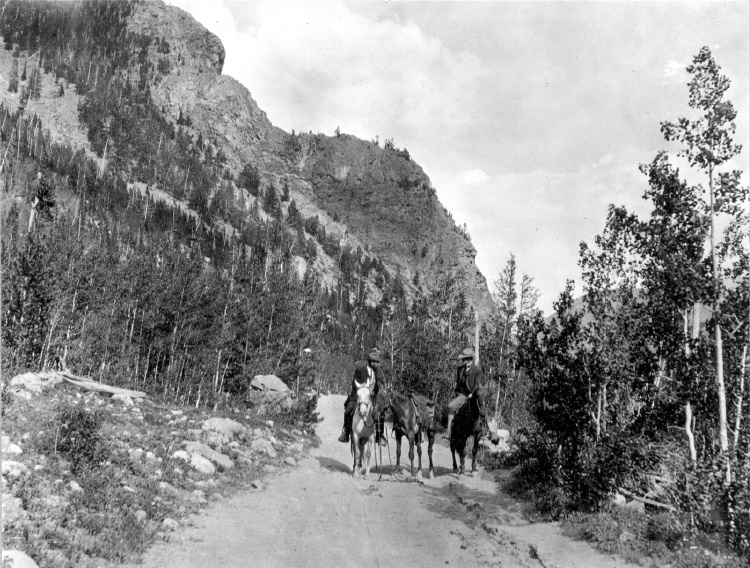

Dark clouds covered the Continental Divide as we looked east from the ridge leading toward Elk Mountain's remarkable view. Cool winds and spitting snow followed us. We weren't seeking the height of Elk Mountain, but instead, were tracking the historic path of Grand County Pioneer William Jefferson "Ute Bill" Thompson. Specifically, we wanted to locate the memorial marker for Ute Bill that Henry Grafke and Otto Schott placed along this ridge after Ute Bill died in 1926.

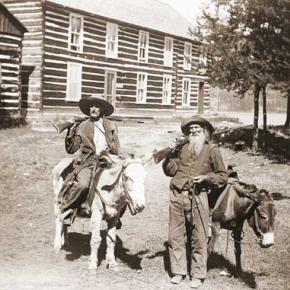

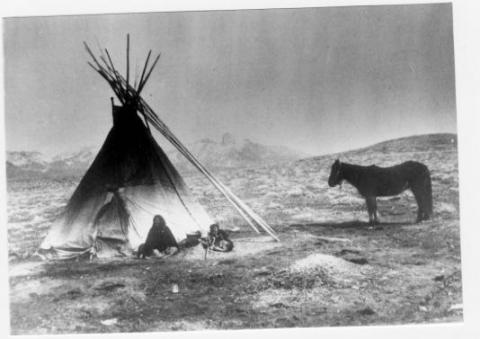

Tracking Thompson requires divergent paths. On one hand, Ute Bill's early presence in Middle Park places him in an era when mountain men and Ute Indians shared the vast herds of elk and deer. Only a handful of hardy souls called Middle Park home when Bill Thompson arrived in the late 1860s or early 70s. On another hand, Thompson settled just east of Hot Sulphur Springs as a young man, where he carved out a cattle ranch that remains in his family today.

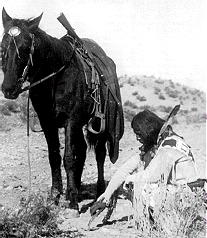

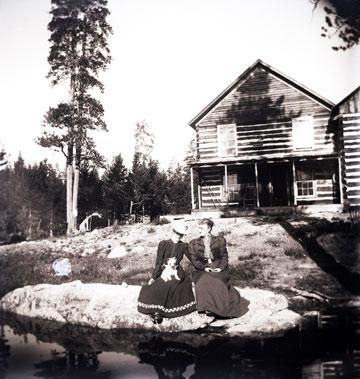

Records prove he owned and operated a billiard hall, drove stagecoaches and established a homestead along the Colorado (then, the Grand) River. But tall tales and oral legends abound too, capturing hair-breath escapes, harrowing western adventures and the mischievous nature of a 19th century westerner. Looking through the numerous historic photos of Ute Bill at the Pioneer Village Museum in Hot Sulphur Springs leaves an impression of a capable trapper, businessman and rancher who textured his image with stories of western adventure.

With Don Dailey - fellow historic trekker and great grandson of Ute Bill - along, I hoped to pursue the fact and folklore of Ute Bill. As Don pointed out an isolated cabin in the valley below, a Ute Bill tale from the Georgetown Arbitrator of September 1886, "as narrated at the time by one of the participants," captured my imagination.

Bill Thompson breathed a sigh of relief. The rugged, hungry band of Ute in front of him smiled approvingly as his long black hair fell from his broad-brimmed black hat. A tense moment before, he'd worried about his future as the small band of Ute Indians led by Yarmony came upon his isolated cabin in Middle Park. Fact is, Bill Thompson's hair had just saved his life. Not bein' cut since the Sioux captured him as a child, it hung nearly to his waist.

Bill was all set up for a Middle Park Winter, with supplies to last through the toughest stretch, when Yarmony and his band came along. Thompson cursed softly at himself for not payin' closer heed to their approach. "Figured they'd be out west by now," Bill muttered as he squared up to his guests.

Speakin' through a mix of hand signs, broken Ute and English that most fellers in the mountain parks west of the divide understood well enough for basic communication, Bill impressed the band with his manly firmness and calm self-confidence. Then Yarmony spoke, "Beescits," was all he said. Bill hesitated to open his cabin supplies. "Why, them folks are so hungry," he thought to himself, "they're near certain to go mad if they laid eyes on my bacon and flour." At best he'd be without supplies at a risky time of year. "No biscuits, fellers," Bill said with as much certainty as he could muster, "barely enough food fer myself. There's still a shaggy buffalo er two fer the takin' and every feller's got the same chance." When Bill finished talkin' he looked Yarmony square in the eyes. He watched the headman's leathered face swing toward his rough-sawn cabin door thoughtfully. "Beescits," he repeated.

Yarmony's band, snuggled in their elk skins and trade blankets, looked stoically at Bill. "Well," Bill said, throwing down his last ace, "seems you're intent on havin' my grub and I'm intent you ain't." Then, regrettin' it before he finished sayin' it, Bill raised the stakes, "Why don't we have us a shootin' contest fer it?" No immediate reaction caused Bill to wonder if he'd communicated clearly. Slowly, though, excitement spread through the crowd of Ute, as the entire band - from the pretty young girls to the big-bellies - looked to one feller. In front of Bill stepped a mountain-sized-Ute feller, creating a shadow as he approached. "Piah," the Ute whispered, breaking into a quiet chaos of conversations. Movin' quick and hopin' for some break, Bill scooped up his improved Winchester rifle as he threw off his broad-brimmed black hat so nothin' could obstruct his shootin' eye. Just as soon as his long black hair fell near his waist, the tense moment ended with a gasp from the Ute, followed by a welcome reception that meant more to Bill than any he recollected! Bill determined then and thar on never cuttin' his hair again!

As he eased down the gun smilin', all them pretty Ute girls began paintin' his face and braidin' his locks. Bill was feelin' positively giddy about his good fortune. Decidin' he just might owe these hungry Utes a favor fer endin' a potentially tragic shootin', he led 'em to a nearby ravine where he'd been watchin' a small herd of shaggy buffalo. Now Bill Thompson figured he'd repay 'em with meat, and still keep his own supplies. Leavin' the Ute on a rise above the ravine, he sauntered down to the fresh buffalo trail just as he heard the thunder of hooves around the ravine's bend to the south. Settlin' into a remote stand of lodge pole pines, he sat right along the path of the rumblin' bison. Pickin' out his choices as they rounded the bend, Bill's Winchester boomed repeatedly, each shot bringin' down a fat cow or a young bull.

Swaggering toward his kills, Bill was suddenly confronted by Sandy Mellon and Len Pollard, sneakin' along that ravine behind the buffalo. Not recognizin' Bill through all the paint and braids, Sandy thundered to Len that this Ute feller must "a stole Bill Thompon's gun," because there weren't many repeaters like his. Both their guns were trained on Bill. Calmly, Bill broke the silence. "Don't over-reach yourself, Sandy." Yes sir, Sandy knew from the voice that this-here Ute feller in front of him was really Bill Thompson. That day, he became Ute Bill.

Breathing hard to make the final incline, Don and I reached the point along the ridge of Elk Mountain where we expected to find the memorial. There it was, as we had hoped. After a hurrah for our success, we slowly read the plaque: "Hunting Grounds of "Ute Bill.'" As we snapped photos and drank water from our packs, I decided that where historic fact and local folklore meet, an authentic western tale begins.

,

,