragland knew he wouldn’t have had a chance in a fair fight with Tom. The moment they heard Tom’s spurs outside , Ragland pushed the door slightly open and shot point blank through the aperture along the hinge. The he ran out the back door. We searched the town inside and out for Ragland. The sheriff joined is in the search late that night, but we found no trace of him. Just after midnight a wire came for the sheriff. Ragland had turned himself in at Hot Sulphur. We learned later he had run to a ranch down below, borrowed a horse and ridden for his life. A coroner’s jury was called. My brother Virgil, named foreman, took a firm stand. The only verdict he intended to take out of that room was murder, and, after only a few hours, that was their verdict. After three days, Ragland was released on $3,000 bond posted by his father, but you may be sure he didn’t show himself around Arrow. His attorney, John A. DeWeese, got a change of venue from Grand County to Jefferson County at Golden, claiming an article in the Middle Park Times of September 7, 1906, reporting the verdict of the coroner’s jury, made it impossible for Ragland to get a fair trial in Hot Sulphur. The article said in part: Four witnesses for the prosecution, and seven for the Defendant were examined, making eleven in all. The testimony of the witnesses on both sides failed to show that the shooting was justifiable. According to the testimony, the fatal shot was fired when Reynolds (Tom) had his revolver in his scabbard and when he did not even see Ragland who was standing opposite the cut-off. (As told to Donna Geyer by A.W. Lininger) |

| The End of Texas Charlie |

The End of Texas Charlie

Article contributed by Abbott Fay Charles Wilson, a punk nineteen year old, came to One day in early December, 1883 the gang invaded a saloon in Hot Sulphur Springs and threatened the life of the barkeeper, then went to a general store and pistol-whipped a randomly chosen customer. Threatened with arrest, Charlie challenged the local constable by tearing up the warrant. The hoodlums left town but chose to return on December 9th. They dismounted at the Justice of the Peace office and drew their pistols. Suddenly, Charlie's revolver was shot out of his right hand and his buddies pulled back. When the kid from A post-mortem investigation was held and everyone admitted hearing gunfire and seeing the body, but no one knew which of the "leading citizens" of the town had fired. The jury returned the verdict: "We find that said C.W. Wilson came to his own death by gunshot wounds at the hands of some person or persons to us unknown". His partners had left town and were never seen again in Hot Sulphur Springs. The kid from Source: Robert C. Black,

|

| The face of the 1883 Grand Lake Commissioner Shooting |

The face of the 1883 Grand Lake Commissioner Shooting

By Amy Ackman Project Archaeologist - 2018 I work in Cultural Resource Management (CRM), which means I document any man-made occurrence that is 50 years or older. I’ve recorded anything from prehistoric stone tools to 1940’s cans and glass. As a CRM archaeologist, I’m a data collector. Our job is to protect the archaeological record by gathering data and determining the significance of it. In 2011, I worked on a project near Jensen, Utah, just across the border from Colorado. During this project, I came across an unmarked grave. There was a headstone, but no name. I eventually found from historical documentation that the grave was that of a man named William Redman. Redman was the undersheriff who took part in the Grand County Shooting of 1883 that involved three county commissioners, a county clerk, and the sheriff. Three men died during the shootout, two men died of their injuries after the fact, and the sheriff committed suicide out of guilt. Two weeks after the incident, Redman was the only living participant. He was on the run from the law and actively hunted by the Rocky Mountain Detective Association. A full month after the shootout, Redman was found dead in Utah at the side of a road with a bullet in his head. I knew Redman was part of the Grand County Shooting and poured over any sources I could get my hands on; books, websites, newspaper articles; any tidbits of information that might answer questions. Like a detective, I wanted to understand how Bill Redman was involved in the gunfight and how he ended up in Utah. I found the story and a picture of William Redman and I was ecstatic that a site I had recorded was associated with such a tale. William Redman was ruggedly handsome with high cheek bones and pronounced jaw; the clothes and countenance of a miner. The more I learned about him, the more questions I had. How old was he when the photo was taken? At a time when it was such a privilege to have a photo taken, why is there a photo of him and not other prominent men in the county? I wondered about his motivations. Was he the ruffian newspaper articles touted him to be? Archaeology is about understanding the past. Most of the time we are forced to interpret the past with only a few pieces of material that are left behind. The more material and data we have, the more we can understand. In the case of William Redman, there are questions surrounding his death that give rise to the possibility that the man in the grave is not Redman at all. If the opportunity arises to excavate the grave, his photograph will assist in his identification. Archaeology not only studies the past but works to preserve the past for the future. Now, I hope that a family member of yours is never being researched by an archaeologist for being a ruffian and a murderer. But, like an archaeologist, I would encourage you to preserve as much as possible for those in the future who would care to learn about the past. |

| The Great Kaboom |

The Great Kaboom

Article contributed by Jean Miller Bill Cullen moved to Hideaway Park from Berthoud Falls in 1961, at which time he bought several pieces of property. One was the filling station and the Village Inn, priced at $25,500, belonging to Wally and Dottie Tunstead, who had come to town right after the war. The Tunsteads moved back to Oklahoma, their former home. Behind Tunsteads’ stood a very small, old house, on land possessed by Easy Butler; Bill bought this too, in 1963, as well as a house near Vasquez Creek, owned by an old-timer, Charlie Tigges. Next he bought old Mrs. Zeida’s house; she had died in 1964, and when her son Joe came to clear it out, Bill hightailed it over to see him. “I’d like to buy your place. Would you be interested?” Joe was definitely interested, so the two came to an agreement on the price: $100 down and $50/month. Adjacent to this was land belonging to Marie Roth, which Bill had already bought, and the Roth/Zeida properties formed the nucleus of Bill’s “homestead.” One of his first projects was to put in an access drive to the house, for there was none. Few of these people drove, you see. Almost immediately Bill discovered that there was a huge rock in the way, one which wasn’t going to be moved with just a pick and shovel. Wandering over to see his friend, Dwight Miller, he inquired, “Did you by chance have any dynamite left over after blasting those beaver dams the other day?” “Why, as a matter of fact, I did,” answered Dwight. “What do you need?” Thus it was arranged for Dwight to come blast that rock out of there. Now Bill’s driveway was to be built along the very edge of his property, which also happened to be very close to the home of Mrs. Hart, who lived with her son, Ken, and his children, Beverly and Danny. Bill and the Harts always had a running battle going. He had gotten cross-wise with Ken, when he blacktopped the road in front of the Village Inn filling station, thinking to make it easier for customers. Because Bill and Dwight were friends, by extension, Dwight was also Mrs. Hart’s enemy. Mrs. Hart was a crusty old gal and when she saw that something was a-foot, she hustled out to protest. “You two’ll have holes knocked in the roof of my house with all that blasting! You can’t do it.” Bill thought a moment. “I see your point, Mrs. Hart. I tell you what. I know where there’s an old mattress. We can put that over the rock and it will contain the sound as well as odd rocks that might go flying.” So Bill and Dwight headed down to the little house behind the Village Inn. It seemed that some fellow was renting it from Bill and he hadn’t bothered to pay his rent, minimal as it was, for at least four months! Without a qualm, the friends brought back a rather ratty mattress that would do the trick perfectly. Dwight dug down next to the rock and carefully stuck his sticks of dynamite around it. They laid the mattress over the top and placed the fuse leading away from the rock. Mrs. Hart stood, glaring at them from inside her house. The moment had come. Dwight lit the fuse and the two men ran off to a safe distance. A few moments later --- KABOOM! Dwight and Bill saw the mattress rise and rise, higher and higher, up to the very tops of the nearby pines. They heard the rattle and clatter of small rocks tumbling and skittering off Mrs. Hart’s roof. They watched that furious old woman rush from her house with fire in her eyes, almost before the mattress had a chance to make a safe landing. She was ready to tear them limb from limb! But they checked her roof, and amazingly there was no damage at all. What a bit of good fortune. They inspected the rock and found that it had shattered beautifully! Bill would have no problem at all in building his road now. Dwight did earn from this project, however, that there were some things he didn¹t know about blasting rocks! As for the mattress, they searched for it. I can assure you that that mattress was never going to look the same again. Off to the dump it went, at least those parts of it that could be found!

|

| The Middle Park Band and the Music Man |

The Middle Park Band and the Music Man

The Middle Park High School band wasn’t much to brag about, and that’s a fact. Several members were very capable young musicians, however. For instance, Stuart played a hot set of drums that set people’s feet to tapping and hands to clapping. Debbie was an excellent trombonist, good enough so that one year, she was invited to march with Pierre Laval’s All American High School Band in the Rose Parade! And Jack was right behind her in skill. Martha led the flutes beautifully, and there were Alan, Bert, Roxanne, Carolyn, and others. But the group never seemed to coalesce into a single playing unit. |

| The Mighty Forty |

The Mighty Forty

Article contributed by Jean Miller The Middle Park High School band wasn’t much to brag about, and that’s a fact. Several members were very capable young musicians, however. For instance, Stuart played a hot set of drums that set people’s feet to tapping and hands to clapping. Debbie was an excellent trombonist, good enough so that one year, she was invited to march with Pierre Laval’s All American High School Band in the Rose Parade! And Jack was right behind her in skill. Martha led the flutes beautifully, and there were Alan, Bert, Roxanne, Carolyn, and others. But the group never seemed to coalesce into a single playing unit.

Then a Music Man came to the school. Wes Robbins was a showman; he was enthusiastic; he had flare; he had color. He took those young people in hand and soon had them marching in time down the same street. People flocked to hear the music, whereas before, they just groaned. By the end of the school year, Mr. Robbins decided that the band needed uniforms, sharp uniforms to match the cool music. Now most of the extra-curricular funds went into sports, particularly football. But the band leader convinced the administration that with uniforms, the band would rouse the fans to a high pitch, encourage parents and family to attend games, incite the teams to greater, and winning, efforts. So he got the uniforms. That fall the band players tingled with excitement as they waited to try on their new duds. They looked wonderful. All the effort was worthwhile. But Mr. Robbins didn¹t stop there. Every spring, on the first weekend of May, Canon City held a Blossom Festival. Bands from all over the region came to march and compete. The Middle Park Band proposed to join this event! You must understand, there were only forty students in the band, for this was a small district still. When the youngsters arrived in Canon City, they met bands from Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska, as well as from New Mexico and numerous Colorado schools. Many of these bands had 100 to 120 or so members! All were much larger than our little group. The Middle Park students felt rather overwhelmed. But it wasn’t long before the big bands had adopted this nifty minuscule band as a mascot. Saturday came and the bands lined up at the foot of the Canon City prison wall. Just then, two inmates jumped from the top of the wall, presumably planning to escape into the mob of students and onlookers. Prison guards shot the men dead in the air. This rather rocky start for the event didn’t phase the boys and girls; the parade commenced. Grand County enthusiasts lined the edge of the avenue as the bands marched down, drums beating, horns tooting, and music filling the air. “But where is our own band?” they wondered. Suddenly, applause erupted and you could see why. A Nebraska band of some 120 members filled the street. Shortly after, striding bravely along, a compact band of forty students in spiffy navy blue uniforms, played beautifully and vigorously. Following behind them was another band of over 100 members. The contrast was astounding and people loved it! Clapping onlookers whistled and shouted. That afternoon the many groups competed on the football field, doing intricate formations as they played their music. Middle Park picked up two first place ratings for their performance that day. That was truly a triumph for our musicians, as they realized that even though they were small, they were mighty. This must have been about 1971. |

| The Millers Build Idlewild |

The Millers Build Idlewild

Article contributed by Jean Miller In June 1946, the C.D. Miller family broke ground for Idlewild Inn in the small village of Hideaway Park, Colorado. Although WWII was over, materials were still very scarce. What could be obtained locally was bought. Much was brought from Wichita, Kansas, where the family lived. By 1948, the rustic Inn was up and running. It had the charm that comes with the scent of pine wood, cozy fires, hearty food, friendly hosts, and total relaxation. Sons Elwood and Dwight managed the business, with the vital assistance of parents and friends during the Christmas season and summers. Elwood married after graduating from college and bit by bit, he gravitated to the teaching world, leaving Dwight to deal with eager guests. Idlewild Inn became a popular spot, especially families for seeking simple vacations. However, after a few years, the Millers realized that there was developing a desire for more sophisticated lodgings. About 1952, Dwight and his bride Jean had the opportunity to buy 160 acres of land across the valley, to which was later added 40 acres from a mining claim. The price was $10,000 and the couple wondered how they ever would pay for it. Nevertheless, this chance was too good to miss. The property extended far into what is the main portion of town today, across the railroad, and along both the Fraser and Vasquez Creek. A pleasant lane wound through the forest from the highway to the creeks and broad meadow. One step led to another. Dwight chose one-of-a-kind heavy, 4 foot thick cedar planks for the walls of his new lodge. He nestled the building into the "vee" of the valley flowing down behind. By Christmas 1957, Dwight and Jean opened by far the finest lodge in the area. Each bedroom had two double beds and a private bath with ceramic tile, a first in the area. The first full bar in the lodge was much appreciated by guests on cold nights. A few years later, Dwight built a year-round outdoor swimming pool, the first in the county. (It took as much coal to heat the pool as to heat the lodge itself.) Guests loved it, for in winter, they came from a day of skiing, jumped into the pool for a swim, ran to the steam room (also a first), and finally took a snooze before evening festivities began. Dwight was the first in the area to use a school bus for transportation to and from the ski area and in summer, to take people on trips within and out of the county. The realization grew that a beginners' area close at hand would be a great attraction, especially for mothers who found the trails at Winter Park daunting. They could bring their children to Ski Idlewild to learn to ski, brush up on their own skiing, and when tired, go into the lodge to relax or swim. It took all of two weeks to decide on a Pomagowski double chairlift. That summer slopes were cleared and groomed, the lift and warming house built, and the area opened in 1960, two years before Winter Park had its first chair lift. Dwight and Jean even had a fine neon sign at the entry off the highway, one more first. Saturday races, sponsored by Ski Idlewild and George/Hazel Ferris's Mountain Shop drew droves of youngsters. About 1961, Dwight introduced ski bicycles, which were hugely popular. He also started using the first snowmobile for grooming and first aid purposes in the area. In the meanwhile, Jean was identifying snowshoe and cross-country ski trails through the nearby back country. By 1964, their thoughts were turning to snowmaking, to enhance early skiing. To this day, people will walk up to the Millers and say, "Oh, Ski Idlewild! I learned to ski there! Loved it." As for summer activities, trips to areas of interest, swimming, and horseback rides were standbys. In addition, the Millers built a small golf course in the meadow and a trout pond at the bridge, which they stocked. As the Miller children grew, Dwight and Jean found that they wished for more family time together, and when an opportunity to sell the property came along in 1965, they gave up what was a flourishing, solid, and very profitable business, moving to Tabernash to try other challenges. Unfortunately, the new owner was not a good steward and Ski Idlewild gradually d clined. An era of exciting innovation came to an end.

|

- ‹ previous

- 6 of 7

- next ›