May 8, 2010 Sky-Hi News

In January 1970, Gerald Groswold, then chairman of the board of Winter Park Ski Area, received a call from the Children's Hospital of Denver about program they'd been running at Arapahoe Basin for amputee children. A-Basin wasn't going to continue the program, and the hospital wanted to bring it to Winter Park.

In his morning meeting a few days later, George Engel, who ran Winter Park Ski School at the time, announced that this group was coming up in a week's time and asked for volunteers. Of the 40 or so ski instructors standing there that day, only one raised his hand to volunteer. Later, at lunch, Engel walked by the lone volunteer and threw a note in front of him. "Call this number. You're in charge," Engel said.

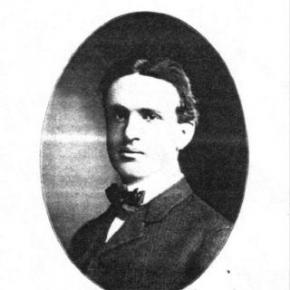

The 32-year-old Montreal-born ski instructor stared at the note while he finished eating his lunch. He had no way of knowing that by raising his hand he had just shifted the entire course his life as well as the lives of tens of thousands of others. That ski patroller was Hal O'Leary.

O'Leary went on to found the National Sports Center for the Disabled. Today, the NSCD is one of the largest outdoor therapeutic recreation agencies in the world. Each year, thousands of children and adults with disabilities take to the ski slopes, mountain trails and golf courses to learn more about sports, and themselves.

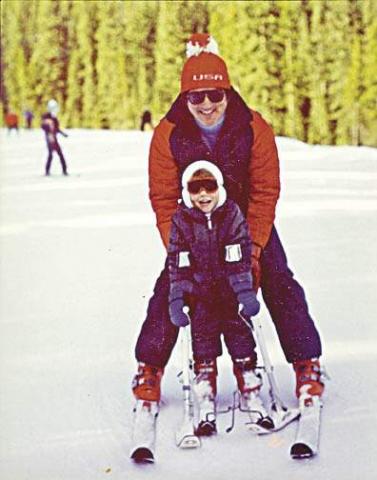

From the get-go, O'Leary had obstacles to overcome, starting with the fact that he'd never even known an amputee, not to mention seeing one ski. The day after he raised his hand, O'Leary got himself a set of outriggers and went about teaching himself to ski on one leg. Being schooled in the Professional Ski Instructions of America technique, he used all the same concepts as he would use for a conventional skier, sliding between turns.

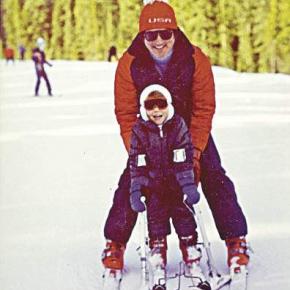

On Jan. 22, 1970, 23 amputee children arrived at Winter Park with equipment borrowed from Children's Hospital. It was a cold day, as O'Leary recalls, and he pushed the kids hard, making them climb up the bunny slope to turn around and practice making runs back down. Some of the kids who had participated in the program at A-Basin had been taught to jump turn the ski rather than sliding it. So they were hopping around like kangaroos, hopping three times to make each turn, O'Leary said. By 11 a.m., kids were collapsed on slope, crying. One screamed: "I hate your guts," O'Leary recalled.

Feeling that he had failed them, he took them over to the lift on Practice Slope after lunch and put them on the chairlift. A few bailed out, and O'Leary thought: ?Oh my God, I'm going to kill them,' he said: "I worried they'd end up in the tunnel." By the end of the day, however, the kids were flying down the hill, coats flapping in the wind and smiles on their faces. O'Leary was hooked.

For eight weeks the program continued. Before long, the television stations caught wind of what was going on at Winter Park. One day O'Leary got a call from the Today Show, which wanted to feature his program. No sooner had he hung up the phone then it rang again, and Good Morning America was on the line wanting an interview. "It really put Winter Park on the map in those days," he said. As word got out, people with different disabilities started calling O'Leary to set up lessons, from the visually impaired to the paraplegic.

For each new challenge a skier presented, O'Leary needed a new adaptation to the traditional ski equipment. He spent nights at the ski shop working on modifications and pouring over medical books. Improving the design of the outrigger was O'Leary's first challenge. O'Leary made a lot of phone calls back and forth with George Engel (who also owned Winter Park Ski Shop) and other product manufactures, explaining the design he needed, then they would build it.

Another early invention was the "ski bra." Originally made of metal, the contraption slid over the tip of the skis, holding them in place and preventing them from crossing. "The ski still had freedom, but it helped people that lack lateral control of their bodies," O'Leary said. Sit skis hadn't been invented either. So when a paraplegic wanted to ski, O'Leary modified a cross-country ski item out of Norway. "It reminded me of a little bathtub," he said. "It didn't have any runners. It made me nervous. But, people could use it in a seated position, and it got people who couldn't stand out on the hill."

One of the more peculiar adaptive designs that O'Leary saw over the years was a space suit worn by a paraplegic man. The man filled the suit with enough air that he could stand upright, which worked well, O'Leary said, until he sprang a leak and had to be rushed back down the hill. "In 40 years, it's amazing what has happened to the gear," O'Leary said.

If equipment is the backbone of the program, volunteers are its heart. "We couldn't do this without our volunteers," O'Leary said. More than 800 people volunteer every year with the NSCD. It's a dedicated group of people - the average volunteer has been involved with the program for more than eight years, O'Leary said. Just about anyone who can ski can volunteer. NSCD provides the training and, soon, the volunteers are teaching the lessons. Thanks to the volunteer program, a NSCD participant in 2010 can get a full day lesson with a private instructor, plus a lift ticket and adaptive equipment for $100. Scholarships help people who can't afford the price tag. Raising money to help offset costs and provide these scholarships is key for the program's success. The NSCD holds more than a dozen fund raisers each year, although the Wells Fargo Cup and the Hal O'Leary Golf Classic are two of the biggest and most well-known.

O'Leary built the adaptive skiing program for 10 years before it began to develop into something permanent. In the early years, he was challenged a lot by the ski area, he said. Lift ops had concern about people riding the chairs with different apparatus. The ski patrol was concerned about people with various abilities getting on slope. "There was opposition from different parts of the mountain," O'Leary said. But the program's champion - Gerry Groswold, who served as the ski area's president for 22 years, from 1974 to 1996 - held strong to his conviction that the mountain should make room for skiers of all abilities, O'Leary said.

While the majority of those other ski instructors - the ones that didn't raise their hands that day - moved on to other pursuits, O'Leary had found his life's purpose. "It was seeing smiles on people's faces," he said. "I never realized what it would mean, giving these people movement they did not have in a wheelchair or walking. It changed their life. It helped them in many ways with their challenges. They did better in school. They started focusing more. After several years, wanting to give back what they took, many of them became instructors themselves."

For the first four years, O'Leary still had to wait tables in the summer to survive. Finally, in 1974, O'Leary parted ways from Winter Park Ski School, and Winter Park Ski Area brought the disabled skier program under its wings with O'Leary at its helm. That year, O'Leary introduced summer activities to the program, including whitewater rafting and horseback riding. "That first summer went extremely well," he said. "The turnout was huge."

Today, the summer program has expanded to include almost any recreational activity imaginable, including rock climbing, biking, hiking, canoeing, kayaking, camping and fishing. Programs are designed for individuals, families and groups and are available for all levels of ability, from beginner to advanced. "What we offer now parallels what any tourist would want to do on a vacation in Colorado," O'Leary said.

O'Leary has spent the past 14 years traveling to other countries, lecturing, writing books and working with ski areas to set up programs and introduce adaptive equipment. "It's not easy to create a program at a ski area," he said. "Space is limited. You have to raise money to finance it. But the point is to create choices for people who have disabilities, choices like everyone else has."

In the United States, the sporting opportunities for disabled people have exploded in the past few decades, thanks, in large part to the early efforts of folks like O'Leary. Disabled Sports USA now recognizes 13 disabled sports programs in Colorado, far more than any other state. Although O'Leary, now 72, handed over the day-to-day operations of NSCD more than eight years ago, he still works daily. He's traveled to 13 different countries helping to create NSCD-style program. He's written the book, literally, on adaptive skiing techniques (Bold Tracks: Skiing for the Disabled).

Looking back on that January day 40 years ago when he innocently raised his hand, O'Leary said he'd do it all again: "I've gotten more out of it than I put into it," he said. "I've worked with fabulous people. I've had great opportunities. It's been a good life. It really has."